We continue our series of in-depth articles dedicated to the Japanese culture and today we talk about Sakura, the flower symbol of the Rising Sun. “The perfect flower is a rare thing. One could spend a lifetime looking for it, and it would not be a wasted life.”

Sakura 桜 Symbolic flower of Japan

Guest Author: Flavia

This is how Ken Watanabe began in a scene from the famous film ‘The Last Samurai’ (2003) as the rebel samurai Katsumoto, against the backdrop of a beautiful Japanese garden. How could we not remember this scene from the film which, despite some historical inaccuracies, is able to give us moments like this. Surrounded by splendid trees in bloom, Katsumoto-Watanabe is simply staging the prototype of Japanese aesthetic sensitivity towards nature. In this case, towards flowers. But here we are talking about one flower in particular… the cherry blossom, an undisputed object of age-old admiration: the Sakura (桜 – さくら).

We are all familiar with cherry blossoms: their beauty is obvious, admiring them a natural consequence. This, I would say, needs no explanation. We can, however, talk about the particular importance of this delicate little flower in Japan, so much so that it has become a “moral” symbol (the official one is the chrysanthemum).

The term ‘Sakura’ refers to both the flower and the tree – known as the ‘Japanese cherry tree’ – a type of cherry tree characteristic of the Far East. There are about a hundred varieties of Sakura in Japan, including the big cities. But the most common are the Yamazakura and especially the (Somei-) Yoshino, with its typical pale pink-white colour, which has been admired by the Japanese for hundreds of springs.

photo credits: japan.stripes.com

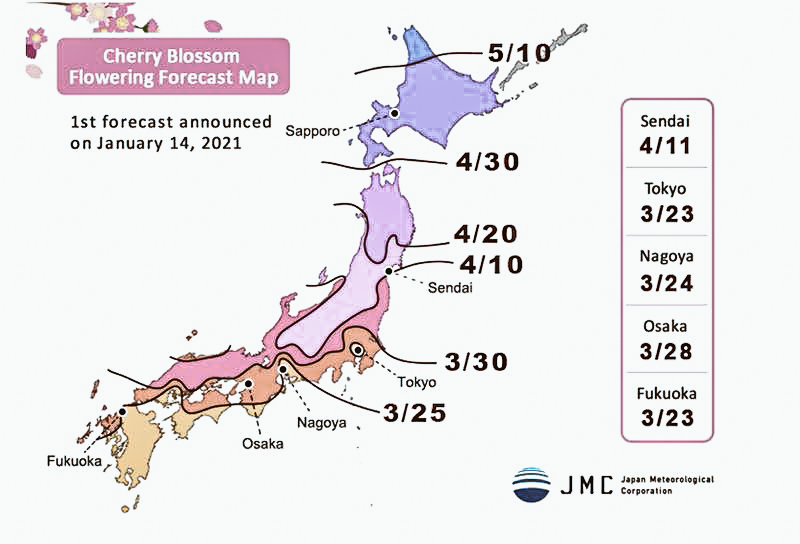

The Sakura is an institution in Japan, with its own special symbolism and deep meaning. It appears on the famous 100 yen coin and frames Fuji san, Japan’s other great symbol, on the back of the current 1000 yen note. It is so popular that the National Meteorological Agency issues a special Sakura Zensen ( 桜前線 ) bulletin every year to update on the status of the flowering. The media informs the population daily about the best spots, so that they can adjust for the beloved Hanami (flower-gazing) activity, deciding where and what variety of Sakura to see.

Flowering proceeds from south to north, as the climate is milder in southern areas. So if you arrive in Japan when the flowering has already passed in the centre-south, look at the calendar, you might still be in time to catch them in Hokkaidō!

Mankai 🌸 Flowering

The average flowering time varies according to geographical location, but in any case it is short: a few days, maximum ten days. It starts in Okinawa, around the end of January, gradually moving northwards with the last buds opening around mid-May in Hokkaidō. This is the approximate time period. Bad weather, disturbances or sudden changes in temperature can obviously affect the duration of flowering, given the extreme delicacy of the little flower. It all depends on the climate and the year: it can happen that the flowers bloom a little earlier or later, or that the blooming is interrupted by a sudden change in climate. The time of the flowering boom is known as Mankai (満開), which in fact means ‘full opening’.

photo credits: japan.stripes.com

As mentioned above, most cherry trees are of the Somei-Yoshino variety, but there are over a hundred species. Some are even capable of producing edible fruit. Of the criteria for distinguishing between the different types, the most immediate is undoubtedly the number of petals, which can be ten, twenty or even more. The most common are the classic five-petalled Sakura, both wild and cultivated.

