Sakura, an in-depth look at the flower symbol of Japan

We continue our series of in-depth articles dedicated to the Japanese culture and today we talk about Sakura, the flower symbol of the Rising Sun. "The perfect flower is a rare thing. One could spend a lifetime looking for it, and it would not be a wasted life."

Sakura 桜 Symbolic flower of Japan

Guest Author: Flavia

This is how Ken Watanabe began in a scene from the famous film 'The Last Samurai' (2003) as the rebel samurai Katsumoto, against the backdrop of a beautiful Japanese garden. How could we not remember this scene from the film which, despite some historical inaccuracies, is able to give us moments like this. Surrounded by splendid trees in bloom, Katsumoto-Watanabe is simply staging the prototype of Japanese aesthetic sensitivity towards nature. In this case, towards flowers. But here we are talking about one flower in particular... the cherry blossom, an undisputed object of age-old admiration: the Sakura (桜 - さくら).

We are all familiar with cherry blossoms: their beauty is obvious, admiring them a natural consequence. This, I would say, needs no explanation. We can, however, talk about the particular importance of this delicate little flower in Japan, so much so that it has become a "moral" symbol (the official one is the chrysanthemum).

The term 'Sakura' refers to both the flower and the tree - known as the 'Japanese cherry tree' - a type of cherry tree characteristic of the Far East. There are about a hundred varieties of Sakura in Japan, including the big cities. But the most common are the Yamazakura and especially the (Somei-) Yoshino, with its typical pale pink-white colour, which has been admired by the Japanese for hundreds of springs.

photo credits: japan.stripes.com

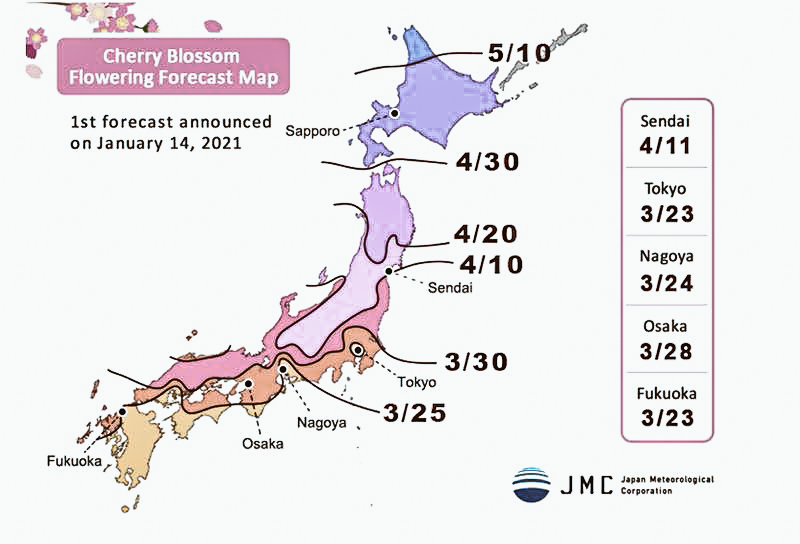

The Sakura is an institution in Japan, with its own special symbolism and deep meaning. It appears on the famous 100 yen coin and frames Fuji san, Japan's other great symbol, on the back of the current 1000 yen note. It is so popular that the National Meteorological Agency issues a special Sakura Zensen ( 桜前線 ) bulletin every year to update on the status of the flowering. The media informs the population daily about the best spots, so that they can adjust for the beloved Hanami (flower-gazing) activity, deciding where and what variety of Sakura to see.

Flowering proceeds from south to north, as the climate is milder in southern areas. So if you arrive in Japan when the flowering has already passed in the centre-south, look at the calendar, you might still be in time to catch them in Hokkaidō!

Mankai 🌸 Flowering

The average flowering time varies according to geographical location, but in any case it is short: a few days, maximum ten days. It starts in Okinawa, around the end of January, gradually moving northwards with the last buds opening around mid-May in Hokkaidō. This is the approximate time period. Bad weather, disturbances or sudden changes in temperature can obviously affect the duration of flowering, given the extreme delicacy of the little flower. It all depends on the climate and the year: it can happen that the flowers bloom a little earlier or later, or that the blooming is interrupted by a sudden change in climate. The time of the flowering boom is known as Mankai (満開), which in fact means 'full opening'.

photo credits: japan.stripes.com

As mentioned above, most cherry trees are of the Somei-Yoshino variety, but there are over a hundred species. Some are even capable of producing edible fruit. Of the criteria for distinguishing between the different types, the most immediate is undoubtedly the number of petals, which can be ten, twenty or even more. The most common are the classic five-petalled Sakura, both wild and cultivated.

🌸 Types of Sakura

But let's look at some examples of more unusual cherry trees. In addition to Somei-Yoshino, the most cultivated and popular, we can find:

- Yama-zakura (山桜), the 'Mountain Cherry'. Very popular, it ranks right after Somei-Yoshino in terms of popularity. It has large pink buds and five petals.

- Fuyu-zakura (冬桜), or "Winter Sakura". As the name suggests, it is a cherry tree that begins to blossom in autumn and continues in winter, although not continuously.

- Yae-zakura (八重桜), the "Double Cherry Tree". So called because of its 'reinforced', i.e. very full-bodied, bud with more than five petals. It is associated with the ancient capital Nara (奈良).

- Shidare-zakura (枝垂桜), i.e. "weeping cherry tree" because its branches fall, like a willow, creating a cascade of pink flowers. It is the official flower of the Kyoto prefecture.

- Ichiyō (一葉), "a leaf". It owes its name to a leaf-like pistil that emerges from its centre when fully open. It is one of those that can have 20 to 40 petals.

photo credits: Akemi K on Flickr, medigaku.com, Pinterest

Ippon-zakura (一本桜) are defined as all cherry trees planted "in solitude". These include Japan's three great cherry trees, the Sandai-zakura (三大桜). The trio consists of the Jindai-zakura in Yamanashi, the Usuzumi-zakura in Gifu and the Takizakura in Fukushima. Jindai and Usuzumi belong to the Edohigan variety (from which Yoshino is also derived), while Takizakura is a weeping cherry tree. In particular, the Jindai-zakura, located in the Jissōji temple (實相寺), is perhaps the oldest in Japan: it is about two thousand years old and has a circumference of 13 and a half metres!

Spring (春), season of hope

The act of contemplating trees in blossom dates back to the Nara period (8th century). Initially the prerogative of the imperial court of Kyoto, over the centuries it was extended first to the category of samurai and then to the rest of the population. Let us say that in the beginning it was the plum tree (梅-Ume) that was the object of attention. The plum tree represented the link with China, as it originated there. But already in the Heian period (8th-12th centuries), due to the interruption of relations with Middle Earth, the Ume was ousted by the more autochthonous Sakura. From then on, spring-themed poems began to refer to Sakura even only as "flowers" (花-Hana) and the word "Hanami" also became interchangeable with "sakura". Linguistic details, however, are indicative.

Spring (春- Haru) has always been characterised as a symbol of rebirth, of generating power.

In ancient times, the blossoming of cherry trees was associated with prosperity, as it presaged an abundant rice harvest. In order to propitiate a good harvest the following year, the beginning of the planting season was opened with a series of rituals ending with joyful celebrations under the Sakura. In the 18th century, Shōgun Yoshimune Tokugawa further promoted this custom by planting Sakura trees in various areas.

Today, spring is the season for students, graduates and undergraduates, who rely on the auspiciousness of the blossom. April marks the start of the new school year for students, while graduates and many school leavers are preparing to enter the world of work. April also marks the start of the new fiscal year in Japan. In short, the cherry blossom season brings with it some beginnings in that land. Therefore, it is duly celebrated with the Sakura Matsuri (桜祭り) festival.

photo credits: Pinterest, Pinterest

Sakura in sweets and delicacies

Sakura and spring are also celebrated through food, in keeping with good Japanese tradition. Famous is the Hanami Bentō (花見弁当), or the bentō that is a must during a picnic under the cherry blossoms. For those who don't know, the bentō is a box for a picnic lunch, used by the Japanese all year round, but in this period it has a Sakura theme. You might find Sakura Onigiri (桜おにぎり) in there, for example, rice balls with salted Sakura on top.

However, there is also cherry blossom tea (桜茶, Sakura-cha), possibly combined with Sakura-Mochi (桜餅), a typical rice cake with red bean paste, wrapped in a salted cherry leaf. Sakura infusion is offered to newlyweds on their wedding day as it is considered a good omen. Wagashi (和菓子) - the traditional Japanese confectionery - come in a variety of sakura-themed varieties. Again, among the more commercial products: just as you can have Matcha-milk, there is also an all-pink Sakura-milk. And we could go on and on, but perhaps we'd better stop, otherwise our mouths will water too much!

photo credits: kitchenbook.jp, pinterest.fr

Hanami (花見), admire the buds

Hanafubuki (花吹雪): "snowy storm of buds". This is how the spectacle of falling petals from cherry trees in bloom is defined, whose rain colours the landscape in a kind of "spring snowfall". If one of these petals (花びら- Hanabira) falls into one's sake glass while making Hanami, it is a propitiatory sign of good health.

As mentioned at the beginning, the word "Hanami" means the practice of looking at cherry blossoms (花= flower(s), 見= watching). Nowadays, Hanami celebrations can range from simple picnics to more elaborate celebrations with music and entertainment. They can also take place at night, in which case, we talk about Yozakura (夜桜) or "sakura by night". The result, you can imagine: an evocative nocturnal Hanami, amid paper lanterns and moonlight.

photo credits: power-shower.com

However, the peculiarity of Hanami is not in simply witnessing this spectacle of nature: it is in assisting it by capturing its fleeting appearance. The beauty of the buds also lies in their transience. In those who contemplate them, a feeling of sweet melancholy arises... which the delicacy of these flowers is able to evoke when, having detached themselves from the tree, they float carried by the wind or a delicate breeze, to then settle on the ground. An emotion given by the realisation that this is nothing other than the ultimate nature of human existence itself: destined, sooner or later, to have an end.

