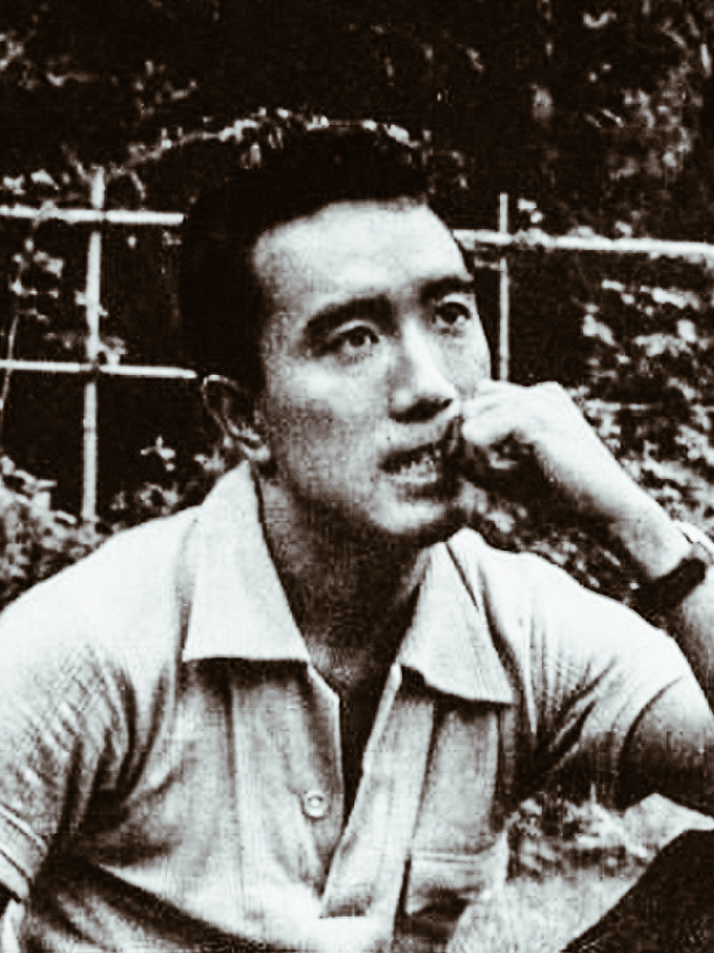

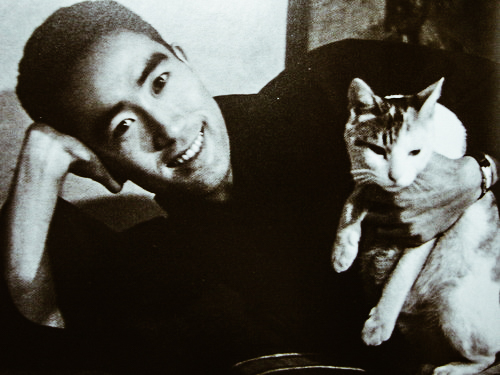

Yukio Mishima pseudonym of Kimitake Hiraoka (Tokyo, January 14, 1925 – Tokyo, November 25, 1970), was a Japanese writer, playwright, essayist and poet and this year marks the 50th anniversary of his death.

50 years since Yukio Mishima’s death

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: @williert

Mishima was a highly controversial character, considered close to Fascism in Europe and, according to many critics, a nostalgic Japanese nationalist. Alberto Moravia called him a decadent conservative. The two met in Mishima’s Art Nouveau western home in a suburb of Tokyo. Yukio Mishima, on the other hand, called himself apolitical and anti-political. Strongly patriotic, he also inspired numerous characters of his works, and the cult for the Emperor, seen as an abstract and/or semi-divine ideal, the embodiment of the essence of traditional Japan.

Kimitake Hiraoka was one of the few Japanese authors to have immediate success also abroad. His numerous works range from the real novel to the modernized and readapted forms of traditional Japanese theatre Kabuki and Nō. Yukio Mishima has revisited the Nō theatre in a modern key.

photo credits: thereaderwiki.com

The life of Yukio Mishima

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Yukio Mishima was born in Tokyo on January 14, 1925, in the home of his paternal grandparents, Jotarō Hiraoka and his wife Natsuko. Her parents, Azusa and Shizue, lived together with her grandparents and her grandmother who had an unhappy marriage, assumes all responsibility for the education of the child, usurping the role of the mother. It will be his grandmother to bring the child closer to classical literature and the forms of the theatre Nō and Kabuki.

