Samurai flags at the Tokyo Olympics

Samurai are still very respectable and important figures, so as the Tokyo Olympics approach, a content producer is hoping to spark greater understanding between nations with anime characters wearing traditional Japanese clothing.

Flags of countries revised as samurai for Olympics

Author: SaiKaiAngel | Source: The Japan Times

Kama Yamamoto along with other artists launched World Flags in 2018 with the idea of helping people around the world become familiar with their cultures in a fun way and says, "I want the project to be recognised globally as something that can unite the world through anime and samurai."

Yamamoto's idea is to use characters in samurai or traditional Japanese clothing to illustrate different nations, their flags and increase interest in Japan.

Here are some examples:

the Peruvian character Vargas is depicted as a ninja in red and white carrying a leaf-shaped kunai and, in the case of Chile, the condor, which is the national bird, is perched on the shoulder of a samurai, while the Canadian character wears a red and white kimono with a maple leaf on its sleeve.

Yamada says a lot of work is underway to get the initiative officially recognised by the Tokyo Games organisers.

Yamamoto's background is in educational personification books; he has drawn manga characters to represent jobs ranging from tapioca shop owners to web designers. The books are aimed at children and include information on average salaries and what it entails to better inform children about the choices available to them when they grow up.

photo credits: The Japan Times

The educational purpose remains with World Flags.

There were about 80 characters on the website at the beginning of December, according to marketing producer at Digital Entertainment Asset Hiroshi Tsuruoka. The site is regularly updated with new personified flags.

Characters are introduced on the project's official Twitter page as soon as they are ready. With over 15,000 followers, the page also boasts fan art posted by those inspired by the characters.

However, characters can undergo both physical and "personality" changes in line with advice or criticism from people around the world, helping them to become more suited to the country concerned.

In one case, the Spanish flag, whose character is called Iniesta, was initially portrayed as a bullfighter, but was later transformed into a flamenco dancer following criticism that bullfighting was a controversial topic in the country.

The project got what Yamada called its first "big break" in the summer of 2019, when the Chinese flag depicting Aaron was widely shared online. Yamamoto soon began receiving interview offers from Chinese media, along with offers to create a range of merchandise e.g. mouse pads that are currently available online.

The characters are illustrated by a group of artists brought on board by Yamamoto, many from his previous projects.

"Some of the illustrations are by full-time artists, but others are drawn by people ranging from housewives to vets who draw as a hobby," he says. The flags are assigned by Yamamoto, who brainstorms a rough idea of the character design, to individual artists based on their illustration styles.

photo credits: The Japan Times

While Yamamoto works to finish personifying all the countries, a number of people from smaller nations have expressed delight at finding their respective flags in samurai form.

Some, including Mexico and Venezuela, have even received framed images of their personified flags at their respective embassies in Tokyo.

"We believe that an anime-style character representing Mexico can be an ideal way to convey the long-standing friendship that exists between the Mexican and Japanese people," Emmanuel Trinidad, the cultural affairs adviser at the Mexican embassy in Tokyo, said in an email.

"Every comment received about it on social media seems to praise the fact that the work goes beyond any stereotypical image and instead presents a fresh and more modern approach to the characters representing the countries in general."

The project was first published as a book last year, with illustrations of the characters and information ranging from national demographics to the number of Olympic medals won by the nation in question.

They would also like to turn it into an anime or superhero movie in the future, with the characters joining forces to fight an enemy to save the world.

"The story will not have a protagonist, and all the characters will work together for a common goal," says Yamada.

Yamamoto initially hoped to complete the project in 2020 ahead of the Olympic Games before they were postponed due to the new coronavirus pandemic. Now he is aiming to present around 200 personified flags by the end of this year. will he be able to achieve his goal of uniting countries with Japan? we are sure he will. Let's look forward to it and enjoy these works in the meantime!

Japan History: Asakura Yoshikage

Asakura Yoshikage (12 October 1533 - 16 September 1573) was a Japanese daimyō of the Sengoku period (1467-1603) who ruled a part of Echizen province.

Asakura Yoshikage, head of the Asakura clan

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Asakura Yoshikage was born in the Ichijōdani castle of the Asakura clan in Echizen province. His father was Asakura Takakage and his mother seems to have been the daughter of Takeda Motomitsu.

Yoshikage succeeded his father as head of the Asakura clan and lord of Ichijōdani Castle in 1548, demonstrating great skill in political and diplomatic management, especially through his negotiations with the Ikkō-ikki at Echizen. Thanks to them, Echizen enjoyed a period of relative peace compared to the rest of Sengoku-period Japan, becoming a place for refugees fleeing violence in the Kansai region. Ichijōdani even became a centre of culture modelled on the capital of Kyōto.

Ichijōdani Asakura Family Rovine storiche | photo credits: wikipedia.org

Conflicts with Oda Nobunaga

After his capture in 1568, Ashikaga Yoshiaki appointed Yoshikage as regent and enlisted the help of the Asakuras to drive Nobunaga from the capital. In 1570, Oda Nobunaga then invaded Echizen and succeeded in invading the castle due to Yoshikage's lack of military skill. Azai Nagamasa, Yoshikage's brother-in-law, attacked Nobunaga with the Asakuras at Kanegasaki, but Nobunaga withdrew his troops and managed not to be captured. At the Battle of Anegawa, Yoshikage and Nagamasa were defeated by the superior forces of the Oda and Tokugawa clans led by Nobunaga and Ieyasu.

Death

Yoshikage fled to Hiezan after the battle and attempted to reconcile with Nobunaga, which enabled him to avoid conflict for three years. In 1573, during the siege of Ichijodani Castle, Yoshikage was betrayed by his cousin, Asakura Kageaki, and was forced to commit seppuku at the age of 39. His death also destroyed the Asakura clan.

5 must-see destinations for 2021

We all need to feel free again, why not do it as soon as everything ends with special destination Japan? We are called Japan Italy Bridge, obviously we love Japan, but we recommend it to everyone. Those who have been there will want to return, those who haven’t are dreaming of going there.

The 5 destinations in Japan not to be missed according to Japan Italy Bridge

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: expat.com

Japan should be seen and experienced, because each of its smallest part can give us something unique, can enrich us with experience and tradition, if you rely on the experts of JNTO you can go on the safe side! Japan is not only an unmissable destination, but it’s also completely safe, with all its attentions and precautions. With JNTO you will always be guaranteed the right distance, temperature detection in stores and places of interest, protections such as the mask. Safe, reliable and... absolutely dreamy.

You surely know the usual cities to visit, but this time we would like to show you other places that we particularly like. Are you ready? Start packing your bags for your dreamy and safe travels!

photo credits: viahero.com

Nagoya

Nagoya is a city in the Chūbu region of Honshū Island in Japan, with a port on the Pacific Ocean and two airports, including the new Chūbu-Centrair International Airport, which opened on February 17, 2005.

What to see in Nagoya

First and foremost, we believe the Atsuta Shrine is the most important. This shrine, founded over 1900 years ago is one of the oldest Shinto shrines in Japan. Here, for is kept the sword Kusanagi no tsurugi, one of the Three Sacred Treasures of Japan. This treasure, however, is not on display, but visible only to the emperor and a few monks. The shrine is located in a very serene forest to visit to relax.

Also, not to be missed is Nagoya Castle which was the residence of the Owari branch of the Tokugawa family, built in 1612 by order of Tokugawa Ieyasu. In spring and autumn, you can find a variety of flowers and plants absolutely unique in the world, are you curious to see them?

The Tokugawa Museum of Art is now where the residence of the Owari branch of the Tokugawa family once stood and collects and displays some of the family's great artistic heritage. The collection includes samurai swords and armour, costumes, tea ceremony utensils, books, maps and scrolls from the Genji Monogatari. Near the museum is a beautiful Japanese garden, the Tokugawa-en.

Osu Kannon Temple, on the other hand, is a Buddhist temple located in the centre of Nagoya. The temple houses a rich collection of ancient Japanese and Chinese texts.

Nagoya is home to very important museums, including The Railway Museum that exhibits ancient steam locomotives including the legendary C62 portrayed in the anime Galaxy Express 99 and the Toyota Museum of Industry and Technology that traces the evolution of manufacturing processes and aspects of industrial technology.

Kobe

photo credits: wallpaperflare.com

Kōbe is located on the island of Honshū. For about six months in 1180, it was the capital of Japan, when Emperor Antoku moved to Fukuhara kyō, which was located in today's Hyōgo-ku city district.

What to see in Kobe

A place not to be missed and enjoyed completely is the Shin-Kobe and Nunobiki Herb Garden Cable Car that starts near Shin-Kobe Station. On the way up, you'll pass by the Nunobiki Waterfall and Nunobiki Herb Garden but the focal point of the ride is at the observation deck located right next to the top station, which offers spectacular views of Kobe both day and night.

Also take a trip to Sorakuen Garden which was part of the residence of Kodera Kenkichi, former mayor of Kobe opened to the public in 1941.

