Sakè: tre curiosità sulla bevanda simbolo del Giappone

Il sake non è semplicemente un alcolico: è un autentico pezzo di cultura giapponese, strettamente legato alla storia, alle tradizioni e persino alla spiritualità del Paese del Sol Levante. Sebbene venga spesso definito "vino di riso", la sua produzione è tutta speciale e il suo significato va ben oltre il semplice gusto. Per parlare delle bevande a base di riso, l'ideogramma sake [酒] si riferisce in generale all'alcool, ma viene pronunciato shu. Quando i giapponesi parlano di bevande realizzate con il riso, usano il termine nihonshu [日本酒], che significa "bevanda del Giappone".

E ora, preparatevi a scoprire tre curiosità affascinanti che vi faranno vedere il sake sotto una luce completamente nuova!

1. Il sake non è un distillato

Molti credono che il sake sia simile ai liquori o ai distillati, ma in realtà il suo processo di produzione è più vicino a quello della birra. Il riso utilizzato viene prima levigato per eliminare le impurità, poi cotto a vapore e fatto fermentare grazie a un fungo speciale chiamato koji. Questo trasforma gli amidi in zuccheri, permettendo al lievito di avviare la fermentazione alcolica.

Il risultato? Una bevanda dal gusto complesso e delicato, con una gradazione alcolica che si aggira tra il 13% e il 16%. E se pensavate che esistesse solo un tipo di sakè, ripensateci: ne esistono varianti più leggere, non filtrate, frizzanti e persino invecchiate!

2. Un legame con il sacro

Il sake non è solo un piacere per il palato, ma anche un elemento profondamente radicato nelle tradizioni religiose giapponesi. Antiche leggende narrano che persino gli dèi lo apprezzavano: si dice che il dio delle tempeste Susanoo-no-Mikoto abbia sconfitto un drago offrendogli otto barili di sake.

Ancora oggi, questa bevanda viene usata nei rituali shintoisti, specialmente nei matrimoni e nelle offerte ai kami (le divinità giapponesi). Durante alcuni festival, come il Doburoku Matsuri, viene distribuito un sakè non filtrato ai partecipanti, creando un legame tra il sacro e la convivialità.

3. Il galateo del sake

Non basta riempire un bicchiere e bere, il sake ha un vero e proprio codice di comportamento. Tradizionalmente si beve in piccole tazzine di ceramica (choko) o in eleganti scatoline di legno (masu). Ma la regola d’oro è una: mai versarselo da soli! È un gesto poco educato, mentre versarlo agli altri è un segno di rispetto e condivisione.

Anche la temperatura conta: d’inverno si può gustare caldo, mentre nei mesi estivi è più apprezzato fresco o persino freddo. Ogni metodo di servizio esalta aromi diversi, rendendo ogni sorso un’esperienza unica.

Un brindisi alla tradizione!

Il sake non è solo una bevanda, è un viaggio nella cultura giapponese. La prossima volta che avrete l’occasione di assaggiarlo, ricordatevi di alzare la tazzina e brindare con un tradizionale "Kanpai!" – e magari stupire i vostri amici con queste curiosità!

Il nostro rapporto con il Sake

Japan Italy Bridge si è spesso dedicata alla promozione del sake, portando avanti numerose iniziative, tra cui la Bunka Academy. L’obiettivo è stato quello di far conoscere anche in Italia la consapevolezza di come apprezzare il sake, sottolineando che non si tratta di una grappa, ma di un vero e proprio vino. Non è una bevanda da consumare solo a fine pasto, ma da gustare durante tutta la cena. A differenza del vino, il sake non copre i sapori dei piatti, ma li esalta. Per questo motivo, Japan Italy Bridge ha organizzato eventi in collaborazione con esperti giapponesi, che hanno condiviso con il pubblico la storia, il processo di produzione e i segreti del consumo e della conservazione del sake.

Se siete curiosi, vi invitiamo a dare un’occhiata al nostro portfolio e scoprire tutte le collaborazioni che abbiamo portato avanti.

Alla scoperta delle tre grandi varianti di soba in Giappone

La soba, i tradizionali noodles di grano saraceno, è uno dei piatti più iconici della cucina giapponese. Pur essendo diffusa in tutto il Paese, ogni regione ha sviluppato la propria variante, con caratteristiche uniche che la rendono speciale. Ecco tre delle versioni più famose che vale la pena assaggiare durante un viaggio in Giappone!