"So I come to this place with my ancestors and a thought comes back to me: like these sprouts we are all dying... recognising life in every breath, in every cup of tea, in every life we take away... " [ Katsumoto Moristugu - The Last Samurai ]

photo credits: YouTube

Symbolism of Sakura: mono no aware (物の哀れ)

The symbolism of Sakura is therefore both sweet and bitter, but this should not surprise us, as we are familiar with the Japanese feeling of "Mono no aware". In other words, a "pathos for things" characterised by a delicate hint of nostalgia, due to the awareness of their constant change. A concept that our Sakura embodies to perfection and of which he inevitably becomes the spokesman. Its beauty is enchanting but evanescent, ephemeral. So contemplation becomes sweet because of the delicacy of the flower, but also melancholic... because it is aware of its evanescence. Thus we contemplate its splendour but with an aftertaste of sadness. In a few words, this is the essence of Sakura.

Once again we are faced with an aesthetic that transcends the exterior. An exterior whose beauty hooks individuals, then leads them to a wider form of contemplation. We have seen this well, also in our article dedicated to Wabi-Sabi 侘寂. This has never been more true than in the case of the Sakura.

Cherry blossoms thus symbolise the transience of life and cyclicity. Because they blossom in all their glory, but their show remains for a limited time. The transience of life, youth and beauty: a metaphor that nature itself seems to want to offer every year and which Japan has been particularly careful to capture. At the same time, however, they are also a symbol of (re)birth and hope... because every year they come back to bloom in all their splendour.

Wonderful and a symbol of vitality on the one hand, extremely fragile on the other: this is their dual nature. Given this awareness, the reference to Buddhism is inevitable.

Symbolism of Sakura: other meanings

Other more specific meanings attributed to Sakura have to do with the number 5. So, naturally, it is the classic five-petalled cherry tree that best lends itself to this type of symbolism. The number 5 is said to recall the Japanese cosmogonic myth (about the birth of the 'cosmos'), according to which there were originally two gods, Izanagi and Izanami, who fathered five children; the birth of the fifth child, the god of fire, would prove fatal to the mother-goddess Izanami. Izanagi, distraught, thus killed this son, from whose parts the mountain gods would then originate. The number 5 also refers to the Japanese esoteric Buddhist concept of the five orientations (cardinal points plus the centre) and the five elements of water, fire, earth, ether and vacuum.

More generally, cherry trees can also be associated with clouds simply because of a visual issue: their mass blossoming can be reminiscent of clouds in the sky. A bit like the expression 'Hanafubuki' we saw earlier, where fubuki (吹雪) alone means 'snowstorm'.

photo credits: Flavia

As the Sakura, so the Samurai

But back to our Katsumoto-Watanabe, his sentence actually ended with "...this is Bushidō". In fact, Sakura was also associated with the ideal of the way of the warrior and the figure of the samurai (侍), so much so that it became the emblem of the category. You will say, where is the similarity? In the fact that the cherry blossom embodied the qualities typically associated with the samurai (courage, purity, honesty, loyalty...). As the Sakura dies at the height of its splendour, so the samurai at the height of his vitality and strength was ready to die if the time came. In this sense, his life, however grand, was as fragile as that of a cherry blossom. However, he was not afraid of death, since it was experienced as a last ideal act and the only possible honourable end, in the name of extreme loyalty to his values.

In the cherry tree, the bushi (warrior) found his model and identified his life with it. Just like the delicate little flower, he had to lead his existence giving his all, through dedication in every gesture, until his last sigh. All that mattered was to "burn" as much as possible through that fuel, which was his life force. In all this, there could be no room for the fear of death. On the contrary, it was in the warrior's last moments that his beauty shone brightest.

So the Sakura, so the bushi: just like in the proverb "Hana wa sakura-gi, hito wa bushi" ( 花は桜木-人は武士 ) that is "Among the flowers the cherry tree, among the people the warrior". The samurai in battle could fall under the blows of the opponent, just like buds that fall to the ground detached from the branches by a gust of wind or rain. Just like so many small, triumphant buds, the samurai flourished, only to meet their fate.

photo credits: Pinterest

This identification was also used in various ways by Imperial Japan centuries later. Among others: the Sakura was reproduced on the sides and in the name itself of the Ōka ( 桜花 ) airplanes to symbolise the extreme act of the Tokkōtai (Special Attack Unit) Kamikaze at the end of World War II. The pilots themselves, on the verge of their suicide mission, are said to have embarked carrying a cherry branch.

Nowadays, the Sakura may symbolise the martial arts.

"Woman sitting under the cherry blossom trees"

photo credits: appareassociazione.blogspot.com

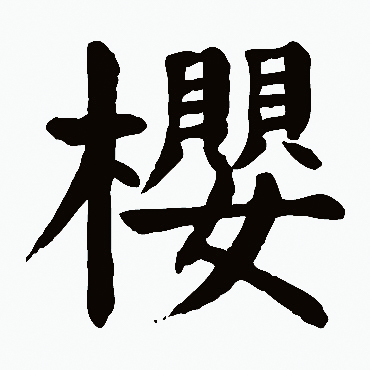

This is the image that could be drawn - certainly the one I see - by observing the ideogram of "sakura". This is far from being the explanation why the kanji 桜 has this specific form, but it lends itself well to such an interpretation. Especially given its present simplified form. Before leaving us, we cannot conclude without a parenthesis on the writing and the cherry tree kanji.

As you can see in the picture above, Sakura's ideogram 桜 is composed on the left of the radical 木 (=tree), on the right of three dashes with the character 女 (=woman) below. The little part in pink, tell the truth: doesn't it really resemble the petals of a flower?

Actually, this part used to be written in a more elaborate way and had nothing to do with the meaning. It was written like this: 櫻. Later on, it underwent a process of simplification, like so many other ideograms in both Japan and China (where they come from). Bearing in mind that ideograms derive from pictograms, let us observe our character in its transition from pictogram to ideogram in the images below.

photo credits: shufam.hao86.com, shufa.m.supfree.net

This was its transition, and then in more modern times it changed exactly as follows: 櫻 🡪 桜 (in China it became 🡪 樱 ). The double 貝貝, which preceded the present three hyphens, indicated "necklace"; while the single 貝 still means "shell". So you see how, by investigating the Chinese etymology, the real historical evolution is revealed. Be careful, however, because the whole right-hand side (i.e. 嬰) of the ideogram 櫻 has reason to be there solely for a phonetic reason. (Not for reasons of meaning, which is also different between Chinese and Japanese). That is, that part has been "put" there to give the pronunciation to the kanji 櫻 as a whole.

But beyond this brief digression, we still like to see it like this: like a little woman under a flowering tree. Right? Since we are dealing with the simplified character today, we can safely indulge in this reading of the kanji which, coincidentally, is very reminiscent of the image of a woman under the blossoming cherry trees. And it certainly helps a lot to remember the ideogram. After all, this flower also recalls femininity. It is no coincidence that Sakura, or the variant Sakurako (桜子or 櫻子), are quite common female names in Japan.

photo credits: pinterest.it

Ema tablets and the temples of Japan

The Japan Italy Bridge column continues to promote in-depth studies related to the world of Japan, today we talk about the Ema Tablets that we find in all the temples of Japan.

Raise your hand if you've never seen these curious wooden plates in an anime. Perhaps in a Shinto shrine, with a miko - the priestess dressed in red and white - going about her business. In any case, whether you've seen them before or not, today you can find out more.

Ema 絵馬 Japanese wooden votive tablets

Guest Author: Flavia

Translated as 'Horse Representation', Ema's are flat plaques designed to transcribe wishes and fears to be addressed to gods/spirits (kami) and buddhas. In other words, they represent a way for people to write a little message to the spiritual world. Formerly made of clay, they later began to be made of wood. Once a prayer has been written, the Ema is hung in a dedicated space at Shinto shrines as well as Buddhist temples. It is in fact a custom of Shinto origin that later spread to temples. Since they are all displayed together 'publicly', anyone can of course take a peek at them (it is important that the kami do the same).

However, it is also possible to keep them for oneself, as an heirloom. The great variety of representations, colours and styles that characterise them has always attracted the curiosity of folklorists. Together with the inscriptions on them, they represent a veritable prism through which a wide range of life stories are presented to us. A cross-section of spirituality that can show us the different colours of Japanese reality.

Ema are not the only religious objects designed to 'operate' in this sense, but they are perhaps the most widespread and can be found just about everywhere. The fact that they can be left in place distinguishes them from other religious objects such as Fuda (札) and O-Mamori (お守り). With an average width of 15 cm and a height of 9 cm, they can be very varied in size, shape and colour.

photo credits: sharing-kyoto.com/

The themes depicted can range from the following:

-

- the kami/buddha to whom the shrine or temple is dedicated (there may even be tablets depicting Thomas Edison!)

.

- the specific benefits that kami (spirits/goddesses) and buddhas are empowered to bestow;

- scenes on the origin and history of the place of worship;

- religious or cultural objects, such as zodiac animals of Chinese origin (some shrines are specifically dedicated to an animal-sign of the zodiac)

.

However, traditionally, particular importance is given to the representation of the horse, as suggested by the etymology of the name itself: e (絵) "image, drawing", but (馬) "horse".

Why the horse?

Short answer: because in ancient times people used to offer a horse to shrines and temples to obtain blessings and good luck. The figure of the 'sacred horse' still survives to this day, so much so that some religious centres use to keep one. And, if not in the flesh, in the form of a life-size model.