Nostalgia for parks? Meriken Park is a mix of nature and modernity. Along with the greenery, you can range up to a collection of modern art installations. In this park, you can find the red harbour tower and the Maritime Museum.

The Kobe Museum was opened in 1982, with collections from the Kobe Archaeological Museum and the Namban Museum of the Arts. The museum's permanent exhibition offers a collection of maps from different regions and eras of Japan, as well as artefacts representing Japan's trade with foreign countries.

You can't leave Kobe before making more than a quick trip to the Arima Onsen, a famous spa town in a natural mountain setting. Your relaxation is assured!

Delight your senses, delight your eyes as well at the Akashi Kaikyo Bridge. At over 4 km long, it is the longest suspension bridge in the World. The bridge connects the island of Honshu to the island of Awaji.

In Kobe, we find a museum not to be missed, the Earthquake Museum. On January 17, 1995, at 05:46, the city of Kobe was hit by the Great Hanshin Awaji Earthquake, causing the death of over 5000 people and the destruction of tens of thousands of homes.

The museum, which opened as a memorial in 2002, includes a large theatre with a screen that plays realistic images of the earthquake's brutality, and various interactive games on disaster prevention.

To end our visit to Kobe, let's enjoy a visit to the Sake Distillery! The Nada district in Kobe is the major sake production site in the region, due to its good availability of high-quality rice, suitable water, and favourable weather conditions for producing the alcoholic beverage.

Sapporo

photo credits: suitcasemag.com/

Sapporo is a Japanese city, capital of the Hokkaidō prefecture, located in the southwestern part of the island of Hokkaidō, known for hosting the 1972 Winter Olympics, the first held in Asia, and for the famous Snow Festival that attracts over 2 million tourists from all over the world.

What to see in Sapporo

The historic village of Hokkaido

Of course, we start with the Hokkaido Historical Village, which is an open-air museum. 60 buildings from the past with various sections including towns and villages Don't miss these moments!

Instead, ìthe Sapporo Snow Festival (Sapporo Yuki Matsuri) takes place every February in Sapporo for a week. Born in 1950 when high school students started building snow statues in Odori Park, it is now a big event with spectacular snow and ice sculptures that attracts millions of visitors every year. In contrast, the Okurayama Observatory originated from the 90-meter ski jump used in the 1972 Winter Olympics! A must-see attraction, right in the Okurayama Ski Jump Stadium.

Want to relax after a long walk? Here for you is Moerenuma Park which is a park in the northeast of Sapporo surrounded by a swamp, a unique place that you definitely can't miss.

Here we are at the Hokkaido Historical Museum which documents the history of Hokkaido's development. You can find and see, in chronological order, the entire history of the prefecture from 20,000 years ago, to the post-war years after 1945.

Hungry? Shiroi Koibito Park is a chocolate company. Have you ever tried the Shiroi Koibito cookie? In case you've never tried it, it's two thin butter cookies with a layer of white chocolate in between. This is one of the top souvenirs in Hokkaido!

Thirsty? After chocolate, a good beer suits us perfectly, so we recommend the Sapporo Beer Museum.

In Japan beer was born in Hokkaido in fact, Sapporo is one of the oldest and most popular brands in the country. This beer is produced, precisely in Sapporo, in 1877 and is famous throughout the world, you will have happened to find it in restaurants here in Italy! The museum will show you the production process of beer and not only that! You can end the visit with a unique tasting!

Our visit ends in relaxation in the Botanical Garden that has a mainly didactic purpose, apart from being a pleasant break for visitors. In our opinion absolutely not to be missed, especially if you are looking for a moment of peace during the excursions and visits.

Kamakura

photo credits: japan-guide.com

This is a very important place that we at Japan Italy Bridge absolutely recommend. We are talking about Kamakura, a tourist and also seaside resort easily accessible from Tokyo. If you need a moment of relaxation during your trip to Japan, you can count on Kamakura.

Just think that Kamakura is facing the ocean, with its beach about 2 km long that takes two different names, Yuigahama Beach and Zaimokuza Beach. All around are hills and forests, crisscrossed by various trails. Among these is the Daibutsu path that leads from the great buddha to the Kita-Kamakura station, the Genjiyama path that starts from the Jufukuji temple and connects to the Daibutsu path, about at the height of the Zeniarai Benten temple, the Gionyama path near the Myohonji temple and the long Tenen path that connects the Kenchoji temple to the Zuisenji and Jomyoji temples.

During the Heian period it was the capital of the Kantō region and in 1192 the shogun Minamoto no Yoritomo moved his new capital here, transforming Kamakura din a real political centre of Japan.

What to see in Kamakura?

Kamakura is mainly known for its temples and altars and the one that we loved the most perhaps because of the bond that we feel towards this family of Samurai, is the shrine Tsurugaoka Hachimangu. The shrine is dedicated to Hachiman, the patron god of the Minamoto family and Samurai in general. On a terrace at the top of a staircase you can find the main hall with a small shrine museum, which displays various treasures such as swords, masks and documents. Next to this grand staircase, you could find a beautiful gingko tree that delighted visitors' eyes with its golden color every autumn, which unfortunately did not withstand a storm in 2010. Before entering the staircase, you can find the Maiden, a stage for dance and music performances.

The large statue of Amida Buddha, on the other hand, is located in the Kōtoku-in temple and is the most important statue in the country. Think that the temple in which it was located was destroyed during a tsunami in the fifteenth century, but the statue resisted and since then it is outdoors. The town is also home to the tombs of Minamoto no Yoritomo and Hōjō Masako. Engakuji Temple is one of the main Zen temples in eastern Japan, founded by the ruling regent Hojo Tokimune in the year 1282.

We move on to Hasedera Temple famous for its eleven-headed statue of Kannon, the 9.18-meter-tall goddess of mercy. The Kannon museum displays some of the temple's treasures, including Buddhist statues, the temple bell and a scroll. Also beautiful is the location of this temple, built along a wooded hillside quilted with small lakes.

As we said, Kamakura is the place of temples and shrines, so we point out other names to visit: Kenchoji, The Zeniarai Benten (very important for tradition if you want to wash your money!) and Zuisenji.

Obviously, there are restaurants where you can taste the delicacies of the place.

Hakone

photo credits: gaijinpot.com

Another must-see destination in Japan, in our opinion, is Hakone. Easily accessible from Tokyo, it is a place that can offer you not only relaxation, but also unmissable experiences. Here is our virtual tour of Hakone!

What to see in Hakone

The first thing to see is definitely Lake Ashi. We left our hearts on that lake and the panoramic view of Mount Fuji in the background. A real picture that you will carry inside you for a lifetime. This picture is among other things one of the hallmarks of Hakone. To experience Lake Ashi in all its beauty, you can cross it thanks to three vessels inspired by the ships of the eighteenth and seventeenth centuries. Special views, the important ports of Hakone, Machi and Porto Moto will make your moments unforgettable and you will feel part of that unique picture.

Always in the name of relaxation, remember that Hakone is the city of Onsen or hot springs. Today of the wonderful thermal centres, these Onsen will offer you the heavenly moment of relaxation, pampering all your senses. The Yumoto spring is the oldest and is located near Odawara. You are spoiled for choice, among the names we recommend is definitely Hakone Kamon, with its pools made externally of wood and stone.

After relaxing, it's time to visit the Hakone Shrine, Hakone Jinja which is located right on the shores of Lake Ashi. It consists of many buildings scattered in the forest, with a staircase embellished with lanterns that will make the walk a fairy tale.

Let's move on to the wonderful Odawara Castle built in the mid-fifteenth century in the hands of the Hojo Clan. We are in 1950 when Toyotomi Hydeyoshi defeated the Hojo Clan and reunited Japan. This castle is rich in history, three stories high seen from the outside and four inside. Inside the castle, you can see valuable period furnishings, armour and other items of historical interest and if you really want to enjoy a spectacular view, look at the whole city from the other in the highest floors! For Museum lovers, here is the Odawara Castle Historical Museum, with a very interesting interactive exhibition of objects related to the history of the castle.

On the other hand, the Gora Park is a French-style park with a large fountain, a rose garden and two greenhouses with tropical plants and flowers, a restaurant, a tea room and a Craft house, where you can try various workshops such as pottery making, glass blowing and ikebana composing.

After all that, what to do to extend your life? I'm not kidding, but I'm talking about Owakudani's black eggs. We are in a volcanic area famous for kuro tamago chicken eggs made black by cooking in hot springs. According to Japanese tradition, if you eat kuro tamago you will extend your life by 7 years! You will find them only in Owakudani!

Viaggiare il Giappone in sicurezza

Obviously, these are just some of the places that we propose, but Japan should be seen all. Each temple, each shrine, each garden is a world unto itself, something that cannot be found in other parts of the world. If you want to experience many different worlds in one place, you can't do without Japan. Thanks to JNTO, you can have a personalized and safe trip! With JNTO, especially in this moment of pandemic for COVID-19, you can explore Japan in absolute safety, visit the places you love without fear and in complete tranquillity. We like to repeat that with JNTO will always be guaranteed the right distance, temperature detection in stores and places of interest, protections such as the mask. Safety first and no risk, to enjoy a trip with a capital V do not be afraid and rely on JNTO! We have done it several times and we can assure you that the experience will be not only unforgettable but also in complete safety!