🌸 Types of Sakura

But let’s look at some examples of more unusual cherry trees. In addition to Somei-Yoshino, the most cultivated and popular, we can find:

- Yama-zakura (山桜), the ‘Mountain Cherry’. Very popular, it ranks right after Somei-Yoshino in terms of popularity. It has large pink buds and five petals.

- Fuyu-zakura (冬桜), or “Winter Sakura”. As the name suggests, it is a cherry tree that begins to blossom in autumn and continues in winter, although not continuously.

- Yae-zakura (八重桜), the “Double Cherry Tree”. So called because of its ‘reinforced’, i.e. very full-bodied, bud with more than five petals. It is associated with the ancient capital Nara (奈良).

- Shidare-zakura (枝垂桜), i.e. “weeping cherry tree” because its branches fall, like a willow, creating a cascade of pink flowers. It is the official flower of the Kyoto prefecture.

- Ichiyō (一葉), “a leaf”. It owes its name to a leaf-like pistil that emerges from its centre when fully open. It is one of those that can have 20 to 40 petals.

photo credits: Akemi K on Flickr, medigaku.com, Pinterest

Ippon-zakura (一本桜) are defined as all cherry trees planted “in solitude”. These include Japan’s three great cherry trees, the Sandai-zakura (三大桜). The trio consists of the Jindai-zakura in Yamanashi, the Usuzumi-zakura in Gifu and the Takizakura in Fukushima. Jindai and Usuzumi belong to the Edohigan variety (from which Yoshino is also derived), while Takizakura is a weeping cherry tree. In particular, the Jindai-zakura, located in the Jissōji temple (實相寺), is perhaps the oldest in Japan: it is about two thousand years old and has a circumference of 13 and a half metres!

Spring (春), season of hope

The act of contemplating trees in blossom dates back to the Nara period (8th century). Initially the prerogative of the imperial court of Kyoto, over the centuries it was extended first to the category of samurai and then to the rest of the population. Let us say that in the beginning it was the plum tree (梅-Ume) that was the object of attention. The plum tree represented the link with China, as it originated there. But already in the Heian period (8th-12th centuries), due to the interruption of relations with Middle Earth, the Ume was ousted by the more autochthonous Sakura. From then on, spring-themed poems began to refer to Sakura even only as “flowers” (花-Hana) and the word “Hanami” also became interchangeable with “sakura”. Linguistic details, however, are indicative.

Spring (春- Haru) has always been characterised as a symbol of rebirth, of generating power.

In ancient times, the blossoming of cherry trees was associated with prosperity, as it presaged an abundant rice harvest. In order to propitiate a good harvest the following year, the beginning of the planting season was opened with a series of rituals ending with joyful celebrations under the Sakura. In the 18th century, Shōgun Yoshimune Tokugawa further promoted this custom by planting Sakura trees in various areas.

Today, spring is the season for students, graduates and undergraduates, who rely on the auspiciousness of the blossom. April marks the start of the new school year for students, while graduates and many school leavers are preparing to enter the world of work. April also marks the start of the new fiscal year in Japan. In short, the cherry blossom season brings with it some beginnings in that land. Therefore, it is duly celebrated with the Sakura Matsuri (桜祭り) festival.

photo credits: Pinterest, Pinterest

Sakura in sweets and delicacies

Sakura and spring are also celebrated through food, in keeping with good Japanese tradition. Famous is the Hanami Bentō (花見弁当), or the bentō that is a must during a picnic under the cherry blossoms. For those who don’t know, the bentō is a box for a picnic lunch, used by the Japanese all year round, but in this period it has a Sakura theme. You might find Sakura Onigiri (桜おにぎり) in there, for example, rice balls with salted Sakura on top.