1. Togakushi Soba – La delicatezza montana di Nagano

Nel cuore delle Alpi giapponesi, la regione di Nagano è rinomata per la qualità della sua soba, in particolare quella di Togakushi. Questa versione si distingue per la lavorazione artigianale e la presentazione: i noodles vengono serviti freddi su un vassoio di bambù chiamato “zaru”, accompagnati da una salsa a base di soia (tsuyu) e spesso arricchiti con daikon grattugiato e wasabi. La purezza dell’acqua di montagna utilizzata nella preparazione contribuisce a donare un sapore fresco e raffinato.

2. Izumo Soba – Il gusto intenso del Giappone occidentale

Originaria della prefettura di Shimane, l’Izumo soba ha una consistenza più robusta e un sapore deciso grazie all’uso della farina di grano saraceno intero, che conserva il colore scuro e l’aroma naturale del cereale. Un tratto distintivo di questa varietà è la sua modalità di servizio: spesso presentata nel “warigo”, tre piccoli contenitori impilati, nei quali si versa direttamente la salsa e i condimenti, creando un mix di sapori ad ogni boccone.

3. Wanko Soba – Un’esperienza gastronomica unica a Iwate

Più che un semplice piatto, il Wanko soba è una vera e propria sfida culinaria. Tipica della prefettura di Iwate, questa specialità prevede il servizio di piccole porzioni di soba in ciotole individuali, che vengono continuamente riempite dal personale finché il commensale non si arrende. È un’esperienza divertente e interattiva, perfetta per chi vuole mettersi alla prova mentre assapora il gusto autentico di questa varietà regionale.

Se siete amanti della cucina giapponese, provare queste tre versioni di soba è un’occasione imperdibile per scoprire la diversità gastronomica del Paese. Ogni regione offre non solo un sapore unico, ma anche un’esperienza culturale che arricchisce ogni viaggio! Potete approfittare delle nostre proposte e offerte cliccando QUI: Your Japan vi farà venire l’acquolina in bocca!

Japan History: Furuta Shigenari

Furuta Shigenari (Distretto di Motosu, prefettura di Gifu, 1544 – July 6, 1615) era un guerriero giapponese vissuto durante il periodo Sengoku. Figlio del maestro di cerimonia del tè Furuta Shigesada (conosciuto con il suo nome buddista Kannami, in seguito ribattezzato Shuzen Shigemasa) che era anche uno dei fratelli minori del signore del castello di Yamaguchi-jo nella contea di Motosu-gun, provincia di Mino. Perseguendo la carriera di guerriero, Oribe acquisì anche un gusto sofisticato per la cerimonia del tè grazie a suo padre e sembra che sia stato adottato da suo zio.

Furuta Shigenari, il samurai che era anche maestro di cerimonia del tè

Autore: SaiKaiAngel

photo credit: https://it.wikipedia.org/

Furuta Shigenari divenne il servitore di Oda Nobunaga quando Nobunaga attaccò la provincia di Mino nel 1567. Nel 1569, Shigenari sposò Sen, una delle sorelle minori di Nakagawa Kiyohide (il signore del castello di Ibaraki-jo nella provincia di Settsu).

Nel 1576, Oribe divenne un amministratore di Kamikuze no sho (ora, Minami-ku Ward di Kyoto City), distretto di Otokuni-gun, provincia di Yamashiro. Successivamente si unì all'esercito di Hashiba Hideyoshi (poi Toyotomi Hideyoshi) durante l'attacco alla provincia di Harima e all'esercito di Akechi Mitsuhide durante l'attacco alla provincia di Tanba, facendo una carriera di successo come leader di guerra nonostante il suo piccolo stipendio di 300 koku.

Come maestro della cerimonia del tè, è ampiamente conosciuto come Furuta Oribe. Il suo nome comune era Sasuke, il suo primo nome era Keian. Il nome 'Oribe' come maestro della cerimonia del tè ha avuto origine dal fatto che è stato premiato con il grado di Junior Fifth Rank, Lower Grade, Director of Weaving Office.