Also in collaboration with JNTO, don't forget the Hiroshima Hakken menu at TENOHA Milanoa! While waiting to leave, you can enjoy Hiroshima's specialties with this special TENOHA menu sponsored by JNTO Japanese National Tourist Board! This special menu that, with its sake tasting, will keep you company throughout January! The best sake in Hiroshima is here!

Night Emperor, Honshu ichi, Zoka, Itteki Nyukon, Sempuku Shinriki are the sake from Hiroshima that will remain available for you all January with the Sake Tasting! Here are their characteristics:

Honshu ichi

Night Emperor, Honshu ichi, Zoka, Itteki Nyukon, Sempuku Shinriki are the sake from Hiroshima that will remain available for you all January with the Sake Tasting! Here are their characteristics:

‘Zoka’

Junmai Daiginjo is made from "Yamada Nishiki" sake rice grown in a field located about 6 km north of the brewery, using Saijo underground water and the Hiroshima Mori technique. The delicate aroma and sweetness of the transparent and gentle rice harmonize perfectly with the fresh acidity. You can enjoy it cooled with a thin cup or glass of wine. Sake certified with Saijo JAPAN brand)

Itteki Nyukon

This sake has as first material the rice suitable for its preparation. A slightly dry Junmai Ginjo sake that goes well with foods with the right acidity, good both cold and hot.

Sempuku Shinriki 【Nickname】Filled with happiness

Kamiriki rice, which is the origin of Chifuku, is 85% processed and is close to the processing speed of rice from the Meiji and Taisho eras. A bottle full of feelings for the preparation of sake, especially suitable for people who particularly care about Japanese sake.

Night Emperor

Night Emperor is a mixed Hachitan Nishiki based liqueur produced in Hiroshima Prefecture. Versatile liqueur is easy to combine with any dish. Soft taste that takes advantage of the characteristics of fresh water preparation and keeps the alcohol content low while maintaining the taste of koji and rice. Good tasted both cold and hot.

Start planning your trip to Japan and while you're doing it, enjoy the special Hakken of Hiroshima at TENOHA Milano for the whole of January! As you can see, JNTO is close to you at all times, reminding you that Japan is a destination that will give you all the security you are looking for!

Japan History: Ankokuji Ekei

Although Ankokuji Ekei (1539 - November 6, 1600) was a member of the Aki Takeda clan, his year of birth and his father are still uncertain. His year of birth varies from 1537 to 1539 and whether his father could have been Takeda Nobushige or Takeda Shigekiyo.

Ankokuji Ekei, samurai, monk and diplomat

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: samurai-world.com

When the Aki Takeda were destroyed in 1541 by Mori Motonari, Ankokuji Ekei was taken to a safe place in the temple of Ankokuji, which was located in the province of Aki.

At that time, Ankokuji Ekei changed his life becoming a Rinzai Buddhist monk and also a diplomat of the Mōri clan. It was the year 1585 when Toyotomi Hideyoshi praised his negotiations when the Mori clan formally served Hideyoshi. As Hideyoshi's advisor, he even received a feud of 23,000 koku in Iyo province as a reward after the invasion of Shikoku (1585).

In 1586, after the Kyushu Campaign, his possessions were expanded to 60,000 koku. He participated in the war of Imjin, the Siege of Shimoda and lost the battle of Uiryong against Gwak Jae-u.

Despite being a great priest, Ekei led the men for both Hideyoshi and Môri Terumoto. Ankokuji Ekei was present at the Siege of Shimoda in the Odawara Campaign (1590) and in the Korean Campaigns (1592-93, 1597-98) in Terumoto's staff.

In 1600 Ekei joined Ishida Mitsunari and exerted considerable pressure on Môri Terumoto, eventually prevailing on the advice of Kikkawa Hiroie. In the battle of Sekigahara, Ekei commanded 1,800 men on Nangu Hill, positioned near the troops of Hiroie and Natsuka Masaie. When the main armies were engaged around the village of Sekigahara, Ekei and the troops of Môri (commanded by Môri Hidemoto) decided to enter the fray and waited for Hiroie, the vanguard of Môri, to move. Unbeknownst to them, Hiroie had negotiated a secret agreement with Ieyasu and had no intention of moving.

Ekei and the Tokugawas

Ekei and Natsuka had no intention of doing anything so the 25,000 soldiers under Môri command remained inactive. This inactivity sealed a defeat that became devastating after the betrayal of Kobayakawa Hieaki, and once the matter was clearly decided, Ekei and his comrades thought it was better to retreat in a hurry.

Ekei tried to flee to To-ji, but was captured according to legend by a rônin who had an old grudge against him. Tokugawa sentenced him to death on Kyoto's Rokujo-ga-hara, and was beheaded together with Konishi Yukinaga and Ishida Mitsunari.

Jidai Matsuri

The Jidai Matsuri ( 時代祭り, literally "The Festival of Historical Epochs"), celebrated in Kyoto on October 22 of each year. This festival represents a magnificent opportunity to experience over a thousand years of Japanese feudal history as direct spectators in a single day.

Jidai Matsuri, the Festival of Historical Epochs

Guest Author: Myriam

photo credits: travel-on.planet-muh.de

The origins

This festivity has its roots in the oldest history of Japan and recalls, through an impressive historical costume parade, the events and characters that have marked the life of the city since its foundation. It has been held since 794 by Emperor Kanmu (桓武天皇, Kanmu Tennō) until the transfer of the capital to Edo in 1868 by the decision of Emperor Mitsuhito.

Since its creation under the name of Heian Kyo (平安京, "capital of tranquillity and peace"), Kyoto has remained the capital of Japan almost uninterruptedly for over a thousand years. With the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the beginning of the Meiji Era, the entire imperial court was transferred to Edo, which became Tokyo (東京, literally "eastern capital").

In 1895 on the occasion of the 1100th anniversary of its foundation, the governments of the city and the prefecture of Kyoto established the Jidai Matsuri with the intention of restoring lustre to the ancient capital. Along with this, the aim was to honour the memory of the emperors Kanmu and Komei through the construction of the majestic Heian shrine.

A thousand years of history on the road

photo credits: fodors.com

Since then, on October 22 of each year, Jidai Matsuri brings back to life the splendour of feudal Japan. This allows residents and tourists to relive the life of the ancient capital for a few hours. Today, the main attraction of the festival is the Jidai Gyoretsu. It is a historical parade in which over two thousand participants take part, dressed in period costumes or in costumes meticulously reproduced by the craftsmen of Kyoto.

At the head of the parade are the mikoshi (portable sanctuaries) dedicated to the Kanmu and Komei emperors and the festival's honorary commissioners, on horse-drawn carriages in the style of the mid-19th century and from there the parade unfolds in reverse chronological order, from the Meiji Era to the Heian period, through about twenty thematic groups, which make it possible to rediscover, era after era, the characters who contributed to the history of the city, from simple peasants and soldiers to prestigious historical figures, such as the unifiers of the country Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, or figures of religious or cultural importance, such as Murasaki Shikibu, author of the famous "Genji Monogatari". The figures are accompanied by the music of drums and flutes, which together with the over 12,000 historical artefacts used, allow spectators to immerse themselves completely in the atmosphere of past eras.

photo credits: blog.halal-navi.com

The long procession leaves at 12.00 noon from Kyoto Gosho, the imperial palace. It then winds for hours through the streets of the city centre, touching the most evocative and significant places. We see it passing by Oike and the Okazaki district, finally reaching the Heian Sanctuary. Here the Festival ends with the ceremonies foreseen by the Shinto rite.

Nada no Kenka Matsuri

From October 14th to 15th of each year, in the Matubata Hachiman Shrine (松原八幡神社) in the city of Shirahama in Himeji, Hyogo Prefecture, the Nada no Kenka Matsuri (灘のけんか祭り) one of the biggest autumn festivals in Japan is held.

Nada no Kenka Matsuri, Fighting for blessings

Author: Sara

photo credits: armidaleexpress.com.au

The term "kenka"(けんか) contained in the name of the Festival means "to fight", for this reason, in the current language, it is defined as "the Festival of the fight" in which the Kami (the gods) will bless the winner of the fight with a good harvest. Given the impetuousness with which it takes place, only high school boys and men up to the age of 45 can participate in the event according to Shinto tradition. In addition, participants must belong to 7 specific villages: Higashiyama (東山), Kiba (木場), Matsubara (松原), Yaka (八家), Mega (妻鹿), Usazaki (宇佐崎), Nakamura (中村).

October 14: The Eve "Yoi-Miya" (宵宮)

photo credits: armidaleexpress.com.au

At 11:00 am everything is ready for the "Neri-dashi" parade (練りだし). The 7 Yatai (small sacred floats) from the 7 villages go to the Matubata Hachiman Shrine to receive the divine blessing, "Miya-Iri" (宮入). Here the Yatai compete in the first competition called "Neri-Awase" (練り合わせ), competing against each other. A sort of "preparation" because the real "fight" will take place the next day and will be even more difficult. At this point, the "Shishimai" takes place: a dragon dance in front of the elementary school of Shirahama.