However, there is also cherry blossom tea (桜茶, Sakura-cha), possibly combined with Sakura-Mochi (桜餅), a typical rice cake with red bean paste, wrapped in a salted cherry leaf. Sakura infusion is offered to newlyweds on their wedding day as it is considered a good omen. Wagashi (和菓子) – the traditional Japanese confectionery – come in a variety of sakura-themed varieties. Again, among the more commercial products: just as you can have Matcha-milk, there is also an all-pink Sakura-milk. And we could go on and on, but perhaps we’d better stop, otherwise our mouths will water too much!

photo credits: kitchenbook.jp, pinterest.fr

Hanami (花見), admire the buds

Hanafubuki (花吹雪): “snowy storm of buds”. This is how the spectacle of falling petals from cherry trees in bloom is defined, whose rain colours the landscape in a kind of “spring snowfall”. If one of these petals (花びら- Hanabira) falls into one’s sake glass while making Hanami, it is a propitiatory sign of good health.

As mentioned at the beginning, the word “Hanami” means the practice of looking at cherry blossoms (花= flower(s), 見= watching). Nowadays, Hanami celebrations can range from simple picnics to more elaborate celebrations with music and entertainment. They can also take place at night, in which case, we talk about Yozakura (夜桜) or “sakura by night”. The result, you can imagine: an evocative nocturnal Hanami, amid paper lanterns and moonlight.

photo credits: power-shower.com

However, the peculiarity of Hanami is not in simply witnessing this spectacle of nature: it is in assisting it by capturing its fleeting appearance. The beauty of the buds also lies in their transience. In those who contemplate them, a feeling of sweet melancholy arises… which the delicacy of these flowers is able to evoke when, having detached themselves from the tree, they float carried by the wind or a delicate breeze, to then settle on the ground. An emotion given by the realisation that this is nothing other than the ultimate nature of human existence itself: destined, sooner or later, to have an end.

“So I come to this place with my ancestors and a thought comes back to me: like these sprouts we are all dying… recognising life in every breath, in every cup of tea, in every life we take away… ” [ Katsumoto Moristugu – The Last Samurai ]

photo credits: YouTube

Symbolism of Sakura: mono no aware (物の哀れ)

The symbolism of Sakura is therefore both sweet and bitter, but this should not surprise us, as we are familiar with the Japanese feeling of “Mono no aware”. In other words, a “pathos for things” characterised by a delicate hint of nostalgia, due to the awareness of their constant change. A concept that our Sakura embodies to perfection and of which he inevitably becomes the spokesman. Its beauty is enchanting but evanescent, ephemeral. So contemplation becomes sweet because of the delicacy of the flower, but also melancholic… because it is aware of its evanescence. Thus we contemplate its splendour but with an aftertaste of sadness. In a few words, this is the essence of Sakura.

Once again we are faced with an aesthetic that transcends the exterior. An exterior whose beauty hooks individuals, then leads them to a wider form of contemplation. We have seen this well, also in our article dedicated to Wabi-Sabi 侘寂. This has never been more true than in the case of the Sakura.

Cherry blossoms thus symbolise the transience of life and cyclicity. Because they blossom in all their glory, but their show remains for a limited time. The transience of life, youth and beauty: a metaphor that nature itself seems to want to offer every year and which Japan has been particularly careful to capture. At the same time, however, they are also a symbol of (re)birth and hope… because every year they come back to bloom in all their splendour.

Wonderful and a symbol of vitality on the one hand, extremely fragile on the other: this is their dual nature. Given this awareness, the reference to Buddhism is inevitable.

Symbolism of Sakura: other meanings

Other more specific meanings attributed to Sakura have to do with the number 5. So, naturally, it is the classic five-petalled cherry tree that best lends itself to this type of symbolism. The number 5 is said to recall the Japanese cosmogonic myth (about the birth of the ‘cosmos’), according to which there were originally two gods, Izanagi and Izanami, who fathered five children; the birth of the fifth child, the god of fire, would prove fatal to the mother-goddess Izanami. Izanagi, distraught, thus killed this son, from whose parts the mountain gods would then originate. The number 5 also refers to the Japanese esoteric Buddhist concept of the five orientations (cardinal points plus the centre) and the five elements of water, fire, earth, ether and vacuum.