This sacredness of the horse originates from an ancient Shinto belief that saw the horse as an animal dear to the kami and as their messenger (although it is also important in Buddhism). One thing led to another, and so the horse quickly became a symbol carrying messages between the human world and the "other side". Or the Higan (彼岸) as it is also called in the anime/manga Noragami. (Noragami is highly recommended if you are attracted to the 'spiritual' genre, so to speak. Even through the author's fictional interpretation, it gives you a religious insight into Japan, and renders very well the relationship of the Japanese with spirituality).

Anyway, having established that our horse was considered special, the idea was to invoke a 'hand from heaven' in troublesome situations or events. For example, in times of drought they hoped for some rain (black horse) or, if not, for it to stop raining (white horse). However, in ancient times only a few people could afford to give a horse away easily. The majority of people tried to hold on to them as a valuable animal for their livelihood. Moreover, as the academic Ian Reader notes, such offerings could also prove costly for the temples if, at every prayer of some rich lord, they found themselves with a horse each time, which rightly had to be maintained, with the expense that this entailed.

photo credits: japan-photo.de

It was in response to these contingent problems that the idea of depicting the horse began to emerge. Instead of using the animal in the flesh, why not make 'e-ma' ('horse-image') instead? An affordable solution, accessible to all.

Ema thus made their first appearance at the beginning of the 8th century (Nara period), while the first evidence comes to us from the mid-10th century (Heian period). The collection of Chinese poems and prose Honchō Bunsui or Monzui ( 本朝文粋 ) would be the very first work to mention the "ema". Many others would follow, one of which was the Konjaku monogatari (今昔物語).

E-ma: the origins of the tablets

.

Ema are said to have originated as a substitute for the horse in the act of conveying one's prayers to the supreme otherworldly entities. Although some voices have been heard to the contrary of this general line. Another reading of the events would in fact have it that the plates took on the definition "ema", simply because the horse design was more popular than other themes.

This is because the theme of the design changed depending on the request. Let's say that the design of an Ema was that of a horse: the requesting party's wish could concern the welfare of their horse (think of the case of the most humble, for whom such an animal was fundamental). If the wish did not concern a horse but, for example, a physical ailment, the design would depict the painful part of the body; and so on. So "ema" according to this view would not indicate that the tablets were given the same "agency" as the animal. Rather, it simply means that there were a lot of requests concerning horses, from which an extension of the designation would be triggered.

Another interpretation, however, emphasises that the sacredness of the horse is not a purely Shinto invention and that in Buddhism, too, the animal has its own significance. Thus, the origin of the Ema would perhaps be more to be found by looking back at the role of Buddhism, on which Japanese folk traditions draw extensively. In this regard, the scholar Gorai Shigeru saw a possible origin of the Ema in a particular folk custom, related to the Buddhist tradition O-Bon (お盆). This custom consists of carving horse forms from certain plants, again for votive purposes to the souls of the dead. Gorai seems to suggest that the origin of this custom may predate that attributed to the Ema or other similar forms of representation.

Both of these dissonant rumours about the origins of the Ema do not seem to be well supported by archaeology. In fact, the archaeological findings all seem to confirm the hypothesis of the need for an alternative means of transport to the horse, which at the same time 'took its place'. Something equivalent, embodying its spirit, its symbol: its image.

photo credits: shrine-temple-navi.jp

Ema as 'living objects'

.

The proof of this would come from the language itself. There are numerous ancient inscriptions on Ema that, from a linguistic point of view, unequivocally refer to the tablets as if they were talking about the horse itself. Let us look at some of them.

In the aforementioned Honchō Bunsui there is a reference to the Ema containing the symbol 匹 ("hiki", "biki" or "piki"). Reporting from the Reader, the expression would be: "色紙絵馬三匹 "or" 3 coloured sheets of horse pictures". Nowadays used as a counter for small animals, in Old Japanese the ideogram 匹 referred to stable animals, including horses. The combination of the word "ema" with this linguistic particle, whose function is to designate a living being, speaks volumes. Similar inscriptions have also been found in two shrines in Yamagata and Saitama, dating back to the 16th and 17th centuries. In this case, we find the ideogram 疋 instead of 匹, but the meaning and reading are the same. Again from Reader, it is: "shinme ippiki" (神馬一疋) and "ema ippiki" " 絵馬一疋 ". That is, "a sacred horse" and "an image of a horse".

However, although the hypothesis on the possible Buddhist origin of the tablets was not solid, Buddhism at least in retrospect is certainly present, given the Japanese syncretism. Among other things, in the temples, the Ema serve as a means of transmitting Buddhist religious doctrine, thus assuming a further function beyond that for which they were born. We are talking about those teachings about the importance of altruism or compassion (understood in Buddhism as 'empathy') or through images taken from stories about the Buddha. Although not entirely certain, it is estimated that the adoption of tablets by Buddhist temples began roughly between the 12th and 14th centuries (Kamakura period). Indeed, many of the Emaki - scroll artworks - of the period depict the Ema or horses themselves, both in Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples.

photo credits: japan-photo.de

Wooden tablets as an art form

.

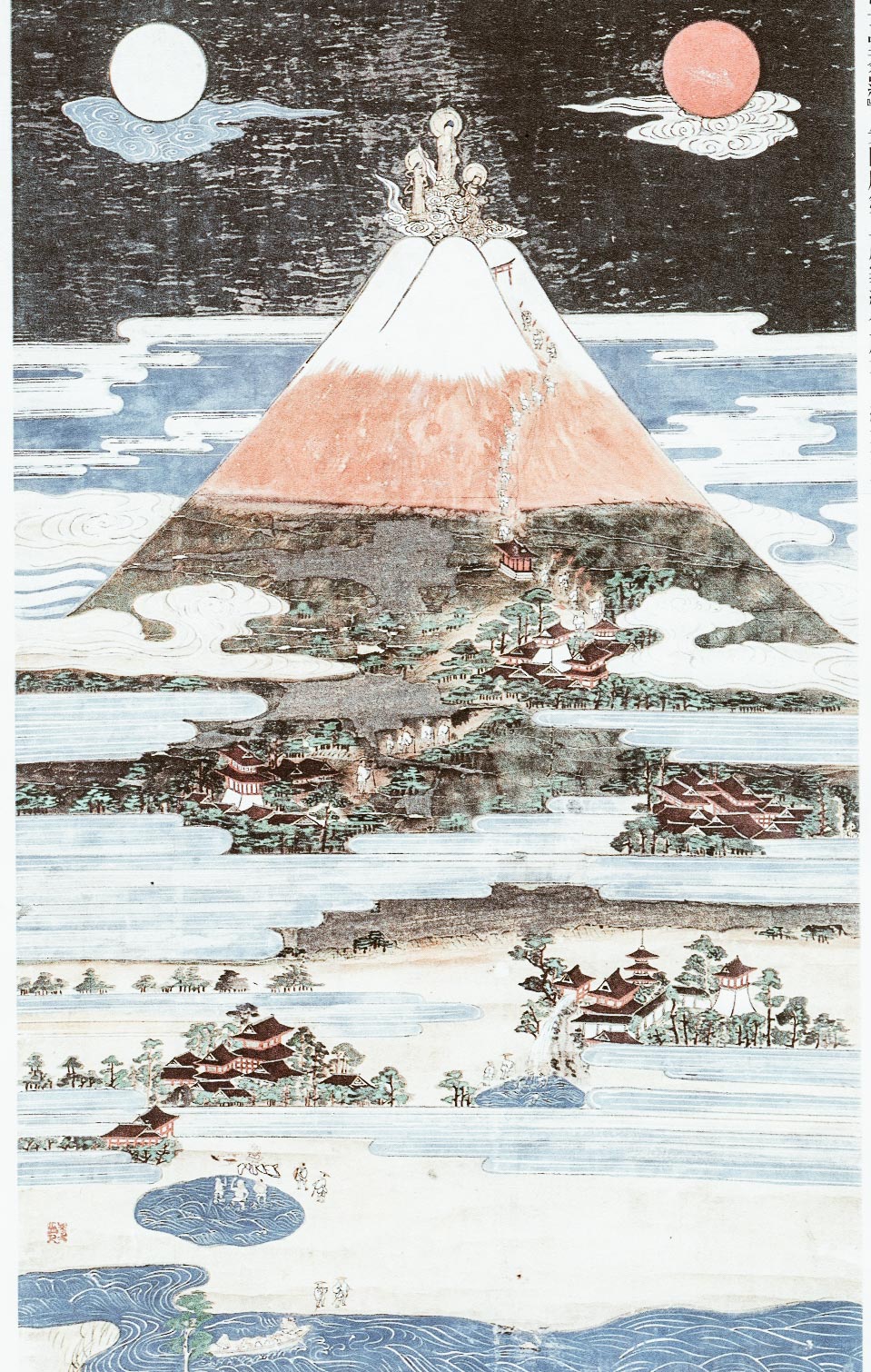

Over the centuries, the designs of the Ema became more and more elaborate and varied, giving rise to a true folk art form. In particular, the Ō-ema (大絵馬), or "big ema", proved to be an important step in the development of Japanese art. In fact, after the birth of the Ō-ema, several great Japanese artists would draw on the ema style.

Created between the 14th and 16th centuries (Muromachi period), these Ema were at least one metre in height and width. They were donated to temples and shrines as a sign of gratitude - even after the fact, not only at the time of the request - and were placed in special spaces, the Ema-dō (絵馬堂). The oldest Ema-dō seems to have been sponsored by none other than... Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1606, for the Kitano shrine in Kyoto. Also in Kyoto, the famous Kiyomizu-dera (清水寺) has several Ō-ema, originally donated by merchants as thanks for the safe return of their trading ships.

The consequence of this artistic development was the emergence of a "caste" of artists specialised in ema painting, which flourished in the Edo or Tokugawa period. This period - of economic expansion, especially at the beginning - led to an increase in the demand for professionals, enabling them to make a living from producing small ema paintings alone.

photo credits: japan-photo.de

The Ema language: symbolism

.