The relationship that little Kimitake Hiraoka had with her grandmother was something very obsessive, even his mother was allowed to visit him only for breastfeeding.

photo credits: paola1chi.blogspot.com

Grandmother never allowed her grandson to leave the house until Hiraoka escaped from her grandmother stolen from her mother in 1934.

These and other experiences of childhood and adolescence are reported in the novel Confessions of a mask of 1949, in-depth self-analysis of his life.

From 1931 he began studying Gakushūin, the school of the Peers, always thanks to the advice of his grandmother. In this school, most of the students were part of the aristocracy. Those who were not aristocrats were called “outsiders”. With this school, students became more warriors than writers and Kimitake Hiraoka’s poems were published in the school magazine.

His first work, Hanazakari no Mori (The forest in bloom) was completed in 1941 and was heavily influenced by the Japanese romantic school (Nihon romanha). The professor of Gakushūin letters, Shimizu Fumio, immediately noticed his classical style. Bungei Bunka magazine published the story and from there he began to use the pseudonym Yukio Mishima. Hanazakari no Mori will be published in book form together with other short stories: its success will make the name of the writer known to the public for the first time.

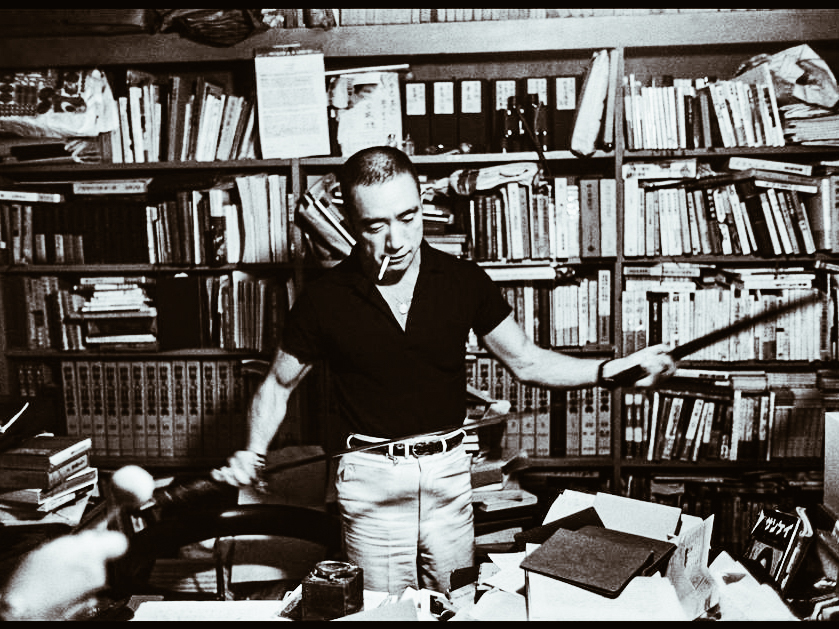

After school, convinced by his father, he enrolled in law university. After graduation, he won a competition as a state official at the Ministry of Finance. During the period of work at the Ministry, he lived a “double life”: state official until the evening and writer at night, sleeping no more than three or four hours.

photo credits: oltrelalinea.news

Early works

In 1946 he presented two of his works to the Nobel Prize winner Yasunari Kawabata. Between the two there was a feeling of profound esteem more than that which actually binds teacher and disciple.

In 1948 he began his work at the Kindai Bungaku magazine, linked to leftist circles. Yukio Mishima always tried to avoid any political argument in his novels, apart from the descriptive character that we find in After the feast and the Horses on the run, in fact, Yukio Mishima became part of the leftist group only to get more contacts with the intellectual world.

After the publication of Kamen no Kokuhaku (Confessions of a mask) in June 1949, he received recognition from critics and sales. Between 1950 and 1951 he published three important novels: Thirst for love, The Green Age (1950) and Forbidden Colors (1951). In the novel Thirst for the love he returns to the third-person narrative.

In 1951 he visited the United States, Brazil and Europe as a correspondent for Asahi Shinbun. In Shiosai (The voice of the waves 1954) and the trip to Greece marked the beginning of a new life for Mishima: from 1955 he began to devote himself to bodybuilding, and to kendo.