Nel periodo di unione con Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Furuta Shigenari conobbe il maestro Rikyū diventando uno dei suoi allievi preferiti per circa dieci anni durante i quali scrisse due opere: Oribe Densho ("Il libro dei segreti") e Oribe Hyakka ("I cento precetti"). Il suo rapporto con Rikyū fu così intenso da non aver paura di fare disobbedienza al comune signore Hideyoshi nel momento in cui Rikyū partì in esilio per Sakai. Durante il dominio di Toyotomi Hideyoshi, la generazione di maestri del tè del periodo di Nobunaga, Yamanoue Sōji, Sen no Rikyū, Tsuda Sogyu, Imai Sokyu, si estinse in pochi anni. Tutti i maestri del tè erano oppositori filosofici e politici dell'espansionismo militare di signori della guerra come Hideyoshi, e l'importanza della disciplina del tè li poneva in grande autorevolezza sociale e politica, quindi, come Rikyu, furono esiliati o costretti al suicidio. L'arte del tè, conclusa la generazione di Nobunaga divenne cerimonia di Stato del periodo della Restaurazione Tokugawa e Furuta Shigenari divenne il più importante maestro del tè della nuova generazione. Insegnò anche allo shōgun Tokugawa Hidetada, Kobori Enshū e Honami Kōetsu. Accusato tuttavia di ordire una cospirazione ai danni dei Tokugawa gli fu ordinato il seppuku nel 1615.

La sua influenza

L'influenza di Furuta Oribe comprendeva tutta la pratica cerimoniale dalla prassi della preparazione del tè, agli stili artistici e architettonici, all'arredamento e allo stile delle ceramiche.

Infatti Oribe-ryū era lo stile di cerimonia curato da lui, come lo stile delle ceramiche Oribe-yaki. Disegnò anche un tipo di lanterna (tōrō) per il giardino del tè, conosciuta come Oribe-dōrō.

Arriva la Kimono Experience a TENOHA Milano

Arriva la KIMONO EXPERIENCE con Giappone in Italia, Milano Kimono e TENOHA Milano!

L’Associazione Giappone In Italia ha creato un “experience” più unica in collaborazione con Milano Kimono e TENOHA Milano, stiamo parlando della KIMONO EXPERIENCE!

Prova il vero Giappone con la Kimono Experience

Autore: SaiKaiAngel

Avete voglia di trascorrere momenti fuori dal tempo e unici? In questo momento in cui tutto è frenetico, perchè non prendersi un momento per noi stessi? Senza impegni, stress o confusione? Immergiamoci nell’amore per il Giappone e facciamolo nel migliore dei modi! Vi siete mai chiesti “Ma io come starei in Yukata o in kimono?” Io penso di sì, almeno, io me lo sono chiesta molte volte e finalmente sono riuscita a vedermi con il vestito tradizionale giapponese! Come ben sapete, l’Associazione Giappone In Italia, TENOHA Milano e noi di Japan Italy Bridge lavoriamo con un focus comune: costruire un ponte tra Giappone e Italia promuovendo la cultura giapponese qui a casa nostra.

Un’esperienza assolutamente speciale che vi permetterà di sentirvi in Giappone. Se non si può prendere l’aereo, come si fa a vivere il Giappone? Potete farlo come sempre nell’angolo di Giappone qui in Italia, TENOHA Milano! Non solo, dal 15 al 30 Giugno, potrete godere della “KIMONO EXPERIENCE”! Di cosa si tratta esattamente?

Di cosa si tratta?

KIMONO EXPERIENCE è una mostra allestita negli spazi di TENOHA Milano dal 15 al 30 giugno, con i kimono più belli e le foto di Alberto Moro, Presidente di Giappone in Italia e autore del libro “il Mio Giappone”. Troverete le foto di chi ha voluto indossare il kimono per le vie di Milano anche senza essere giapponese! Questo è l’obiettivo di KIMONO EXPERIENCE, far vivere a chi non è giapponese l’emozione del Sol Levante, non solo intorno, ma anche addosso. Sì, perchè, prenotandosi, si potrà avere la gioia di indossare uno Yukata e di essere fotografati niente meno che dal Presidente di Giappone In Italia, Alberto Moro che come ben sapete è anche un famosissimo fotografo.