It was during this period that most of the symbols and themes reproduced on tablets originated. But to what does this need to put thoughts and feelings on paper - or rather, on wood - owe? This need is rooted in the folkloristic belief that a desire has a better chance of manifesting itself in reality if it is expressed in words, because by doing so, it gives it form. We must also bear in mind that in ancient times literacy was reserved for a small segment of the population. An alternative language to words, immediately comprehensible to all, was, therefore, necessary: this is the encounter between folklore and symbolism. Symbolic language thus proved to be the most effective way of doing this, through the depiction of specific problems or the desired 'grace'.

The representations could range from the well-being of children to health, fertility and even sexual desires. If, for example, a wish concerning childbirth, an Ema with a dog was the most appropriate choice. While the image of the white fox still indicates prosperity and abundance. For requests concerning health, the part of the body with the illness was also depicted. For those concerning fertility and sexuality, well: the depictions were unequivocal.

photo credits: himawari-japan.com

The type of representation can therefore be purely symbolic, drawn from tradition (see the example of the dog) or directly portray the physical object of interest (body parts). In any case, let us remember that such symbology, whether analogical or realistic, is accompanied by the thaumaturgical function of the various religious entities worshipped (spirits/gods/Buddhas). As we said at the beginning, 'protective deities' of a particular sphere of life (health, education and so on) are also a main iconic subject of the Ema. These are just examples, as subjects and styles can be as varied as people's requests and desires.

Ema language: forms and words

.

In the transition to the contemporary age, the traditional themes depicted have not changed much compared to ancient times. Of course there has been an addition of new subjects (see Thomas Edison or, why not, anime characters). However, we can observe an increase in the use of verbal language. We have already seen one reason for this: literacy. Literacy has thus added verbal language to symbolic language, allowing ordinary people to no longer depend solely on the former. So it is not uncommon nowadays to resort to linguistic games of homonymy and assonance to accompany the symbology of images.

Typical is the case of those Gokaku-ema (互角絵馬) - pentagonal tablets - with an 'educational' theme. They are designed for students, constantly seeking the support of the kami for success in their studies. Here, these Ema owe their shape to a pseudo-omonimy between the expression "gokaku" (互角) - pentagon - and "gōkaku" (合格) which indicates success in study. The subject of the Ema can therefore also be conveyed by the shape of the tablet itself! And, as you can see, it can sometimes make use of verbal meanings. A case of symbolism using verbal language is that of an Ema depicting an octopus, "tako" in Japanese (蛸) used to request help in eliminating corns. The term "callus" is spelled differently (胼胝) but is also pronounced "tako".

We can therefore see - to the delight of linguists and glottologists - that the ema language is made up of all these dimensions of communication. Symbols, shapes and words are thus integrated and intertwined in a single space. We should also remember that the graphic characters of the Japanese language derive from their ancestor pictograms, which directly represented visual objects!

photo credits: blog.livedoor.jp

Verbal language is very helpful in interpreting the meaning of a tablet's message. Because understanding the true meaning of symbolic language, needless to say, may not always be possible. Obviously, the use of verbal language does not guarantee 100% understanding, it depends on each case: there may be quite clear inscriptions, others more cryptic. The scholar Jennifer Robertson, who dealt with the Ema at the time of the Second World War, found a particular ambiguity in the tablets of this era. For this reason, she stresses the need to always take into account different possible interpretations.

Kogaeshi and Mabiki Ema, a special case

.

There is, however, a special type of Ema, where the message is neither a concern nor a need for something that is desired. A request, yes, but different from the others: a request for forgiveness. We are talking about all those plates that concern the delicate case of children, foetuses, aborted or stillborn: the so-called mizuko (水子). Ema concerning mizuko are called Kogaeshi (子がえし - lit. "sending back the baby"). Or even Mabiki (間引き - let's call it "reduction") which can refer to general infanticide.

In Buddhist temples specialising in mizuko (to which memorials are also dedicated), Kogaeshi Ema are hung in a special space, just for them, next to the statue of Jizō. In Buddhism, Jizō is a protective figure of the souls of children who died before their parents. According to belief, their spirits cannot cross the Sanzu - the river that separates earthly life from the "Other Side" - because they have not accumulated enough good deeds, due to premature death. They would therefore be condemned to pile up stones on the bank of the mystical river, but Jizō would protect them from demons and allow them to listen to mantras.

photo credits: hotoke-antiques.com

They differ from normal Ema, because their inscriptions are addressed to the spirit of the child, rather than to kami or buddha. Of course, they express all the anguish, sadness, regret of the mother or sometimes even both parents. The most common inscription, according to Reader, is a simple 'Gomen ne' (ごめんね) or 'I am sorry' ['Forgive me'] together with the reason for the gesture. This phenomenon was particularly striking at the turn of the late Edo and early Meiji periods, when extreme poverty and famine hit the Japanese population hard. The use of Mabiki Ema, however, has continued until contemporary times.

Mukasari Ema, another particular case

.

Another case of a death-related plaque is that of the Mukasari-ema (ムカサリ絵馬). In fact, these tablets were created for a singular purpose: to complete the CDs. Shirei Kekkon (死霊結婚), the marriages between dead souls. They belong to the category of large ema and, according to Robertson, their diffusion seems to be limited to Okinawa and the north-east of Japan, in the Yamagata Prefecture. "Mukasari' would in fact mean 'marriage' in the Yamagata dialect (not coincidentally written in the katakana alphabet). In essence, these Mukasari-ema allow to "simulate" in the representation of the plate, the marriage of a person who died single or unmarried. It is a way of allowing the soul to find peace, preventing it from becoming a tormented spirit.

For if that were to happen, the spirit might remain anchored in the earthly world, through grief, for not having been able to experience the joy of starting a family. Thus, haunting the world of the living. It is thus also a way for the family of the deceased person, however fictitious, to realise that dream. In modern times, one can also resort to photographs, if any, of the person in wedding attire while still alive. Such Mukasari-ema were particularly used at the time of the Second World War, for the reason easily imaginable.

photo credits: journals.openedition.org

These are two borderline cases, the exception to the rule. Because, as is now clear, the Ema are made with an eye to human wellbeing, in the here and now, be it individual or extended to the whole of humanity. But they are still part of the Ema world and, if there is something that they have in common with the others, it is a significant function: the psychological function of releasing an inner burden. The very act of 'unloading' onto the tablets what one has inside - thoughts, desires, needs and concerns - is a profoundly cathartic act. Especially if those desires and needs run counter to the norms imposed by society. As Reader notes, a way for individuals to survive in situations beyond their normal control and the only way to survive, from social control.

People's desires

.

But in general, what specifically do people who have recourse to EMA want? We could identify two macro-areas: protection and success.

Health is certainly one of them, and it is a major theme at all times. As mentioned in the introduction, kami and buddha are associated with healing powers, attributed by extension also to shrines and temples dedicated to them. Requests for 'mercy' from illnesses and diseases - or for preventive protection from any danger - may concern the applicant himself, his family members, or other persons. Requests for success, which is a very popular area, may also concern the applicant or third parties, or a 'collective self' of which the applicant is a part. This is the case of all those requests made to propitiate the success of one's own company or institution of any other nature. There are Ema's for example where the requester is concerned with the success of their favourite team (baseball is very popular in Japan).

But there is one realm that stands out above them all: education. The contemporary Japanese education system is very rigid and competitive, and the pressure of failure on children can be particularly taxing, psychologically speaking. So, you want for that reason alone. Or even for inspiration - seeing friends or groups of peers go to religious centres to write their plaques - the fact remains that students represent a good chunk of the Ema's "clientele". In addition to asking for 'heaven's favour' in the success of tests and examinations, Ema registration can represent a moment of light-heartedness for the very young.

How could we not mention at this point the kami shinto Tenjin (天神), patron of culture and education, certainly popular among Japanese students. (Incidentally, Tenjin is the deification of a person who really existed between the 9th and 10th centuries AD! A Heian court scholar and politician, in life his real name was actually Sugawara no Michizane). His shrines are busiest in the cold months, especially January and early February, when the infamous "entrance exam hell" takes place.

There is no shortage of requests concerning material well-being as well as those concerning affairs of the heart. Even those to "sever ties" with the help of the special Enkiri-ema (縁切り) to express the desire to break the cord that binds to people, things (vices, addictions) or situations (diseases).

The incineration of the tablets

Yes, this is an important stage in the life of the tablets: the final one. Both Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples periodically burn the tablets offered for a dual purpose: ritual but also practical. (In Japanese religiosity, the practical and spiritual dimensions manage to marry serenely). The pragmatic motivation is simply... the need to make space! After all, hundreds and hundreds of tablets accumulate over time.

Spiritual motivation, on the other hand, is that through the ritual of the bonfire, people's wishes and requests can reach the realm of the kami and the buddha. Kami and Buddha who, I remind you, should have already read the Ema, always available in temples/sanctuaries, before the fire rituals. Once again Noragami comes to our aid, with its story so illustrative. It is not unusual to see the Tenjin himself wandering around in the sanctuaries dedicated to him, next to the Ema tablets. Noragami also touches on the theme of severing ties, which we spoke about earlier (in short, you get the hint: watch/read it).

photo credits: https://youtu.be/Vn6AoThrXyc

When does this ritual take place?

The changeover to the new year is the moment that brings everyone together. However, it can also take place at other times, depending on each religious centre. Tenjin shrines, for example, usually do it at the end of October, just after the festivals dedicated to him.

The period around New Year's Eve, O-Shogatsu (お正月), is however ideal for everyone, being a time of transition. What better time to symbolically release what has now had its day, releasing the wishes and demands of the old year? And at the same time, what more propitious time to usher in the new year, perhaps by writing new ones? Boy, so many commissions for these kamis and buddhas from the very first sighs of the new year! The phrase "Getting rid of the old to make room for the new", in this context, can only fit well, lending itself more than perfectly to this dual interpretation.