Yukio Mishima: marriage and sexuality

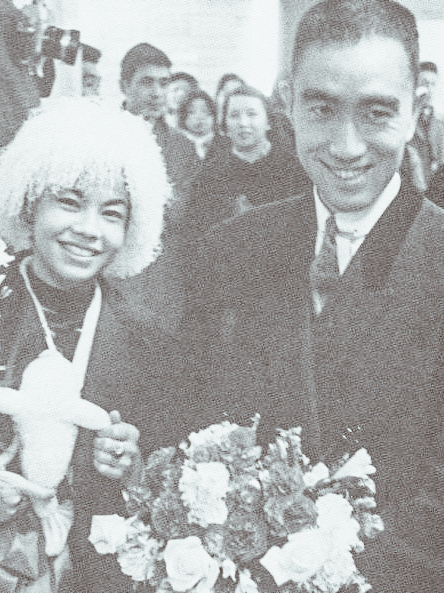

Yukio Mishima got married on 11 June 1958 with Yoko Sugiyama, under the advice of the family; two children were born from the union, Noriko (2 June 1959) and Ichiro (2 May 1962).

photo credits: paola1chi.blogspot.com

Yukio Mishima’s sexual orientation was highly controversial, due to some of his visits to Japanese gay bars. Many testimonies saw him as the protagonist of homosexual relationships with for example the writer Jiro Fukushima. The latter wrote a novel describing very explicit details of the relationship with Mishima. At that point, Mishima’s children started a fight for violating privacy.