Immaginatevi nell’atmosfera giapponese, avvolti in uno Yukata (la versione estiva del kimono) che la maestra di vestizione Yurie Sugiyama vi farà indossare, fotografati da Alberto Moro nell’incredibile e giapponese TENOHA Milano. Un sogno? No! Una realtà che vi sta aspettando!

Potrete visitare la mostra dal 15 al 30 giugno, dalle 10 alle 20, nello spazio Pop-up di TENOHA Milano, in Via Vigevano 18.

Se invece desiderate vestirvi e avere la vostra foto in Yukata, ricordate che la maestra di vestizione Yurie Sugiyama sarà disponibile dal 17 al 20 e dal 24 al 27 giugno, dalle 10.30 alle 13 e dalle 15 alle 18.00. Nonostante la vestizione sarà gratuita, nel form da compilare che trovate qui di seguito, vi verrà richiesta una caparra di prenotazione che sarà restituita nel momento in cui vi presentate alla KIMONO EXPERIENCE !

Non solo! Se desiderate, potrete acquistare la vostra foto in kimono come ricordo unico ed irripetibile della giornata. Vi chiederanno sicuramente quando siete volati in Giappone, perchè sono momenti che difficilmente possono ripetersi qui in Italia.

KIMONO EXPERIENCE, un’esperienza da non perdere, per portare nuovamente il Giappone In Italia, come recita il nome dell’Associazione che l’ha creata.

Ovviamente noi di Japan Italy Bridge vi aspettiamo numerosi!

>> PRENOTA ORA LA TUA KIMONO EXPERIENCE! <<

Fino ad esaurimento posti.

photo credits: Alberto Moro, Presidente Associazione Giappone in Italia

Japan History: Fukushima Masanori

Fukushima Masanori (1561 – Agosto 26, 1624) , il cui nome inizialmente fu Ichimatsu, nacque nella provincia di Owari.

Fukushima Masanori, una delle Sette lance di Shizugatake

Autore: SaiKaiAngel

photo credit: wikipedia.org

Figlio di Fukushima Masanobu, Fukushima Masanori è stato un generale giapponese e un daimyō al servizio dei Tokugawa, famoso anche per essere una delle Sette lance di Shizugatake.

Si dice anche che potesse essere stato cugino di Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Masanori assaltò il castello di Miki nella provincia di Harima e, durante la battaglia di Shizugatake nel 1583, sconfisse Haigo Gozaemon ed ebbe l'onore di prendere la prima testa, quella del generale nemico Ogasato Ieyoshi.

Fukushima Masanori prese parte a molte delle campagne di Hideyoshi; fu dopo la campagna di Kyūshū (1586-1587) che divenne daimyō ricevendo il feudo di Imabari nella provincia di Iyo; poco dopo prese parte alle invasioni giapponesi della Corea (1592-1598) e si distinse ancora una volta durante la battaglia di Chungju.

In seguito al suo coinvolgimento nella campagna coreana, Masanori partecipò alla ricerca di Toyotomi Hidetsugu. Condusse 10.000 uomini nel 1595, circondò il tempio di Seiganji sul monte Kōya e attese che Hidetsugu si suicidasse. Alla morte di Hidetsugu, Masanori ricevette l'ex feudo di Hidetsugu di Kiyosu nella provincia di Owari.

Essendo ostile a Ishida Mitsunari, Fukushima Masanori entrò in simpatia di Tokugawa Ieyasu; Ishida con un pretesto bruciò il castello di Masanori e durante la battaglia di Sekigahara sferrò il primo attacco alle truppe di Ukita rimanendo in prima linea per tutto il tempo. Vinta la battaglia e catturato Ishida, Masanori decapitò il daimyō nemico a Kyoto insieme ad Anko e Konishi. Masanori ricevette il feudo di Hiroshima ad Aki, ma Ieyasu non si fidò mai completamente di Masanori, per questo gli ordinò di ricostruire il castello di Nagoya per fargli spendere parte del suo reddito.

A quel punto, Masanori chiese di partecipare all'assedio di Osaka (1614-15), ma gli fu costretto a rimanere a Edo. Il nuovo Shōgun, Hidetada, si fidava ancor meno di Masanori e, dopo la morte di Ieyasu, lo accusò di malgoverno e lo trasferì al feudo di Kawanakajima. Il fratello minore di Fukushima Masanori, Masayori, aveva già perso il suo feudo a Yamato nel 1615.