Nothing rains from the sky!

.

But be careful not to misunderstand. Don't think that this is merely an act of superstition: nothing could be further from the truth! Resorting to the Ema is not the same as thinking of folding one's arms and waiting for an otherworldly grace. Those who resort to the EMA generally know, even with a hypothetical "favour from heaven", that 95% of the chances of success are given by their own commitment. And one's own mental attitude. I refer, of course, to all situations where one has power of action. In cases where this is not possible, the only thing to do is to try to act, as much as you can, on your mental attitude.

Ema tablets testify to the search for change or safety from some risk or danger. They have the power to approach even the most "secular", those who perhaps do not lead a great spiritual life. This may be the case for many young people, or for children, who may see in the tablets a playful side, as well as a support for their studies. The meaning of offering an Ema tablet is basically to cope with a crisis, of whatever nature, by resorting to the supernatural dimension, which has always been a source of support. In other words, the Ema performs a function of comfort and support. And, by extension, an important therapeutic function.

Okinawa and The case of the over centenarians

The Japan Italy Bridge column continues to promote in-depth studies related to the world of Japan, today we are talking about Okinawa and the case of the over one hundred-year-old population.

"At 70 you are only a child. At 80 you are a young man. At 90, if your ancestors call you to heaven, ask them to wait until you are 100 years old. Then you can think about it". So says an ancient saying in Okinawa, unfailingly quoted every time you get ready to talk about its mythical inhabitants. Words that seem to find confirmation, even in ancient legends that would speak of this place as a "Land of the immortals".

Okinawa 沖縄 The case of the over centenarians

Guest Author: Flavia

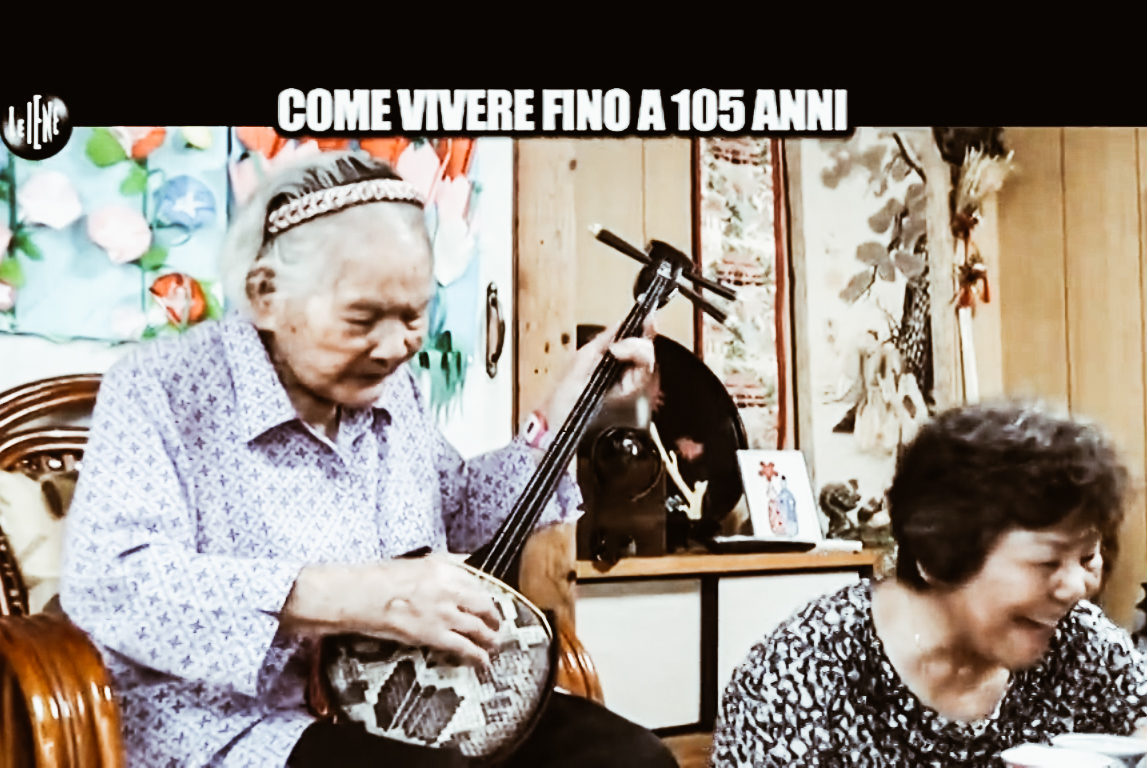

A few years ago even the show "Le Iene" brought the case of Okinawa to prime time, giving us a very nice report. The longevity of its inhabitants and even more so the incredible quality of their ageing is immediately witnessed by the first two ladies who appear in the tv show. I think that whoever saw them was amazed: I don't lie if I say that they show something like 15 years less! Unbelievable. As noted by the journalist Nadia Toffa, sent by the tv show in question, we also have them here in Italy. So the point is, how do you get to those ages. That is: with what quality of life? Usually, the pains of our elderly people, as we know, are such as to affect the quality of their last journey of life. As a society, it is now accepted that illness and loss of autonomy are what is hopelessly awaiting us when we cross those age thresholds. Well, the case of Okinawa's (super-) grandparents shows us that things don't have to be like that! And that it is in everyone's power to ensure psycho-physical well-being during, starting from ... as soon as possible! The sooner you start to treat yourself, the better you can prepare for your old age.

photo credits: mediaset.it

The typical ailments of our western societies - which often even young people(!) like to experience - Okinawa's elders almost don't know what they are. The incidence of diseases related to senility or degenerative diseases such as osteoporosis, Alzheimer's disease, sclerosis, cancer... is very low.

Okinawa: blue zone, paradise of longevity

These people have an extraordinary quality of life own on this island. We are talking about people who have never been to the hospital, who have never taken medication... who are even able to continue working or driving their car beyond the age of 90/95. Who in any case have a margin of autonomy unthinkable for a local elderly person, except in sporadic cases. Among them, the small village of Ōgimi stands out for the high concentration of centenarians compared to the total number of inhabitants. In reality, a case of similar longevity is present, you will know, also in our house: in the nearby Sardinia. Not by chance: Okinawa, Sardinia, the Greek island Ikaria, the Costa Rican Nicoya and a small community near Loma Linda in California, all fall under the name of "blue zone".

photo credits: ilviaggio.biz

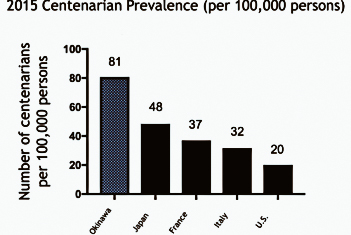

Any area in the world where life expectancy is higher than the general average is called the "Blue Zone". Real "paradises of longevity" that attract researchers from all over the world to try to capture the "secret" of their populations. In this sense, Okinawa and its inhabitants even surpass even mainland Japan, which does not lag behind in terms of quality of life, but has a higher incidence of disease, for example.

photo credits: orcls.org

photo credits: orcls.org

But who are the Okinawans? Let's first find out who we're dealing with.

Identikit of the Japanese "tropics"

Okinawa is the main complex ( 沖縄諸島 Okinawa-Shotō ) of the Ryūkyū archipelago and is located between "mainland" Japan and Taiwan. It consists of a main island of the same name plus other smaller islands. Naha ( 那覇 ), is its capital. It was named prefecture of Japan in 1879 although the Ryūkyū complex ( 琉球諸島 Ryūkyū -Shotō ), which incorporated it, was formally annexed in 1874. At that time Japan was in the process of modernization and this was matched by a process of unification of all the territories of the archipelago under a single flag.

photo credits: lacooltura.com, pinterest.it.

Before 1874 Ryūkyū was an autonomous kingdom, whose foundation in the 15th century led to the unification of the islands of Okinawa. Formally it was recognized by the Tokugawa - lords of Japan until 1868 - under the jurisdiction of the fief of Satsuma (today Kagoshima Prefecture). In fact, however, it was independent, so much so that it was the fiscal kingdom of both Japan Tokugawa and, even before that, China.

Okinawa is a rather peculiar region, more in its own right than the rest of Japan. It is influenced by China and South-East Asia, due to the frequent trade and cultural exchanges maintained by the Ryūkyan Kingdom over the centuries. Okinawa cuisine itself and Karate, the made-in-Okinawa martial art par excellence, are the result of such interactions.

The lush nature of these islands, made up of numerous coral reefs and extensive rainforests, together with a sub-tropical climate, makes Okinawa a true paradise. It is not uncommon to find it referred to under expressions such as "tropical corner" or "Caribbean" of Japan. A climate that is somewhat reminiscent of that of the blue zones of Sardinia and Ikaria, which are also islands. I am not surprised that paradises like these can host "elixirs" of long life.

But let's see what researchers' discoveries tell us about Okinawa's elixir.

The ORCLS researchers' studies

The Okinawa Centenarian Study (OCS), is the longest centenarian study currently in existence. It is conducted by the Okinawa Research Center for Longevity Science (ORCLS) research team, which has been reviewing various aspects of local life since 1975. Among these, social, psychological and spiritual aspects are also given high consideration. Professor Craig Willcox, interviewed in the service by the Hyenas, is one of the leading researchers. Willcox tells the Hyenas' cameras about the discoveries his team has made over the years. First of all, the presence of a particular gene, FOXO3, readily christened the "longevity gene", was observed. However, the researchers found that longevity and longevity quality are inversely proportional to a number of health risk factors that were present before the age of 50. That is, the chances of reaching at least 85 years of age in good health increase if there are no more than 7 risk factors before middle age. Conversely, with more than 7 factors, Willcox tells us that the odds can be as high as 0%.