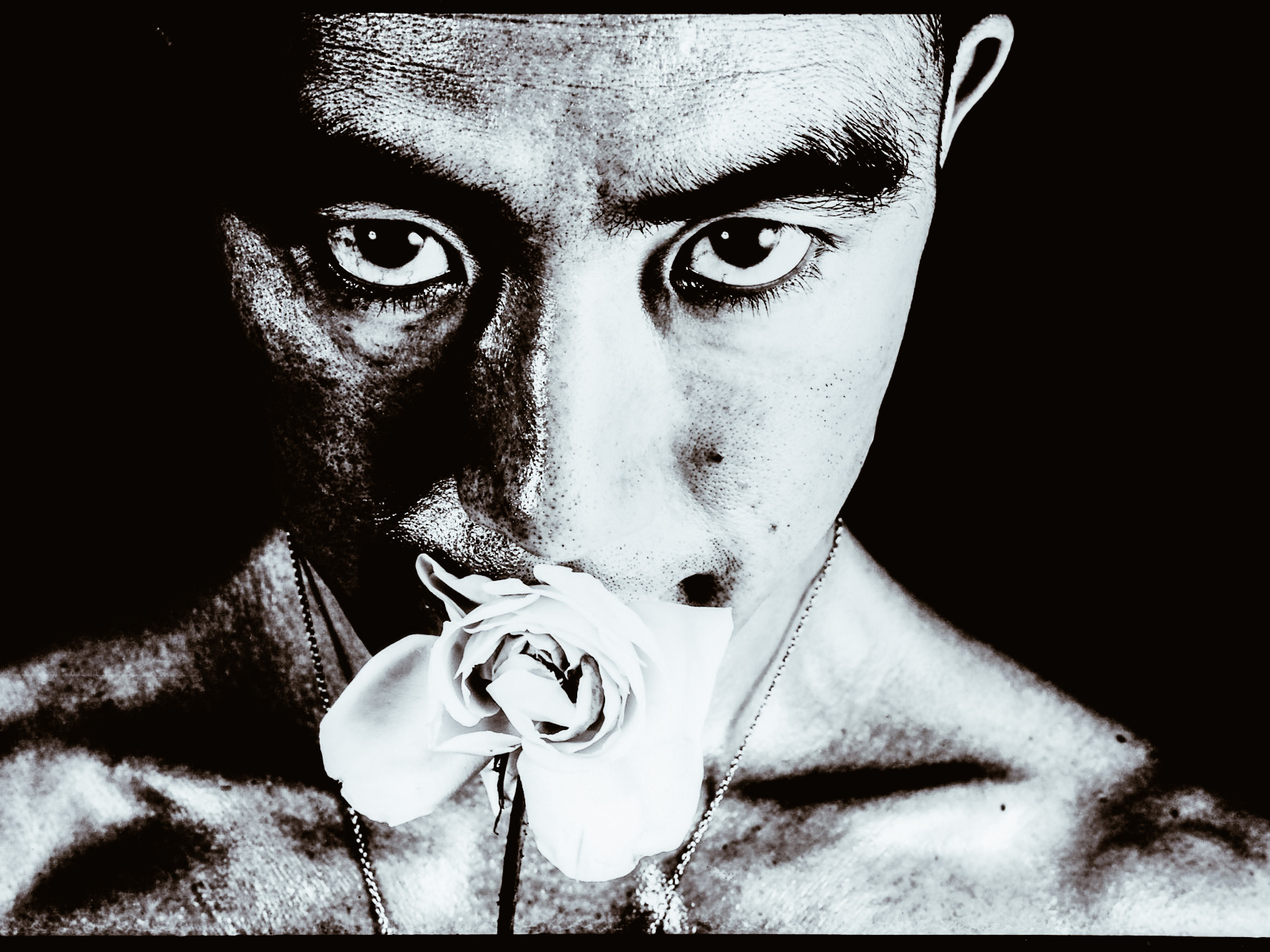

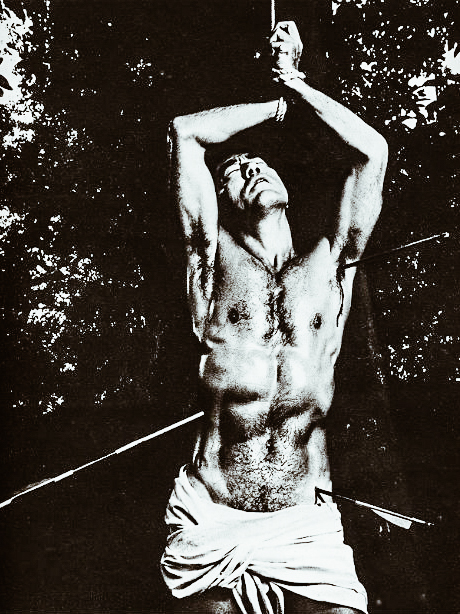

At that time Yukio Mishima entered into a relationship with Eikoh Hosoe and became the model for some of his photos of Bara-kei, 1961–1962. Abroad, the title will be Killed by Roses or Ordeal by Roses.

photo credits: dangerousminds.net

He began his acting career in the film based on Yūkoku (Patriotism, 1966), the story of a young officer who decides to do seppuku with his wife. The film was directed, written and played by him. In addition to this, his photos as a bodybuilder and kendōka are published in various newspapers, as well as news of the training periods together with the Jieitai (Japanese Self-Defense Force) and the foundation of the Tate no Kai (Shield Society), his “private army. ”

photo credits: lintellettualedissidente.it

The tetralogy Hōjō no Umi (The sea of fertility) began in 1965. The last volume is published in 1970.

Suicide

“A life that suffices to be face to face with death to be scarred and broken, perhaps it is nothing but a fragile glass.” (from Spiritual lessons for young samurai and other writings)

Yukio Mishima had always been obsessed with the idea of death and decided to combine this unease with the ideas of traditionalist patriotism.

On November 25, 1970, at 45, Yukio Mishima gathered the most important members of the Tate no Kai (“Association of Shields”), which he himself had found, and occupied the office of General Mashita of the self-defence army. From the balcony of the office, in front of a thousand men of the infantry regiment, as well as newspapers and televisions, he gave his last speech: exaltation of the spirit of Japan, condemnation of the 1947 constitution and the San Francisco treaty, which they made the Japanese national feeling enslaved by westernization.

«We must die to restore Japan’s true face! Is it good to have a life so dear to let the spirit die? What army is this that has no more noble values than life? Now we will testify to the existence of a higher value than attachment to life. This value is not freedom! It’s not a democracy! It’s Japan! It’s Japan, the country of history and traditions that we love. “It was November 25, 1970 in front of an audience of young soldiers, in which after this speech and after praising the Emperor, Yukio Mishima practised seppuku by piercing his belly and then having his head beheaded. Together with him, his most trusted friend and disciple, Masakatsu Morita, committed suicide too.