October 15: Hon-Miya the heavy Yatai clash

photo credits: diversity-finder.net

The main event of the Festival starts at 5:00 am. The lion of the village of Matsubara (松原の獅子) celebrates the dragon dance at the Sanctuary to worship the gods. Afterwards, the ceremony moves to the ocean where the participants of the villages eliminate their impurities of the spirit by bathing in cold water (Osogi 禊). At this point, the Miya-Iri (opening ceremony) at the Matubata Hachiman Shrine is started with the blessing of the gods. At last, the thinking confrontation begins: the first are the 3 Mikoshi (the least expensive portable sanctuaries of the Yatai) of the village in charge of hosting the festival (every year the place changes alternating between the 7 villages).

The first Mikoshi (一の丸) is very heavy and is carried by men over 36 years old. The second (二の丸) is a bit lighter and is carried by men between 26 and 35 years old. The third Mikoshi (三の丸) is very light and is worn by men under 25 years old.

They fight each other twice (神輿合わせ, mikoshi-awase): first in front of the main building of the Sanctuary, then in the battlefield at the foot of Mount O-Tabi-Yama (御旅山). At the end of this clash, it is the Yatai's turn on the battlefield (Neri-awase 練り合わせ).

photo credits: kabegami.image.coocan.jp

The excited cries of spectators and participants make the event particularly lively and full of passion. At the end of the battle, the 3 Mikoshi and 7 Yatai are taken to the top of the mountain where prayers are said. the Nada no Kenka Matsuri ends with the descent from the mountain which will take place in the same order in which the villages have climbed.

Fuji san, a deep focus on the symbol of Japan

Snow-capped peaks, dizzying slopes, harmonious and perfect shape: Mount Fuji. Breathtakingly majestic, a famous cultural icon: a mystical and spiritual place. There are no words to describe what it feels like to be in front of this wonder of nature. Its importance is such that it is often said that, more than a symbol of Japan, it is Japan.

Mount Fuji 富士山 The symbol of Japan

Guest Author: Flavia

Fuji (富士山 Fu-Ji-San) is located in the Chūbu region (中部地方), about 100 km southwest of the capital Tokyo. It lies between the current prefectures of Yamanashi and Shizuoka, with Kanagawa prefecture to the east. The entire area is part of the Fuji-Hakone-Izu National Park (富士-箱根-伊豆-国立公園Fuji-Hakone-Izu Kokuritsu-Koen). Together with Mount Tate (立山) and Mount Haku (白山) is part of the CDs. Three Sacred Mountains ( 三霊山 San-Rei-Zan ) so identified because they are sacred to the Japanese tradition.

The numerous cultural-historical sites around the mountain testify to the great spiritual significance that has always been attributed to it. In pre-modern times it was, in fact, a pilgrimage destination for monks engaged in spiritual research and self-discipline, as well as for ordinary people.

Today this religious connotation has been lost. Although the idea is still widespread that climbing to the top of Fuji at least once in a lifetime is almost a religious duty. Nowadays, climbing is also facilitated by modern means, thanks to which the route to be made on foot is more than halved!

Source of inspiration for a vast cultural production (literature, poetry, art...), its influence has reached the West. It is now well known how much the prints of the masters Hokusai and Hiroshige, portraying Fuji, influenced Monet and Van Gogh.

The fact that it appears among the yen bills and in the name of the main television station is indicative of the central role it plays for the people of the Rising Sun. So much so that it is classified as a "Special Site of Scenic Beauty" and protected as cultural property by the Agency for Cultural Affairs (branch of MEXT). In 2013 it is declared World Cultural Heritage by UNESCO. It is included in the category culture - rather than nature - because its impact goes far beyond its natural essence. There are at least twenty-five sites of interest recognized by UNESCO, on Japan's most important mountain.

photo credits: expedia.it

Fuji Geological History

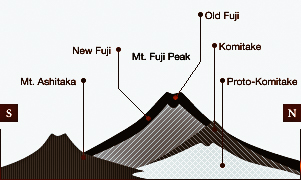

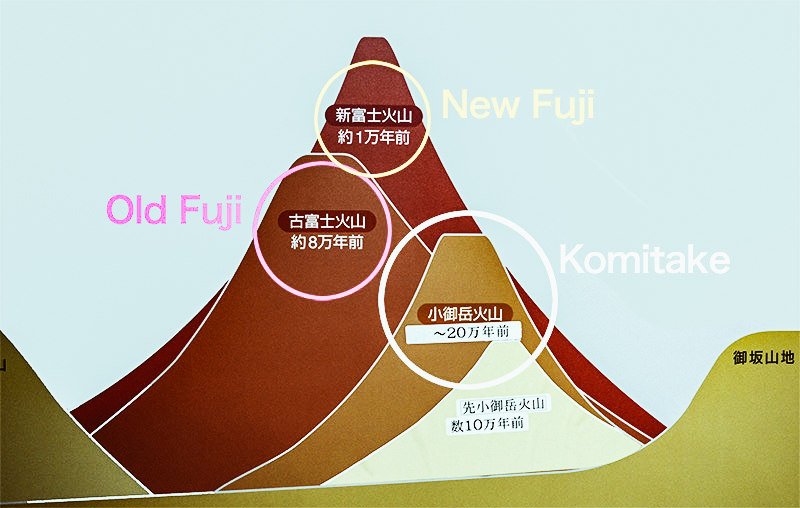

Fuji is classified as a stratovolcano, a volcano formed by the accumulation of layers of solidified lava and volcanic ash. Its particularly steep slopes, its perfect conical and symmetrical shape are the results of this overlapping process. It has a crater with a diameter of about 600 meters, 250 meters deep, and at least 70 small secondary peaks including Mount Hōei and Omuro. Its volcanic activity began more than 100,000 years ago.

It was long agreed that there were three stages of the stratification process, called "Small Peak" (小御岳Ko-Mitake), Old Fuji (古富士Ko-Fuji ) and New Fuji (新富士Shin-Fuji). Since 2004 new studies and explorations have revealed the existence of a fourth phase Proto-Komitake (小御岳 Sen-Komitake). It is currently believed that the Komitake originated as a result of eruptions produced by the Proto-Komitake hundreds of thousands of years ago. Just as about 100,000 years ago an eruption of the Komitake gave rise to Old Fuji, the summit of which reached about 2,700 meters with subsequent eruptions. So the Fuji over the millennia has been gradually shaping itself. It reached its present form about 10,000 years ago, after Old Fuji and Komitake also disappeared under the layers of lava.

It erupted nine times between 781 and 1083, and then it remained quiet for a few centuries. Its last eruption - which formed Mount Hōei - dates back to 1707, which for a while led to classify it as dormant. But around 1960 there is a change of definition: it is defined as "active" every volcano whose eruption has ever been documented. In 2003 a further update extends the definition to every volcano that has ever erupted in the last 10,000 years and that continues to give signs of activity. Under these last two designations, Fuji is now considered active. It ranks at 5 in the Volcanic Explosivity Index on a scale from 0 to 8 (like our Vesuvius and Etna).

photo credits: web.archive.org

Geography and territory of Fuji San

Thanks to its 3,776 meters of height, our Fuji is undisputed as the highest peak in Japan. However, between 1895 and 1945 it was climbed by another mountain! How? Because of the post-war agreements closing the first Sino-Japanese conflict, with the Treaty of Shimonoseki, when Taiwan came under Japanese control. Therefore, formally, in those years Taiwanese territory was Japanese. Thus, the Taiwanese "Jade Mountain" (玉山 Yu-Shan) - then called by the Japanese "New High Mountain" (新高山Nii-Taka-Yama) - with its 3,952 meters manages for 50 years to overtake Fuji-San.

There are three towns on its slopes (whose names also characterize three of the main access routes to Fuji): Gotemba (御殿場) to the east, Fujinomiya (富士宮) to the south-west, Fujiyoshida (富士吉田) to the north.

Five, the lakes (富士五湖 Fu-Ji-Go-Ko) that surround it: Yamanaka (山中湖); Kawaguchi (河口湖); Saiko (西湖); Shōji ( 精進湖 ); Motosu (本栖湖). Curiosity: the latter in particular would be the Japanese version of Loch Ness. Legend has it that in 1970 they sighted a creature of 30 meters with rough skin and full of humps: it was promptly christened Mossie!

Near the lakes, to the north-west, we also find a forest of 3000 hectares: Aokigahara (青木ヶ原), also known as Jukai (樹海) or "sea of trees" (sadly known for the primacy of suicides, second only to the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco). The area is also rich in caves and hot springs.

Mishotai (御正体山) and Shakushiyama (杓子山) in the northeast, Kurodake (黒岳) in the north and Kenashi (毛無山) in the west, are the closest peaks from which you can see Fuji in the front row.

photo credits: itinari.com

Fuji, etymology and meanings: But what does "Fuji" mean?