And here are the risk factors:

- Hyperglycemia (with risk of diabetes)

- Hypertension (with risk of heart attack or stroke)

- Excessive alcohol consumption

- Low level of education (education would foster a greater awareness of what it means to have a healthy lifestyle)

- Being overweight

- Poor diet (lack of vitamins, proteins, mineral salts)

- High triglycerides (with risk, for example, of arteriosclerosis)

- Low gripping force in the hands

- Smoking

- Only for men: don't be married!

The latter is quite curious, as Toffa immediately notes in his interview. Willcox motivates him as follows: "women are much better [at taking care of themselves] they don't need men, they can survive without them". This is why having a woman at your side would increase the life expectancy of the average man. However things may be, if we think that historically Okinawa women play a key role in Okinawa society, this could take on a wider meaning. And good Okinawan women!

Not only Okinawa DNA

But the research does not end there. Willcox says he and his team examined a sample of 8000 men with Japanese ancestors in their genealogy. Considering the two analysis variables, presence of the FOXO3 gene (1) and healthy lifestyle (2), they divided the subjects into 4 groups. Well: the individuals who possess the gene linked to longevity, however, have an incorrect diet, live less than those who, although not genetically predisposed, maintain a healthy diet. This clearly shows us - as Willcox says - the power that a healthy diet and lifestyle have on the physical health of individuals.

photo credits: mediaset.it

Another thing observed is that the Okinawan population does not consume more than 1100 calories per day. This is 10% less than the calories usually indicated by each nutritional table. In particular, their habit of "nibbling rather than bingeing," Willcox always explains, "is key. But a snack made from healthy food: snacks, for example, are made from dried fruit or dried fish (a snack that is also common in mainland Japan). All this in conjunction with a broader, healthier lifestyle.

Shall we find out in detail what all this consists of? Let's start with eating habits.

#1 Traditional diet

Two, are basically the principles underlying the Okinawan diet and concern quantity and quality of food.

腹八分 (Hara-Hachi-Bu): " stomach [full] for 8 parts"

That's 8 parts out of 10: "Always leave some space in your stomach...that is, eat until you are 70-80% full" explains Willcox. A guideline, it would seem, of Confucian origin, which seeks moderation rather than satiety: never fill up completely but eat what is strictly necessary. And in fact, the second elder tells journalist Toffa: "I eat what is right but never fill myself completely. I always get up with a bit of hunger".

The Okinawans are used to eat 5 meals a day (which is also recommended by local doctors), opting for low-calorie but satiating foods. Let's keep in mind the setting of the table, which is typical of Japanese cuisine. The contemporaneity of the dishes, through their arrangement in saucers and bowls, is a factor that certainly predisposes more to "small tastings" than to binge.

photo credits: travelbook.co.jp

I-Shoku-Dō-Gen ( 医食同源 ), "food and medicine, same origin", from Okinawa

For the local elderly, there is nothing healthier than lovingly caring for the garden and then feeding on the fruits of the earth. If we add marine food to these, we have our own miracle diet. This is what it is made up of:

- Greens. Especially with green leaves, yellow roots and orange roots, all containing carotenoids and anti-inflammatory agents.

- Tubers like the sweet purple potato of Chinese origin, with a very low glycemic index. Eugenio Iorio, an Italian researcher, explains: "it is there [in the purple] that these famous polyphenols [...] dialogue with our DNA and therefore help us to control the effect of free radicals";

- Legumes. Like soya beans (with protein and fibre but without fat) and soya derivatives;

- Algae, natural anti-inflammatory, ideal for free radicals and also for hair;

- Fish and the already mentioned dried fish, rich in magnesium and omega 3;

- Tea. Especially green tea and jasmine tea, anti-ageing;

- Herbs to chew like Sakuna, "herb-elixir" slimming and antioxidant;

- Fruits. Among which bitter melon Goya, used in the typical dish "Goya Champuru" and citrus Shikuwasa, anti-inflammatory, both typical of the place.

photo credits: ohayo.it

"Eating like a rainbow"

In the words of Dr Willcox, by virtue of the parade of colours that the great variety of fruit and vegetables brings to the tables of Okinawa. Variety. Another watchword in the agenda of the Okinawans who would use at least 18 foods daily. The important thing, however, is always to respect the seasonality of the fruit and vegetables. In this way, the maximum nutritional potential of the fruit and vegetables can be realised. And of course, the freshness of the food. It is also important if you decide to cook them, especially when it comes to fish and vegetables: never overcook them if you want to preserve the nutrients!

In addition to very low consumption of carbohydrates, salt and sugar are also used very little. Yes to spices, such as turmeric, and mushrooms.

What about meat?

As a result of that Chinese influence mentioned at the beginning, meat consumption is also well established in Okinawa's cuisine. But meat, as well as dairy products and cereals, are categories with a high nutritional density...so they are consumed in even smaller quantities! Even rice is eaten less than the rest of Japan and quinoa is often preferred to rice. We speak of a low-calorie diet also for this reason; because it counterbalances with smaller quantities of nutritional contributions otherwise potentially excessive. Also because vegetable and marine foods and fruit remain the true carriers of all those beneficial substances that make up the food elixir of Okinawa.

#2 Motor and mental activity

"When the body moves, the brain goes into rhythm" - this is the motto of Jim Kwik, an internationally renowned trainer who deals with fast learning. Kwik always urges even those who have to spend their days sitting down for work or study not to stay in the chair all the time but to take breaks and move around. Even just a few minutes of simple movements between breaks, as well as drinking water and making small snacks, are enough. In doing so, Kwik suggests, our performance is even better, because the brain works better if we treat ourselves this way. Exercise as a stimulator of neurogenesis and neuroplasticity: facilitates the creation of new neural connections. In short, physical movement is also a gym for the brain! That comes out strengthened. And if the brain is active the whole organism benefits. It is a vicious, beneficial circle that, when activated, becomes self-feeding. And this is also the basis for all the nutritional discourse that has just been made, as well as the other factors that we will see in a moment. Let us bear in mind that this discourse is not compartmentalised: everything is connected.

photo credits: okinawa.stripes.com

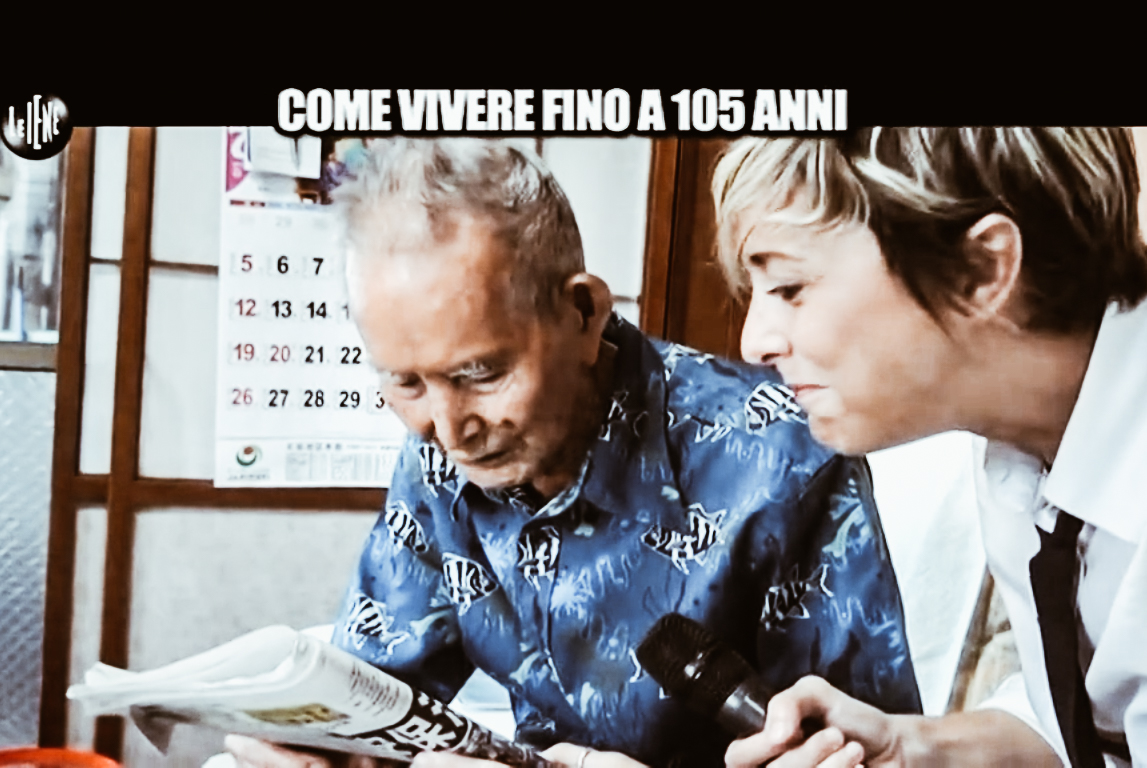

Observing the lives of our Okinawans, we find that, in their own way, they put into practice very similar things to those promoted by Mr. Kwik. The second reason for their well-being lies in the fact that they are active, not only in their body but also in their mind! The grandfather we see in the hyena service, for example, reads the newspaper every day when he returns from his morning walk. And watch out, 100 years go by, he does so without the help of glasses. Not to mention the fact that he worked in the countryside until he was 97 years old!

photo credits: mediaset.it

Among the activities most loved by Okinawa's grandparents - in addition to the garden, as already mentioned - we find traditional dance or dabbling with some traditional musical instrument. Or, martial arts, ideal for the body-mind-spirit system, as in the case of master Seikichi Uehara. Uehara, a few years before his death at the age of 100, still taught Karate to his students. Or again: how not to mention the weaver Toshiko Taira who, at the age of 100, continues to work as a weaver of Bashōfu, an ancient fabric used for the Kimono (produced only at Ōgimi).