The choice of Seppuku

The date and manner of killing himself were not random, but chosen as the whole meaning of his life, the purpose for which it had been devoted. It all ended with the extreme act of the Japanese man: seppuku. This sacrifice was based on Wang Yangming’s Chinese teaching that “knowing and not acting means not knowing”.

Just before seppuku, he had delivered to the publisher the last part of the tetralogy The sea of fertility, which was however completed three months earlier, but with the date “November 25, 1970” just as a testament. He had organized his departure from the scene very coldly, he also left a note: “Human life is short, but I would like to live forever.”

The three survivors went to justice and were sentenced to four years in prison for occupying the ministry, but were released for good conduct after a few months.

Summarizing it all, we can say that according to Yukio Mishima the relationships between human beings are reduced to a cloudy and confused mixture of good and evil, of trust and diffidence, distilled in small doses. Despite all this, if the group of people manages to make a pact based on a purity of mind, consumerism, relativism, nihilism and individualism become nothing. Yukio Mishima managed to transform his existence into something more important and profound, thanks to the way he had decided to live and die.

photo credits: wikimedia.org

His works

Romances

The forest in bloom (花 ざ か り の 森 – Hanazakari no mori, 1944)

The doll’s house (雛 の 宿 – Hina no yado 1946-1963)

Confessions of a mask (仮 面 の 告白 – Kamen no kokuhaku, 1949)

Thirst for love (愛 の 渇 き – Ai no kawaki, 1950)

The Green Age (青 の 時代 – Ao no jidai, 1950)

Forbidden colours (禁 色 – Kinjiki, 1951)

Midsummer Death (真 夏 の 死 – Manatsu no shi, 1952)

The voice of the waves (潮 騒 – Shiosai, 1954)

A locked room (鍵 の か か る 部屋 – Kagi no kakaru heya, 1954)

Five modern Nō (近代 能 楽 集 – Kindai nōgaku shū, 1956)

The golden pavilion (金 閣 寺 – Kinkakuji, 1956)

A wavering virtue (美 徳 の よ ろ め き – Bitoku no yoromeki, 2007)

Kyōko’s house (鏡子 の 家 – Kyōko no Ie, 1959)

After the banquet (宴 の あ と – Utage no ato, 1960)

Animal’s playthings (獣 の 戯 れ – Kemono no tawamure, 1961)

Wonderful star (美 し い 星 – Utsukushii Hoshi, 1962)

The taste of glory (午後 の 曳 航 – Gogo no eiko, 1963)

The school of meat – Nikutai No Gakko, 1963

The sword (1963)

Music (音 楽 – Ongaku, 1965)

Madame de Sade (サ ド 侯爵夫人 – Sado kōshaku fujin, 1965)

The voice of heroic spirits (英 霊 霊 聲 – Eirei no koe, 1966)

Evening dress (夜 会 服 – Yakaifuku), (1966-1967)

My friend Hitler (わ が 友 ヒ ッ ト ラ ー – Waga Tomo Hittorā, 1968)

The sea of fertility (豊 饒 の 海 – Hōjō no umi), 1968-1970, tetralogy composed of:

Spring snow (春 の 雪 – Haru no yuki, 1968)

Horses on the run (奔馬 – Honba, 1969)

The temple of dawn (暁 の 寺 – Akatsuki no tera, 1970)

The mirror of deception (天人 五 衰 – Tennin gosui, 1970)

Middle Ages & The Palace of the Roaring Deer (Mishima, history and secret affairs) (Chūsei, 1945–46 + Rokumeikan 1956)

Essays

1967 – Apollo’s cup (ア ポ ロ の 杯 – Aporo no Sakazuki, 1967)

The way of the samurai (葉 隠 入門 – Hagakure nyūmon, 1967)

Sun and steel (太陽 と 鉄 – Taiyō to tetsu, 1970)

1988 – Spiritual lessons for young Samurai (若 き サ ム ラ イ の た め の 精神 講話 – Wakaki Samurai no tameno Seishin kowa, 1970): a collection of essays including the proclamation read by the author a few moments before the ritual suicide.

1997 – Letters 1945-1970 (川端康成 ・ 三島 由 紀 夫 往復 書簡 – Kawabata Yasunari ・ Mishima Yukio Ohfuku Shokan, 1997), SE (ISBN 88-7710-543-7): correspondence between Mishima and Yasunari Kawabata.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)