The first thing to note: the name "Fuji" already existed before the introduction of Chinese ideograms or sinograms. The characters used to indicate it were therefore chosen according to their pronunciation so that the latter would coincide with the pre-existing pronunciation. Written as it is today, i.e. 富士山 (Fuji-San), it is given the meaning of "Prosperous Mountain".

There are, however, different opinions that in the past "Fuji" meant something else. Everything always depends on the writing: the same pronunciation can correspond to more than one meaning. Ergo more words, distinguishable at that point from the writing (as well as the context).

Here are the most popular theories about the meaning of Fuji:

- Unparalleled Mountain【不二山】: very popular is the theory that the name of the volcano was originally written with these Kanji-ideograms- to mean "Unrivaled Mountain" (二 is the number two, so "not two").

- Monte dell'immortalità【不死山】: This interpretation is based on three works of the past: the ancient Chinese chronicles "Shiki" (史記), the Taketori Monogatari (竹取物語) and the Fuji Sanki (富士山記). The first reports the existence of an elixir of immortality on top of the volcano; the third describes the mountain as the home of immortal beings. The fire of Fuji so metaphor of the inexhaustible "fire" of life. The Taketori Monogatari suggests another etymology, however, that of "mountain rich in warriors" (富 = abundance, 士 = warrior).

- Winterless Mountain【不尽山】: Many people bring back such "inexhaustible being" to the snow because the summit is almost perpetually covered with snow.

These are still theories but, I must say, this last interpretation would be quite precise. Personally I do not disdain even the alternative of the "Mountain without equal", it is certainly right!

The misunderstanding "Fujiyama"

Speaking of Fuji names, it seems necessary to open a parenthesis on the issue "Fujiyama". If only for those who do not know the language. Since it has escaped the pen of its first transcriber, you might also come across this term in some tourist guides. Well, this is a linguistic misunderstanding! An error dating back to the first transcriptions from Japanese to Western languages.

The character 山, which indicates the mountain, is pronounceable with the Chinese reading "san" but also with the Japanese reading "yama". The Chinese reading (on'yomi) is clearly due to the fact that the ideograms come from China. The reading of Chinese origin is mostly taken when you have compound words, otherwise, the Japanese one (kun'yomi) is used. The exceptions are not rare, but Fuji is not among them.

That's why using "Fujiyama" as a translation of "Mount Fuji" (富士山) is an error. 山 " 山 " alone can be read "yama", but next to the name "Fuji" takes the pronunciation "san". Therefore, "Fuji-San" is the only correct pronunciation for 富士山 [Mount Fuji].

If ever, the form "Fuji no Yama" (富士の山 "Fuji mountain") would be admissible since 山 and 富士 are divided by the specification particle の. Actually there is also this expression, but it is obsolete, found in ancient literary works. Some also recognize the possible contraction of this rare term from "Fuji no Yama" to "Fuji-Yama". Even if it was, the eventual absence of the particle の assumes the presence, however, as much as it is understood. This is not the case in the wrong transcription "Fujiyama", where nothing is contemplated between "Fuji" and "Yama". Then, the latter is always an error.

Other courtly or disused versions are:

- Fu-Gaku (富岳 "Abundant Top");

- Fuji no Takane (富士の高嶺 "High peak of Fuji");

- Fuyō-Hō (芙蓉峰 "Lotus Summit").

photo credits: kyuhoshi.com

The sacredness of the mountains in the Japanese tradition

Mountains and volcanoes have always had a special place in Japanese spirituality, which has given them a special meaning since the beginning. They are seen as mysterious places, home to spirits as good as bad. A mountain or a volcano is definitely a special, sacred place. A deity, or the seat of one or more gods, perceived by the people as the protector of the whole community.

This autochthonous sensibility - pre-existing to Buddhism - was a form of shamanism that resulted in those beliefs and practices that constitute Shintoism. Shintō made nature an object of worship as an earthly manifestation of the Kami (神 Divinity). Not only the mountains but also the rocks, trees, rivers and waterfalls, lakes...all are perceived as the earthly expression of the Kami. Fuji for example is also defined in Shintō as "Yama no Kami" (山の神).

This Shintō practice of mountain veneration is part of the Kannabi Shinkō (神奈備信仰 "Kannabi Faith"). Kannabi" are all those sacred places used to celebrate and give thanks to the Kami; in the case of mountains, the gods or spirits of the mountain.

This autochthonous conception is then intertwined with the Buddhist vision of the mountain as an ascetic place for the search for enlightenment and the realization of Buddhism; the Taoist one, of the mountain as a mystical place, of Yin-Yang harmony and the five elements; the Confucian one, of the mountain as a cosmic place that connects all living beings in the common search for harmony and self-realization (not in a selfish sense, of course).

photo credits: tripadvisor.com

The ancient faith Fuji: why worship a mountain?

The question is very simple but full of meaning. The Japanese have always looked at Fuji - at nature in general - with the eyes of a child, I dare say. With attention to its behaviour, reacting and adapting their actions accordingly. To begin with, and before anything else, this "looking", alone, is distinctive of the type of approach that distinguishes these people. Then comes into play as they have observed, that is, with attention. Which brings us to step three: their response after what they have caught. An answer as pertinent as the initial, careful, observation. An answer that communicates nothing else but the acknowledgement "I have recognized you, I have recognized your existence; I respect your will". Only a careful perception could lead to this kind of response.

So think of Fuji, so imposing, so perfect...and so explosive in ancient times: the ancient Japanese could only be impressed by such a manifestation. The first settlements of which there are traces are very ancient: they date back to a period between 11,000 and 13,000 years ago, called Jōmon Incipiente (very first Japanese prehistoric era). Well, among other things, stones have been found, whose arrangement indicated unequivocal ceremonial signs!

Its power, together with its grandeur, led the ancient Japanese to fear it and admire it at the same time. They came to the conclusion that that volcano so powerful had to be the expression of a deity or just a deity (神Kami). For obvious reasons, they tended to consider it a deity of fire. So the Fuji began to be worshipped with the intent to avert its eruptions, inevitably interpreted as the wrath of the deity present there.

The nature of this ancient autochthonous faith remains, in any case, a little mysterious, but it should not be surprising. After all, we are talking about really ancient times.

Fire and Water: the dualism of Fuji-Kami

.

One thing, however, that can be seen with more confidence is that double attitude/reaction of admiration and fear on the part of the ancient Japanese. Despite its smoky character - pass me the term - of the time, Fuji was not perceived as a mere intractable or evil divinity. It was simply what it was. And the Japanese ancestors also considered its positive aspects...almost all of them converging in a single word: water.

In ancient times the water of Fuji has in fact represented an important source of sustenance for the inhabitants of the surrounding areas as well as for the fauna and flora. Suffice it to say that the abundance of water - and food - was considered a valid reason to want to continue living near the volcano, despite the danger it represented.

Even today the abundant rainfall and snowfall that is poured every year are decisive for the maintenance or formation of rivers and springs underground. And even today the water of the mountains - and the mountains themselves - are seen as a source of fertility (think of rice crops). Moreover, the water of Fuji was also considered sacred, so much so that it was later used for ablutions and purifications for religious/spiritual purposes.

Fuji was therefore seen in a twofold way as fire and water-vulcano and spring, divinity of fire and at the same time source of purification. Fear and respect for the power of the volcano: simply two sides of the same coin. Duality, in truth, is a characteristic of this people (it is found in history, in language...). Apparently, not even Fuji is exempt from it!

photo credits: matcha-jp.com

Sengen-Asama Sanctuaries

The wrath of the divine-Fuji was very frequent between the end of the 8th and mid-10th century. Thus, around the ninth century, the sanctuaries dedicated to it began to sprout like mushrooms, not only on the slopes of the volcano, but throughout the archipelago. We talk about Asama or Sengen (浅間) sanctuaries when it comes to the god of Fuji (浅間の大神Asama/Sengen no Ōkami). The terms Asama and Sengen are only two different readings of the same word. However, while "Asama" can also be found in other mountains, "theengen" ends up identifying all the Fuji sanctuaries of worship, particularly those on its slopes.

It is often read that the Kojiki (古事記) - "Tales of ancient events" - associates the divinity of Fuji to the figure of the goddess Kono Hana Sakuya Hime (木花咲耶姫). According to the myth, the goddess "Princess who makes the trees bloom" is said to descend directly from Izanami and Izanagi, the original creator gods of the Japanese archipelago. While it is true that the oldest Japanese narrative collection narrates about Sakuya-Hime and her father, the god Oyamatsumi (大山津見神 "mountain goddess"), the association to Fuji is not so obvious. In fact, the historian Byron Earhart - among the main sources of this article - warns that this link is actually recent. And that the Kojiki, in fact, would not make any direct connection between Fuji and the goddess.

In any case, it is in such Sengen sanctuaries that those rituals to prevent catastrophes caused by the volcanic god Sengen-Asama take place. In order to calm his anger, he is even given the title of Myōujin (明神 "Illustrious Kami") or "Illustrious Gods". The rituals consisted of rites of pacification and thanksgiving, accompanied by the reading of Buddhist sutras.