#3 Interior and exterior attitude

But it's not just a question of genes and nutrition. Turn that turns you back, you always come back there: the mind (and the spirit, which in the Japanese vision is one with the mind - as the parola心 "Kokoro" or heart/mind) testifies. Once again, the vision of things proves to be decisive. The most cynical ones will be tired of always hearing "the same old tune", I know; but instead of automatically throwing it on scepticism, I would start to give more credit to the "power of the mind". There will be a reason for this if it is invoked from many quarters. Those who have somehow experienced the beneficial influences of a clean mindset, from excessively... interpretative distortions of reality, let's put it this way.

The perception of the world and therefore of oneself has the power to affect the tangible world of people. Let's think about psychosomatic illnesses for example...or even just inner dialogue: thoughts or words directed towards something can influence this something, including ourselves.

Thus, even Okinawan scholars recognise optimism as a not inconsiderable factor, as well as more tangible factors. Optimism, attention, understood not as pretending that the challenges in life do not exist...but as a different way of accepting both the good and the bad. An openness towards life, which avoids complaining and the negative vision of things. A serenity given by knowing one's own soul and place in the world, with a consequent trust in life and in others. From giving the benefit of the possibility, to everything and everyone.

photo credits: mediaset.it

#4 Interpersonal relationships and social life

When this happens, the mind/spirit "machine" works properly and you feel better at 360 degrees. Even in the seemingly obvious little things that have their own importance, such as simple but authentic moments of conviviality. People in Okinawa generally have a very healthy social life, based on trust and balanced communication. It is often overlooked, precisely because it may seem like "the usual rhetoric", but, believe me, communication is essential to maintain healthy and satisfying human relationships. When people manage to have sincere, spontaneous, and serene communication - without any quarrels of any kind - the relationships are perfectly balanced. Without balanced and satisfying human relationships, the life of a human being is not the same. Just as moments of healthy solitude are essential, to rebalance oneself and recover one's energies, so, at a certain point, are human relationships. But be careful: they must be healthy and balanced. Just like those of our Okinawans.

The deep sense of belonging to the community that characterises their network of relationships and the value attributed to the elderly creates a buffer effect on the elderly that gives them confidence. With a community ready to support them, grandparents can thus live freely and still feel useful. Would you have me believe that the love and trust surrounding these people do not contribute to their quality of life?

#5 Spirituality

And all this takes us towards the last factor that remains for us to consider: spirituality. It "ferries us" because an approach to life like the one we have seen, from that part of the world, goes hand in hand with a certain kind of spiritual sensitivity. These two things are intimately linked if we think about it, and it could not be otherwise.

The philosophy of finding one's own reason to live, what gives it meaning, is from Okinawa, the famous Ikigai ( 生き甲斐 ). If this is missing, there is no healthy diet or strong genes to keep, for a long and quality life. Even the saying "Nan kuru nai sa ( なんくるないさ )" that is "Don't worry [it's all right] " is made in Okinawa. It indicates the profound belief that everything that happens in life has its own intrinsic meaning and that it serves us, for our growth. Having said that, everyone can and should do everything in his or her power in the situations that life confronts him or her with. If this is done, then the motto says to us "you have nothing to fear: everything you could do you have done, so it is all right, be at peace. Everything is as it should be".

Prayer and meditation, also beneficial against stress, are very present in the life of the Okinawans. In the morning, for example, they gather in front of an altar traditionally present in their homes to commemorate and thank their ancestors. This aspect of thanksgiving is something very important that potentially has an impact on the mentality and one's own worldview. And the same care of the vegetable garden already invoked higher up or even eating calmly (devoting all the attention to the act itself, without dispersing it with the TV, for example), is in truth in itself, already meditation.

Nature and environment

A spirituality in any case always close to nature...that recognizes the soul. Could it be that it is precisely the sharing with nature that has inspired these people over time to the right behaviour for a beneficial lifestyle? Although this specific aspect is difficult to quantify with empirical data, I believe so. Also because, if we take for granted that mentality and worldview can have power over our lives... why then discard a priori the power of the "spirit of nature"? Just like animals (think of pet-therapy), so can nature.

The spiritual is very present all over Japan but in Okinawa, it can count on a more uncontaminated nature, at least, compared to other places in the world. Let's remember that the increase in free radicals - potentially responsible for cancer - is also favoured by pollution as well as by bad behaviour. In order to link up with what we said at the beginning when we were thinking about the other blue areas, even the environmental factor - the ecosystem - has its own weight.

photo credits: visitokinawa.jp

The power of the Okinawa lifestyle

And so, alongside: healthy and balanced nutrition; the balanced activity of body and brain; a good relationship with life and consequently with others, here we have the spiritual dimension. But again, there is no hierarchy between these factors: just like the courses of the Japanese tables, they are all contemporary. Each one depends on the other and each influences the other. Of course, you will say, there is always a genetic predisposition. But while genes are not chosen, all these factors are in the hands of individuals. They are in their power. Good genes are undoubtedly a plus. However, as widely observed in OCS research, an individual with a healthy lifestyle lives better and for a long time, even without such a gene. While its effectiveness can also be cancelled out by the lack of just one of the other factors. This is already being demonstrated by the new generations of Okinawa. In fact, the young people of the area are at risk of losing the health benefits of their grandparents by becoming westernized between sedentariness and technology, consumption of pre-packaged food full of colourings.

Even in Italy, it is possible to have the same nutritional benefits as the Okinawa diet. After all, our Mediterranean diet, as Eugenio Iorio also tells us, is based on the same principles. Therefore, we also have the same food supplies in our lands and in our sea. We also talk about "MediterrAsian diet" if we try to integrate the two nutritional models. On the other hand, the Okinawa lifestyle and the Sardinian and Ikarian styles have some aspects in common: high consumption of vegetables and legumes, active and especially outdoor life, and finally, social life and strong family ties.

Fuji san, a deep focus on the symbol of Japan

Snow-capped peaks, dizzying slopes, harmonious and perfect shape: Mount Fuji. Breathtakingly majestic, a famous cultural icon: a mystical and spiritual place. There are no words to describe what it feels like to be in front of this wonder of nature. Its importance is such that it is often said that, more than a symbol of Japan, it is Japan.

Mount Fuji 富士山 The symbol of Japan

Guest Author: Flavia

Fuji (富士山 Fu-Ji-San) is located in the Chūbu region (中部地方), about 100 km southwest of the capital Tokyo. It lies between the current prefectures of Yamanashi and Shizuoka, with Kanagawa prefecture to the east. The entire area is part of the Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park (富士-箱根-伊豆-国立公園Fuji-Hakone-Izu Kokuritsu-Koen). Together with Mount Tate (立山) and Mount Haku (白山) is part of the CDs. Three Sacred Mountains ( 三霊山 San-Rei-Zan ) so identified because they are sacred to the Japanese tradition.

The numerous cultural-historical sites around the mountain testify to the great spiritual significance that has always been attributed to it. In pre-modern times it was, in fact, a pilgrimage destination for monks engaged in spiritual research and self-discipline, as well as for ordinary people.

Today this religious connotation has been lost. Although the idea is still widespread that climbing to the top of Fuji at least once in a lifetime is almost a religious duty. Nowadays, climbing is also facilitated by modern means, thanks to which the route to be made on foot is more than halved!

Source of inspiration for a vast cultural production (literature, poetry, art...), its influence has reached the West. It is now well known how much the prints of the masters Hokusai and Hiroshige, portraying Fuji, influenced Monet and Van Gogh.

The fact that it appears among the yen bills and in the name of the main television station is indicative of the central role it plays for the people of the Rising Sun. So much so that it is classified as a "Special Site of Scenic Beauty" and protected as cultural property by the Agency for Cultural Affairs (branch of MEXT). In 2013 it is declared World Cultural Heritage by UNESCO. It is included in the category culture - rather than nature - because its impact goes far beyond its natural essence. There are at least twenty-five sites of interest recognized by UNESCO, on Japan's most important mountain.

photo credits: expedia.it

Fuji Geological History

Fuji is classified as a stratovolcano, a volcano formed by the accumulation of layers of solidified lava and volcanic ash. Its particularly steep slopes, its perfect conical and symmetrical shape are the results of this overlapping process. It has a crater with a diameter of about 600 meters, 250 meters deep, and at least 70 small secondary peaks including Mount Hōei and Omuro. Its volcanic activity began more than 100,000 years ago.

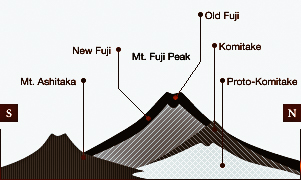

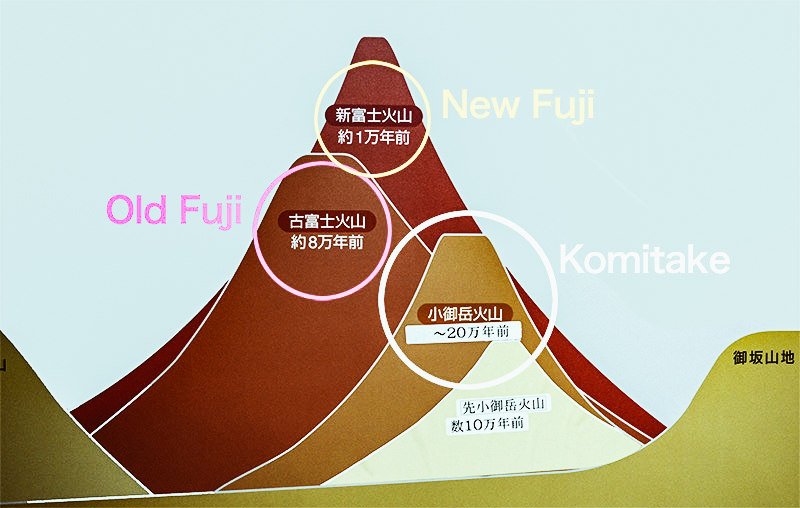

It was long agreed that there were three stages of the stratification process, called "Small Peak" (小御岳Ko-Mitake), Old Fuji (古富士Ko-Fuji ) and New Fuji (新富士Shin-Fuji). Since 2004 new studies and explorations have revealed the existence of a fourth phase Proto-Komitake (小御岳 Sen-Komitake). It is currently believed that the Komitake originated as a result of eruptions produced by the Proto-Komitake hundreds of thousands of years ago. Just as about 100,000 years ago an eruption of the Komitake gave rise to Old Fuji, the summit of which reached about 2,700 meters with subsequent eruptions. So the Fuji over the millennia has been gradually shaping itself. It reached its present form about 10,000 years ago, after Old Fuji and Komitake also disappeared under the layers of lava.