Il posto di comando di Fukushima Masanori a Sekigahara

photo credit: samurai-world.com

Sembra che i suoi discendenti divennero hatamoto al servizio dello shogunato Tokugawa. Gli hatamoto erano samurai sotto il diretto controllo dello Shogunato di Tokugawa nel Giappone feudale. Tutti e tre gli shogunati della storia del Giappone avevano dei referenti diretti, soltanto che in quelli precedenti tali personaggi prendevano il nome di gokenin. Comunque, nel periodo Edo, gli hatamoto erano i vassalli di grado più elevato della dinastia Tokugawa e i gokenin erano i vassalli minori.

Fukushima Masanori possedeva una delle tre grandi lance del Giappone: Nihongo, oppure anche chiamata Nippongo (日本号). Usata nel Palazzo Imperiale, Masanori Fukushima possedette la Nihongo, per poi farla passare in mano a Tahei Mori. È stata recuperata, restaurata ed ora si trova al The Fukuoka City Museum.

Japan History: Chōsokabe Motochika

Chōsokabe Motochika (1538 – 11 luglio 1599) è stato un daimyō giapponese del periodo Sengoku e nacque nel castello di Okō del distretto Nagaoka nella provincia di Tosa. Figlio maggiore di Chōsokabe Kunichika, Chōsokabe Motochika era un ragazzo così dolce da preoccupare suo padre per questa sua natura, sembra infatti fosse stato soprannominato Himewako, "Piccola principessa", dai vassalli.

Chōsokabe Motochika, soprannominato Himewako

Autore: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Nonostante queste preoccupazioni, Chōsokabe Motochika si dimostrò invece un abile e coraggioso guerriero durante la sua prima battaglia sconfiggendo il clan Motoyama nel 1560, durante la battaglia di Tonomoto. Dopo la sconfitta dei Motoyama e formando alleanze con le famiglie locali, Chōsokabe Motochika fu in grado di costruire la sua base di potere sulla pianura di Kōchi. Pur rimanendo fedele agli Ichijō, Motochika con la forza di 7000 uomini marciò sul clan Aki, rivali dei Chōsokabe, sconfiggendoli nel 1569 durante la battaglia di Yanagare. A quel punto Chōsokabe Motochika poté concentrarsi sugli Ichijō.

Durante il governo del quartiere Hata di Tosa, Ichijō Kanesada era un leader molto impopolare e grazie a questo, Motochika non perse tempo a marciare sul quartier generale degli Ichijō a Nakamura e nel 1573 Kanesada fuggì. A quel punto, Il clan Ōtomo fornì a Kanesada una flotta e con quella tornò guidando una spedizione che i Chōsokabe sconfissero nella battaglia di Shimantogawa. A questo punto Kanesada si sottomise ai Chōsokabe che probabilmente lo fecero assassinare nel 1585.

Chōsokabe Motochika divenne unico sovrano di Tosa e uno dei problemi che i Chōsokabe dovettero affrontare fu proprio il territorio che possedevano. A causa della sua povertà, non riusciva a pagare i suoi generali, per questo cominciò a guardare le province vicine.

L'unificazione di Shikoku

Dopo la conquista di Tosa, Chōsokabe Motochika si preparò per un'invasione della provincia di Iyo, contro il signore di quella provincia Kōno Michinao, un daimyō che era stato cacciato dal suo dominio dal clan Utsunomiya, aiutato solo dal clan Mōri. Ma in quel momento, il clan Mōri era in guerra contro Oda Nobunaga, per questo non riuscì a dare aiuto a Michinao, comunque la campagna nella provincia di Iyo non fu semplice. Nel 1579 un esercito Chōsokabe di 7000 uomini, guidato da Hisatake Chikanobu, attaccò il castello di Okamoto, detenuto da Doi Kiyoyoshi al sud di Iyo.