In this phase of the cult, however, Fuji is not yet climbed but rather venerated from afar. This is certainly due to the fact that around the 11th century its volcanic activity was still unstable. It is only with the inclusion of Esoteric Buddhism in this framework - and with the end of the eruptions - that religious pilgrimages will begin.

photo credits: livingnomads.com

Shugendō: where Shintō meets Buddhism

You can't talk about Fuji without talking about Shugendō. It is in fact this practice that significantly increases the popularity of Fuji through asceticism. Shugendō (修験道 "Via della Pratica Ascetica") is the encounter between Shintō tradition and Esoteric Buddhism. A hybrid between native shamanic practices and Buddhist rituality. This "hybridization" consists as much in a mix of elements of each tradition as in a coexistence of the same (some Shintō elements, for example, remain well intact).

The Shugendō takes shape towards the end of the Heian period (794-1185) but the "mountain" Buddhism of the Saichō and Kūkai ascetics of the Nara period is its precursor. As we know, around 1083 Fuji ceased its intense activity. Since then it began to be identified as a place of "apparition of the Buddhas": a place for all those seeking a spiritual path. This path is also understood in the true sense of the word, as witnessed by the spiritual pilgrimages that are becoming more and more a "phenomenon". The practitioners, mainly known as Yamabushi (山伏) or Shugenja (修験者), included different types of ascetics in addition to actual monks.

Its origins can be traced back to the semi-legendary figures of Prince Shōtoku (who would have inspired the above mentioned Saichō) and the mystic-ascetic En no Gyōja or En no Ozunu. Legend has it that both the prince and Ozunu reached Fuji in flight - just in Taoist magician style (仙人 Sen-nin). En no Ozunu is remembered as the legendary founder of Shugendō, the one who would bring rituals and ascetic practices to the mountains.

Shugendō is key because he elaborated and developed the mountain practice born in the Nara era, bringing it to Fuji. And making the latter popular as a place of spiritual asceticism. A fundamental element that characterizes it are the ascetic experiences of its main exponents and the insights they receive from it, determining the syncretization between Kami shintō and Buddhist divinities.

Murayama Shugendō, Matsudai and Raison

If En no Gyōja is the "legendary" founder of Shugendō, more historical are instead Matsudai (end Heian) and Raison (presumably end Kamakura). The two ascetics, which constitute the Shugendō linked to Fuji.

Matsudai, the "Saint of Fuji" (富士上人 Fuji Shōnin) - according to the chronicles the first to climb the mountain - is the one who inaugurated it as a place for ascetic practices. In 1149 he would in fact erected on its summit a first form of a temple dedicated to Dainichi Nyorai (大日如来 the "Great Sun-Buddha"). Thus operating a first syncretism between the divinity of Esoteric Buddhism and Sengen-Asama Ōkami. However, since, then as now, the conditions up there are impervious almost all year round, Matsudai places the base of the neo-movement on the slopes of the mountain. Precisely, in the village of Murayama (today's Fujinomiya)- hence the name "Murayama Shugendō". A complex of temples begins to rise all around the mountain. Since then, Murayama Shugendō becomes a movement of such magnitude that it exerts full control over the mountain (even collecting "tolls" for access to the summit).

But if Matsudai is the forerunner, it is the monk Raison who gives the movement a truly organized structure. Through the network of temples, religious practices and paths - "inaugurated" under Murayama -, Fuji becomes institutionalized.

It is said that Matsudai gives the movement the vertical structure while Raison the horizontal one. Raison opens the ascetic practice on the mountain also to ordinary people, establishing contacts with the so-called lay ascetics (行人 Gyōnin) and leaders of local groups. This already marks a small difference from Matsudai, at that time the movement was more linked to the court and the imperial family (and later to the feudal dominated class).

Raison's work is thus a forerunner to subsequent mass pilgrimages, but it also carries within itself the seed of the decline of the movement. Accomplice the advent of the Sengoku era, with the increase of flows towards the mountain, at a certain point Murayama Shugendō will no longer be able to control all the routes. The killing of the daimyō of Suruga, on which the movement rested, will be the final blow that will mark the sunset of Murayama.

photo credits: yamabushido.jp, mundo-nipo.com

Fuji-Ko ( 富士講 ), Kakugyō and Miroku

It is, therefore, the interweaving with politics and the ruling classes that drags down the Murayama Shugendō. Also because, the new times required new responses to the new historical paradigms that were occurring. We are in the Sengoku era (戦国), the hard era of the Warring States: an era marked by hunger, general disorder and terrible battles, where nothing was stable. In the context of these dramas, people needed new answers. It is at this juncture that those religious groups known as Fuji-kō originated (富士講). "Confraternities" that were inspired by the popular cult inspired by Fuji and that identified Fuji as their place of worship. The emphasis on the inclusion of all social classes is what distinguishes Fuji-kō from Murayama Shugendō.

It is in this frame that the figures of Kakugyō and - a little later - Jikigyō Miroku (1671- 1733) come into play. Kakugyō with his activity further increases the fame of Fuji, making many ordinary people come to the mountain, going to form such associations (講). Miroku does the same thing, however, with a ritual suicide act on the mountain, which puts Fuji even more in the spotlight. For this reason, both of them are considered inspiring the popular Fuji-kō cult.

The experience of Kakugyō circumvents the Murayama tradition, becoming separate from that of Matsudai and Raison. The revelations he would first receive from the spirit of En no Gyōja and then from the syncretized divinity of Fuji Sengen-Dainichi are fundamental. He would have been revealed that Mount Fuji and its divinity would be the source of all that exists. That all the suffering of that period was due to an imbalance between heaven and earth. And the way to remedy it, that of unifying the Fuji faith in a "cosmological" system of beneficial practices open to all people. From this follows the mission of Kakugyō, to unify practices and beliefs related to Fuji as the basis of the popular cult of Fuji-kō.

The activity of Kakugyō is characterized by purifications and ablutions in the lakes around Fuji. As well as the ascetic practices in the Hitoana (人穴), the caves of the volcano indicated by the essence of En no Gyōja in the first revelation, where he would then "come into direct contact" with the Sengen-Dainichi.

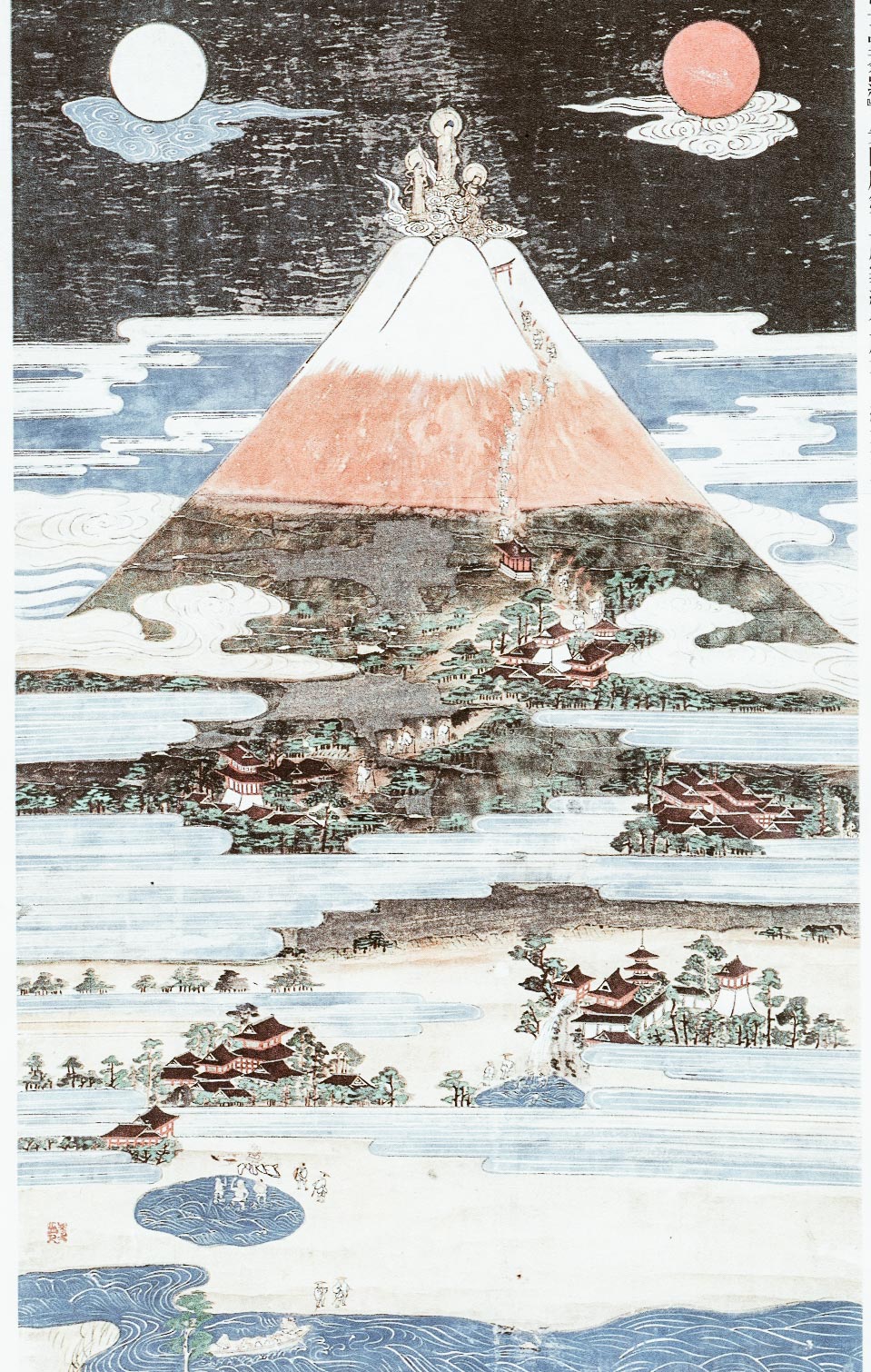

Fuji Mandala

Yes, even in Japan there were mandalas! Originally from India, and passing through China, through Buddhism they also came to the Land of the Rising Sun. We want to remember them, because they were a characteristic and functional tool for Esoteric Buddhism of the Muromachi era. His practitioners used them to reach the understanding of Cosmic Truth and as a support during meditations.