It erupted nine times between 781 and 1083, and then it remained quiet for a few centuries. Its last eruption - which formed Mount Hōei - dates back to 1707, which for a while led to classify it as dormant. But around 1960 there is a change of definition: it is defined as "active" every volcano whose eruption has ever been documented. In 2003 a further update extends the definition to every volcano that has ever erupted in the last 10,000 years and that continues to give signs of activity. Under these last two designations, Fuji is now considered active. It ranks at 5 in the Volcanic Explosivity Index on a scale from 0 to 8 (like our Vesuvius and Etna).

photo credits: web.archive.org

Geography and territory of Fuji San

Thanks to its 3,776 meters of height, our Fuji is undisputed as the highest peak in Japan. However, between 1895 and 1945 it was climbed by another mountain! How? Because of the post-war agreements closing the first Sino-Japanese conflict, with the Treaty of Shimonoseki, when Taiwan came under Japanese control. Therefore, formally, in those years Taiwanese territory was Japanese. Thus, the Taiwanese "Jade Mountain" (玉山 Yu-Shan) - then called by the Japanese "New High Mountain" (新高山Nii-Taka-Yama) - with its 3,952 meters manages for 50 years to overtake Fuji-San.

There are three towns on its slopes (whose names also characterize three of the main access routes to Fuji): Gotemba (御殿場) to the east, Fujinomiya (富士宮) to the south-west, Fujiyoshida (富士吉田) to the north.

Five, the lakes (富士五湖 Fu-Ji-Go-Ko) that surround it: Yamanaka (山中湖); Kawaguchi (河口湖); Saiko (西湖); Shōji ( 精進湖 ); Motosu (本栖湖). Curiosity: the latter in particular would be the Japanese version of Loch Ness. Legend has it that in 1970 they sighted a creature of 30 meters with rough skin and full of humps: it was promptly christened Mossie!

Near the lakes, to the north-west, we also find a forest of 3000 hectares: Aokigahara (青木ヶ原), also known as Jukai (樹海) or "sea of trees" (sadly known for the primacy of suicides, second only to the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco). The area is also rich in caves and hot springs.

Mishotai (御正体山) and Shakushiyama (杓子山) in the northeast, Kurodake (黒岳) in the north and Kenashi (毛無山) in the west, are the closest peaks from which you can see Fuji in the front row.

photo credits: itinari.com

Fuji, etymology and meanings: But what does "Fuji" mean?

The first thing to note: the name "Fuji" already existed before the introduction of Chinese ideograms or sinograms. The characters used to indicate it were therefore chosen according to their pronunciation so that the latter would coincide with the pre-existing pronunciation. Written as it is today, i.e. 富士山 (Fuji-San), it is given the meaning of "Prosperous Mountain".

There are, however, different opinions that in the past "Fuji" meant something else. Everything always depends on the writing: the same pronunciation can correspond to more than one meaning. Ergo more words, distinguishable at that point from the writing (as well as the context).

Here are the most popular theories about the meaning of Fuji:

- Unparalleled Mountain【不二山】: very popular is the theory that the name of the volcano was originally written with these Kanji-ideograms- to mean "Unrivaled Mountain" (二 is the number two, so "not two").

- Monte dell'immortalità【不死山】: This interpretation is based on three works of the past: the ancient Chinese chronicles "Shiki" (史記), the Taketori Monogatari (竹取物語) and the Fuji Sanki (富士山記). The first reports the existence of an elixir of immortality on top of the volcano; the third describes the mountain as the home of immortal beings. The fire of Fuji so metaphor of the inexhaustible "fire" of life. The Taketori Monogatari suggests another etymology, however, that of "mountain rich in warriors" (富 = abundance, 士 = warrior).

- Winterless Mountain【不尽山】: Many people bring back such "inexhaustible being" to the snow because the summit is almost perpetually covered with snow.

These are still theories but, I must say, this last interpretation would be quite precise. Personally I do not disdain even the alternative of the "Mountain without equal", it is certainly right!

The misunderstanding "Fujiyama"

Speaking of Fuji names, it seems necessary to open a parenthesis on the issue "Fujiyama". If only for those who do not know the language. Since it has escaped the pen of its first transcriber, you might also come across this term in some tourist guides. Well, this is a linguistic misunderstanding! An error dating back to the first transcriptions from Japanese to Western languages.

The character 山, which indicates the mountain, is pronounceable with the Chinese reading "san" but also with the Japanese reading "yama". The Chinese reading (on'yomi) is clearly due to the fact that the ideograms come from China. The reading of Chinese origin is mostly taken when you have compound words, otherwise, the Japanese one (kun'yomi) is used. The exceptions are not rare, but Fuji is not among them.

That's why using "Fujiyama" as a translation of "Mount Fuji" (富士山) is an error. 山 " 山 " alone can be read "yama", but next to the name "Fuji" takes the pronunciation "san". Therefore, "Fuji-San" is the only correct pronunciation for 富士山 [Mount Fuji].

If ever, the form "Fuji no Yama" (富士の山 "Fuji mountain") would be admissible since 山 and 富士 are divided by the specification particle の. Actually there is also this expression, but it is obsolete, found in ancient literary works. Some also recognize the possible contraction of this rare term from "Fuji no Yama" to "Fuji-Yama". Even if it was, the eventual absence of the particle の assumes the presence, however, as much as it is understood. This is not the case in the wrong transcription "Fujiyama", where nothing is contemplated between "Fuji" and "Yama". Then, the latter is always an error.

Other courtly or disused versions are:

- Fu-Gaku (富岳 "Abundant Top");

- Fuji no Takane (富士の高嶺 "High peak of Fuji");

- Fuyō-Hō (芙蓉峰 "Lotus Summit").

photo credits: kyuhoshi.com

The sacredness of the mountains in the Japanese tradition

Mountains and volcanoes have always had a special place in Japanese spirituality, which has given them a special meaning since the beginning. They are seen as mysterious places, home to spirits as good as bad. A mountain or a volcano is definitely a special, sacred place. A deity, or the seat of one or more gods, perceived by the people as the protector of the whole community.

This autochthonous sensibility - pre-existing to Buddhism - was a form of shamanism that resulted in those beliefs and practices that constitute Shintoism. Shintō made nature an object of worship as an earthly manifestation of the Kami (神 Divinity). Not only the mountains but also the rocks, trees, rivers and waterfalls, lakes...all are perceived as the earthly expression of the Kami. Fuji for example is also defined in Shintō as "Yama no Kami" (山の神).

This Shintō practice of mountain veneration is part of the Kannabi Shinkō (神奈備信仰 "Kannabi Faith"). Kannabi" are all those sacred places used to celebrate and give thanks to the Kami; in the case of mountains, the gods or spirits of the mountain.

This autochthonous conception is then intertwined with the Buddhist vision of the mountain as an ascetic place for the search for enlightenment and the realization of Buddhism; the Taoist one, of the mountain as a mystical place, of Yin-Yang harmony and the five elements; the Confucian one, of the mountain as a cosmic place that connects all living beings in the common search for harmony and self-realization (not in a selfish sense, of course).

photo credits: tripadvisor.com

The ancient faith Fuji: why worship a mountain?

The question is very simple but full of meaning. The Japanese have always looked at Fuji - at nature in general - with the eyes of a child, I dare say. With attention to its behaviour, reacting and adapting their actions accordingly. To begin with, and before anything else, this "looking", alone, is distinctive of the type of approach that distinguishes these people. Then comes into play as they have observed, that is, with attention. Which brings us to step three: their response after what they have caught. An answer as pertinent as the initial, careful, observation. An answer that communicates nothing else but the acknowledgement "I have recognized you, I have recognized your existence; I respect your will". Only a careful perception could lead to this kind of response.

So think of Fuji, so imposing, so perfect...and so explosive in ancient times: the ancient Japanese could only be impressed by such a manifestation. The first settlements of which there are traces are very ancient: they date back to a period between 11,000 and 13,000 years ago, called Jōmon Incipiente (very first Japanese prehistoric era). Well, among other things, stones have been found, whose arrangement indicated unequivocal ceremonial signs!

Its power, together with its grandeur, led the ancient Japanese to fear it and admire it at the same time. They came to the conclusion that that volcano so powerful had to be the expression of a deity or just a deity (神Kami). For obvious reasons, they tended to consider it a deity of fire. So the Fuji began to be worshipped with the intent to avert its eruptions, inevitably interpreted as the wrath of the deity present there.

The nature of this ancient autochthonous faith remains, in any case, a little mysterious, but it should not be surprising. After all, we are talking about really ancient times.

Fire and Water: the dualism of Fuji-Kami

.

One thing, however, that can be seen with more confidence is that double attitude/reaction of admiration and fear on the part of the ancient Japanese. Despite its smoky character - pass me the term - of the time, Fuji was not perceived as a mere intractable or evil divinity. It was simply what it was. And the Japanese ancestors also considered its positive aspects...almost all of them converging in a single word: water.