More generally, cherry trees can also be associated with clouds simply because of a visual issue: their mass blossoming can be reminiscent of clouds in the sky. A bit like the expression ‘Hanafubuki’ we saw earlier, where fubuki (吹雪) alone means ‘snowstorm’.

photo credits: Flavia

As the Sakura, so the Samurai

But back to our Katsumoto-Watanabe, his sentence actually ended with “…this is Bushidō”. In fact, Sakura was also associated with the ideal of the way of the warrior and the figure of the samurai (侍), so much so that it became the emblem of the category. You will say, where is the similarity? In the fact that the cherry blossom embodied the qualities typically associated with the samurai (courage, purity, honesty, loyalty…). As the Sakura dies at the height of its splendour, so the samurai at the height of his vitality and strength was ready to die if the time came. In this sense, his life, however grand, was as fragile as that of a cherry blossom. However, he was not afraid of death, since it was experienced as a last ideal act and the only possible honourable end, in the name of extreme loyalty to his values.

In the cherry tree, the bushi (warrior) found his model and identified his life with it. Just like the delicate little flower, he had to lead his existence giving his all, through dedication in every gesture, until his last sigh. All that mattered was to “burn” as much as possible through that fuel, which was his life force. In all this, there could be no room for the fear of death. On the contrary, it was in the warrior’s last moments that his beauty shone brightest.

So the Sakura, so the bushi: just like in the proverb “Hana wa sakura-gi, hito wa bushi” ( 花は桜木-人は武士 ) that is “Among the flowers the cherry tree, among the people the warrior”. The samurai in battle could fall under the blows of the opponent, just like buds that fall to the ground detached from the branches by a gust of wind or rain. Just like so many small, triumphant buds, the samurai flourished, only to meet their fate.

photo credits: Pinterest

This identification was also used in various ways by Imperial Japan centuries later. Among others: the Sakura was reproduced on the sides and in the name itself of the Ōka ( 桜花 ) airplanes to symbolise the extreme act of the Tokkōtai (Special Attack Unit) Kamikaze at the end of World War II. The pilots themselves, on the verge of their suicide mission, are said to have embarked carrying a cherry branch.

Nowadays, the Sakura may symbolise the martial arts.

“Woman sitting under the cherry blossom trees”

photo credits: appareassociazione.blogspot.com

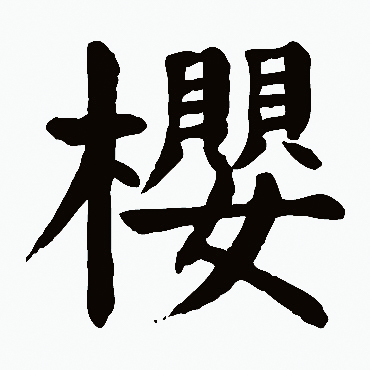

This is the image that could be drawn – certainly the one I see – by observing the ideogram of “sakura”. This is far from being the explanation why the kanji 桜 has this specific form, but it lends itself well to such an interpretation. Especially given its present simplified form. Before leaving us, we cannot conclude without a parenthesis on the writing and the cherry tree kanji.

As you can see in the picture above, Sakura’s ideogram 桜 is composed on the left of the radical 木 (=tree), on the right of three dashes with the character 女 (=woman) below. The little part in pink, tell the truth: doesn’t it really resemble the petals of a flower?

Actually, this part used to be written in a more elaborate way and had nothing to do with the meaning. It was written like this: 櫻. Later on, it underwent a process of simplification, like so many other ideograms in both Japan and China (where they come from). Bearing in mind that ideograms derive from pictograms, let us observe our character in its transition from pictogram to ideogram in the images below.

photo credits: shufam.hao86.com, shufa.m.supfree.net

This was its transition, and then in more modern times it changed exactly as follows: 櫻 🡪 桜 (in China it became 🡪 樱 ). The double 貝貝, which preceded the present three hyphens, indicated “necklace”; while the single 貝 still means “shell”. So you see how, by investigating the Chinese etymology, the real historical evolution is revealed. Be careful, however, because the whole right-hand side (i.e. 嬰) of the ideogram 櫻 has reason to be there solely for a phonetic reason. (Not for reasons of meaning, which is also different between Chinese and Japanese). That is, that part has been “put” there to give the pronunciation to the kanji 櫻 as a whole.

But beyond this brief digression, we still like to see it like this: like a little woman under a flowering tree. Right? Since we are dealing with the simplified character today, we can safely indulge in this reading of the kanji which, coincidentally, is very reminiscent of the image of a woman under the blossoming cherry trees. And it certainly helps a lot to remember the ideogram. After all, this flower also recalls femininity. It is no coincidence that Sakura, or the variant Sakurako (桜子or 櫻子), are quite common female names in Japan.

photo credits: pinterest.it

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)