Such mandalas represented the universal order of things-the essence of which is Buddhism and the relationship between it and its earthly manifestations. To embrace this truth in words alone was not considered sufficient and, for this reason, it was recognized in iconographic language as the best way to internalize it. The image, more than the word, seems to be the preferred tool of this people to get in touch with the essence of things. After all, even ideograms, what are they if not images?

Specifically, the Fuji mandalas represent the ambivalent path of the pilgrims - that is, the geographical and spiritual path they decided to take. Typical of this era, the representation of the three peaks of Fuji associated with the triad of Buddhist deities Dainichi, Yakushi and Amida (as well as the Isshin Sangan doctrine 一心三観). So popular was it, that the three peaks became a custom of Fuji iconography. Without prejudice, of course, to the normal variations characteristic of all times.

photo credits: medium.com/@jamesinjapan/

Meisho (名所): the Fuji in the arts

The meisho ("famous locality") are those places sculpted in the collective imagination because they were made famous by the Japanese arts. They are a reflection of that special relationship with nature from which the Japanese have always drawn inspiration. Nature is associated with moods and the image is the best way in which this people can give voice to their innermost feelings. Seasons, rhythms and colors of nature, places...become so essential, in their specificity, to express moods otherwise difficult to describe in words. The attention to nature is thus expressed through an aesthetic sense that transcends the very representation of the "object".

This tendency can already be seen in the Nara period (8th century), when the written tradition had not yet fully established itself. It is from this period the poetic anthology Man'yōshū (万葉集 "Collection of ten thousand leaves"). The Man'yōshū speaks of Fuji as a "mysterious" god, with "burning fires"; he paints it as an ideal mountain and highlights its importance as a protective deity. That one of the very first written works speaks to us immediately about Fuji is indicative. It means that the mountain was somehow "installed" in the collective imagination, like meisho, even before the passage to the written tradition! And this even though at that time it had not yet emerged as an absolute icon (although kami, it was still "only" one of the many existing sacred mountains).

Around the thirteenth century it began to become markedly more protagonist. In the Muromachi period it became central both as a religious subject (as in the Fuji Mandalas) and as a purely landscape icon (ink paintings in Chinese style). Among these, the "Eight Fuji Views" marked the beginning of Fuji's serial representations, inspiring in the Edo period the masterpieces of the masters Hokusai and Hiroshige.

Other famous works in which Fuji appeared: Literature Taketori Monogatari (竹取物語) and Ise Monogatari (伊勢物語) both from the 10th century; novels by contemporary writers Natsume Sōseki and Dazai Osamu. Visual Arts The 11th century Shōtoku Taishi Eden/Emaki paintings on roll; the Ukiyo-e woodcuts by Hokusai and Hiroshige from the 18th-19th centuries; and, of course, photography and cinema in modern times.

Climb Fuji to the present day

There are four possible access routes or routes to the summit. In ascending order of altitude:

- 1450 m, path Gotemba - the longest of all, without medical care centers, is not very popular;

- 2000 m, Subashiri trail - less popular and, perhaps because of this, devoid of medical care centers;

- 2300 m, Yoshida trail - the most popular, because it is easier and full of services (shelters, medical centers...) so ideal for beginners too;

- 2400 m, Fujinomiya trail - the shortest but also the steepest ever, has a medical center and is on average crowded.

All four start from 5ᵃ station (the term "station" indicates the level of difficulty of the climb): from 7ᵃ to 9ᵃ, the last one, the level is maximum. Between ascent and descent the total time is about 10-12 hours. It is therefore necessary to plan, and keep in mind that part of the ascent will be done at night. In fact, if you want to be present at the sunrise show - destination of almost all visitors - the advice is to calculate well the time in order to reach the refuge between 16.00 and 19.00. To rest until midnight, and then continue the climb for about 4 hours arriving at the top right, right for the dawn (at 4.30!).

The official climbing season runs roughly from the beginning of July to the end of August (maximum, until mid-September). Various Shintō ceremonies open the access to Fuji on July 1st and end with a big torchlight procession to the Yoshida sanctuary on August 26th. To venture outside of these dates is possible...but strongly discouraged! Since the climate is always severe and moreover, out of season, the shelters remain closed. In fact, every year, unfortunately, there are deaths, whether from avalanches, slippage, or frostbite... therefore, unless you are superman, don't go there out of season!

photo credits: linkedin.com

No to the "Bullet Climbing"

When climbing Fuji, it is recommended in any case to arrive at 5ᵃ station and stop there for at least a couple of hours, before resuming the ascent, so that your body can adapt to climate and altitude; to always hydrate a lot, in addition to taking several breaks during the climb. It is always not recommended, even more so for beginners, to try everything during the daytime hours to return at sunset. While starting the ascent early in the morning and taking it easy, it can be tiring. This is demonstrated by the upsurge in sickness following which the Japanese government itself was forced to dissuade itself from practicing "crazy climbs" or Bullet Climbing.

By the way: did you know that until the 19th century women could only climb up to the 2ᵃ station? There, they were made to wait for the return of their male relatives, but they went further. This is because at one time she was not considered capable of withstanding the harsh conditions of the mountain and that this would have hindered the practitioners in isolation. Just think that the first woman to climb Fuji in 1833 disguised as a man! Also from the 19th century, then, the first foreigners on the summit.

When and where to best admire it

The best seasons in which to admire it without the clouds constantly interfering, are always autumn and winter - from November to February. Especially winter, in December and January, which are played out depending on the weather and climate. Some years the visibility is better in December, others in January.

The visibility is not optimal instead between April and August, especially in the months of April, June and July, when it is particularly reduced; but also in September, being the latter period of typhoons.

In short, what is decisive in terms of visibility, more than the weather conditions (a sunny day is not equivalent to good visibility!), are the seasons.

Between late summer and early autumn, then occurs the phenomenon of Fuji Rosso so defined because of the color that the mountain assumes at dawn. Since the period in which it occurs is precisely circumscribed, assisting you is considered a good omen. In particular for business and fertility (it seems that the Japanese see in Red Fuji a woman in a state of interest!). In general, that brings good luck and makes one's dreams come true.

photo credits: ameblo.jp/ameba20091/

The best time of the day to observe it in full is always in the morning, especially at 8.00 am. The further you go in the day, the less it is visible for the whole day, the better.

From Tokyo it is visible - mist or clouds permitting - especially from: Metropolitan Government Palace in Shinjuku (on the 45th floor, free entrance!), Roppongi Hills, from the iconic Tokyo Tower, but especially from the impressive SkyTree. You can also do it from the 5th floor of Haneda International Airport, open 24 hours a day! Good to know, in case you are waiting for a flight right at dawn...isn't it?

To keep in mind also the location Miho no Matsubara (三保の松原), historical for the view of Mount Fuji. And, in spring, the spectacle of the "carpet" of Shibazakura, pink moss flowers that cover the meadows at the foot of the mountain. Every year the Shibazakura Festival is celebrated for the occasion (芝桜祭).

You can also get a great view from Mount Takao, 1 hour from Shinjuku, ideal if you have to stay close to Tokyo. Finally, a personal opinion: the view of Fuji rising against the backdrop of the city of Yokohama at sunset is simply wonderful. I could observe it from one of the mini cruises available in the bay.

photo credits: pinterest.it

Japan History: Saitō Hajime

Saitō Hajime (Yamaguchi Hajime, February 18, 1844 – September 28, 1915) was a Japanese samurai of the late Edo period, who served as the captain of the third unit of the Shinsengumi. He was one of the few core members who survived the numerous wars of the Bakumatsu period. He was later known as Fujita Gorō and worked as a police officer in Tokyo during the Meiji Restoration.

Saitō Hajime of the third unit of the Shinsengumi

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: wikipedia.org

He was born in Edo, Musashi Province (now Tokyo) as Yamaguchi Hajime and he had an older brother named Hiroaki and an older sister named Katsu. According to the published records of his family, Saitō left Edo in 1862, after accidentally killing a hatamoto (a samurai in the direct service of the Tokugawa shogunate of feudal Japan).

He went to Kyoto and taught in the dōjō of a man named Yoshida who had relied on Saitō's father Yūsuke in the past. His style of swordsmanship is not clear. According to a tradition of his descendants, his style comes from Ittō-ryū and to be a Mugai Ryū that originates from Yamaguchi Ittō-ryū. He is also considered to have learned Tsuda Ichi-den-ryū and Sekiguchi-ryū.

He adherently lived by the Shinsengumi code "Aku Soku Zan" ( literally: "Slay Evil Immediately", but more poetically rendered as "Swift Death to Evil"), though he never has shown much regard for human life, at some points even letting on that he likes to kill. He was rather arrogant, but none of these flaws prevent him from being a superb investigator and fighter. He expected those involved in the military, whether Shinsengumi swordsmen or Meiji era policemen, to carry out their duties without letting their personal feelings interfere.

He believed in peace and order, even in the society created by his former enemies. Throughout the series, to uphold this new peace, Saitō has often been shown as the foil of Himura Kenshin who walks and carries out his duties in the shadows of society in his own way; following his lifelong code of purpose with devotion, Saitō was the man who did the dirty work, killing off the bad persons. Anyone he considered to be corrupt or despotic was a target for elimination, in the honor of his country and his fallen men.

Even if he was normally serious, Saitō had a slight sense of humor that is also a lot sadistic, shown as he used his sword to casually attempt to stab Sanosuke Sagara in the butt through the roof of the horse carriage they were riding with Himura Kenshin.

During the Kyoto Arc, Saitō joined forces with Himura Kenshin to fight against Shishio Makoto. However, he considered Kenshin to be more of an adversary rather than an ally. Later, after acknowledging Himura Kenshin’s vow to never kill again, Saitō decided to put an end to their rivalry.

Saitō was an able observer and a quick analyst (working as a spy for the Meiji government). In addition to being a skilled swordsman, he is revealed to possess immense physical strength when he punched the herculean Sagara Sanosuke in a hand-to-hand fistfight. He considered Sanosuke to be a dimwitted amateur with mild potential, due mostly to Sano's lack of insight.

Saitō was highly recognizable by his narrow eyes, "spider-like" strands of hair in front of his forehead (he was also said to resemble a wolf), his propensity for smoking and the katana on his left side.

Shinsengumi Period

As a member of the Shinsengumi, Saitō was said to be an introvert and a mysterious person; a common description of his personality says he " he was not a man predisposed to small talk" but unusually tall 180 cm. He was also noted to be very dignified, especially in his later years, he always made sure that his obi was tied properly and when he walked he was careful not to drag his feet and he always sat in the formal position, called seiza. He also was very alert so that he could react instantly to any situations that might occur.

He was known to be very intimidating when he wanted to be. Along with his duties as Captain of the Third Squad in the Shinsengumi, he was also responsible for weeding out any potential spies within the Shinsengumi ranks.

His original position within the Shinsengumi was assistant vice commander. During the Ikedaya incident on July 8, 1864, Saitō was with Hijikata Toshizō's group that arrived later at the Ikedaya Inn.

In August 20, 1864, Saitō and the rest of the Shinsengumi took part in the Kinmon incident against the Chōshū rebels. In the reorganization of the ranks in November 1864, he was first assigned as the fourth unit's captain and would later receive an award from the shogunate for his part in the Kinmon incident.

At the Shinsengumi new headquarters at Nishi Hongan-ji in April 1865, he was assigned as the third unit's captain. Saitō was considered to be on the same level of swordsmanship as the first troop captain Okita Sōji and the second troop captain Nagakura Shinpachi. In fact, it seems that Okita feared his sword skill.

Despite prior connections to Aizu, his descendants dispute that he served as a spy. His controversial reputation comes from accounts that he executed several corrupt members of the Shinsengumi; however, rumors vary as to his role in the deaths of Tani Sanjūrō in 1866 and Takeda Kanryūsai in 1867. His role as an internal spy for the Shinsengumi is also questionable; he is said to have been instructed to join Itō Kashitarō's splinter group Goryō Eji Kōdai-ji faction, to spy on them, which eventually led to the Aburanokōji incident in December 13, 1867.

Together with the rest of the Shinsengumi, he became a hatamoto in 1867. In late December 1867, Saitō and a group of six members of the Shinsengumi were charged with protecting Miura Kyūtarō, who was one of the main suspects in the murder of Sakamoto Ryōma. On January 1, 1868, they fought against sixteen assassins who tried to kill Miura in revenge at the Tenmaya Inn for what was known as the Tenmaya incident.

After the outbreak of the Boshin war from January 27, 1868 onwards, Saitō, under the name of Yamaguchi Jirō, participated in the Shinsengumi's fight during the battle of Toba-Fushimi and the battle of Kōshū-Katsunuma, before retiring with the surviving members in Edo and later in the domain of Aizu.

Saitō became commander of the Aizu Shinsengumi around May 26, 1868 and continued in the battle of Shirakawa. After the battle of Bonari Pass, when Hijikata decided to withdraw from Aizu, Saitō and a small group of 20 members separated from Hijikata and the rest of the surviving Shinsengumi, continued to fight alongside the Aizu army against the imperial army until the end of the battle of Aizu. This separation was recorded in the diary of the conservative Kuwana Taniguchi Shirōbei, where it was recorded as an event that also involved Ōtori Keisuke, who Hijikata asked to take command of the Shinsengumi; therefore the aforementioned clash was not with Hijikata.

Saitō, together with the few remaining men of the Shinsengumi who went with him, fought against the imperial army at Nyorai-dō), where they were severely outnumbered. It was during the battle of Nyorai-dō that Saitō was thought to have been killed in action; however, he managed to return to the lines of Aizu and joined the army of Aizu's domain as a member of the Suzakutai. After the fall of the Aizuwakamatsu castle, Saitō and the five surviving members joined a group of former Aizu services who traveled southwest to the Takada domain in Echigo province, where they were held as prisoners of war. In the registers listing the Aizu men detained in Takada, Saitō is registered as Ichinose Denpachi.

Meiji Restoration

Saitō, under the new name of Fujita Gorō, went to Tonami, the new domain of the Matsudaira clan of Aizu. He settled with Kurasawa Heijiemon, the karō of Aizu who was an old friend of his from Kyoto. Kurasawa was involved in the migration of Aizu samurai to Tonami and the construction of settlements in Tonami, particularly in the village of Gonohe. In Tonami, Fujita met Shinoda Yaso, daughter of an Aizu believer. The two met through Kurasawa, who then lived with Ueda Shichirō. Kurasawa sponsored the marriage of Fujita and Yaso on August 25, 1871. It was also during this period that Fujita may have been associated with the Police Office. Fujita and Yaso moved out of the Kurasawa house on February 10. When he left Tonami for Tokyo on June 10, 1874, Yaso moved to Tokyo with Kurasawa and the last registration of the Kurasawa family dates back to 1876. It is not known what happened after that. It was during this period that Fujita Gorō started working as a police officer in the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department.

In 1874 Fujita married Takagi Tokio, the daughter of Takagi Kojūrō, a servant of the Aizu domain. Her original name was Sada; she served for a time as a companion of Matsudaira Teru. Fujita and Tokio had three children: Tsutomu (1876-1956); Tsuyoshi (1879-1946); and Tatsuo (1886-1945). Tsutomu and his wife Nishino Midori had seven children; the Fujita family continues to this day through Tarō and Naoko Fujita, the children of Tsutomu's second son, Makoto. Fujita's third son, Tatsuo, was adopted by the Numazawa family, maternal relatives of Tokyo whose family had been almost annihilated during the Boshin war.

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Fujita fought on the Meiji government's side during Saigō Takamori's Satsuma rebellion, as a member of the police forces sent to support the Imperial Japanese Army.

During his lifetime, Fujita Gorō shared some of his Shinsengumi experiences with a select few, but he didn’t write anything about his activity in the Shinsengumi as Nagakura Shinpachi did. During his life in the Meiji period, Fujita was the only one who was authorized by the government to carry a katana despite the collapse of the Tokugawa rule. In 1875, Fujita assisted Nagakura Shinpachi (as Sugimura Yoshie) and Matsumoto Ryōjun in setting up a memorial monument known as Grave of Shinsengumi in honor of Kondō Isami, Hijikata Toshizō, and other deceased Shinsengumi members at Itabashi, Tokyo.

Following his retirement from Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department in 1890, Fujita worked as a guard for Tokyo National Museum, and later as a clerk and accountant for Tokyo Women's Normal School from 1899.

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Fujita's heavy drinking was believed to have contributed to his death from a stomach ulcer. He died in 1915 at age 72, sitting in seiza in his living room. Upon his will, he was buried at Amidaji, Aizuwakamatsu, Fukushima, Japan.