Durante questo assedio, Chikanobu fu ucciso e il suo esercito sconfitto. Motochika ritornò l’ano seguente con circa 30.000 uomini a Iyo e costrinse Michinao a fuggire nella provincia di Bungo. Grazie al fatto che i Mōri e gli Ōtomo erano impegnati su altri fronti, Motochika fu libero di proseguire la sua conquista dell'isola e nel 1582 fu in grado di proseguire con le incursioni sulla provincia di Awa per sconfiggere il clan Sogo, per consegire nel 1583 il controllo dell’isola.

photo credits: mvbennett.wordpress.com

Nel 1579 Chōsokabe Motochika entrò in comunicazione con Nobunaga che sembrava averlo lodato, nonostante in privato si riferiva a lui come un pipistrello su un'isola senza uccelli e aveva pianificato di conquistare Shikoku in futuro, progettando per darla al figlio Nobutaka. Questo non avvenne, a causa della morte di Nobunaga nel 1582.

Coinvolto nella successiva disputa tra Toyotomi Hideyoshi e Tokugawa Ieyasu l'anno successivo, promise a Tokugawa il suo supporto, sebbene non fece mosse dirette a tal fine. Hideyoshi invece mandò Sengoku Hidehisa a bloccare qualsiasi interferenza da parte di Motochika. La campagna di Komaki tra Hideyoshi e Ieyasu si concluse con un trattato di pace e nel 1584 Hideyoshi invase Shikoku, con 30.000 truppe del clan Môri e altre 60.000 di Hashiba Hidenaga. Motochika riuscì a mantenere il controllo della provincia di Tosa grazie ai termini decisi da Hideyoshi

Chōsokabe Motochika viene ricordato sia per il suo Codice di 100 articoli dei Chōsokabe e per la sua tenacia nel fondare una città-castello molto forte da Oko a Otazaka e poi a Urado. Tuttavia i problemi causati dalla nomina di Morichika come erede provocò la disfatta del clan.

Dopo la morte di Nobuchika in battaglia, Hideyoshi suggerì che il secondo figlio di Motochika, Chikakazu, fosse nominato erede. Ma quando Motochika si dimise rese suo erede Morichika, il suo quarto figlio, perchè riteneva Chikakazu non fisicamente in grado di assumere il comando della famiglia. Con questo pensiero, Chikakazu si ritirò e morì di malattia nel 1587. Quando Chōsokabe Motochika fu chiamato per l'invasione di Kyūshū da parte di Hideyoshi, insieme a Sengoku Hidehisa. La loro missione fu quella di sollevare l'assedio del clan Ōtomi.

Nonostante i saggi consigli di Chōsokabe Motochika, i generali Ōtomo e Sengoku non adottarono una posizione difensiva e attaccarono le forze del clan Shimazu nella battaglia di Hetsugigawa sconfiggendo le truppe alleate, ma nello stesso momento morì Nobuchika, l’erede di Motochika. A quel punto Toyotomi Hideyoshi elogiò il pensiero di Motochika e gli offrì Ōsumi come compensazione per la sua perdita, che però fu rifiutata.

Nel 1590 Motochika guidò un contingente navale nell'assedio di Odawara e nel 1592 comandò 3000 soldati nell'invasione della Corea. Al suo ritorno dalla Corea si ritirò a Fushimi, divenne monaco e morì l'11 luglio 1599.

Sakura, approfondimento sul fiore simbolo del Giappone

Continua l'appuntamento con gli approfondimenti sulla cultura giapponese e oggi parliamo di Sakura, il fiore simbolo del Sol Levante. “Il fiore perfetto è una cosa rara. Si potrebbe trascorrere la vita a cercarne uno, e non sarebbe una vita sprecata.”

Sakura 桜 Fiore simbolo del Giappone

Autore Ospite: Flavia

Così, esordiva Ken Watanabe in una scena del celebre film ‘L’Ultimo Samurai’ (2003) nei panni del samurai ribelle Katsumoto, sulla cornice di un bellissimo giardino giapponese. Come non ricordare questa scena del film che, aldilà di alcune inesattezze storiche, è in grado di regalarci momenti come questo. Circondato da splendidi alberi in fiore, Katsumoto-Watanabe altro non fa che mettere in scena il prototipo della sensibilità estetica giapponese verso la natura. In questo caso, verso i fiori. Ma qui è di un fiore in particolare che stiamo parlando…quello di ciliegio, indiscusso oggetto di secolare ammirazione: il Sakura ( 桜 · さくら ).

Conosciamo tutti i fiori ciliegio: la loro bellezza è evidente, l’ammirarli una conseguenza naturale. Questo direi che non necessita di spiegazioni. Possiamo però parlare della particolare importanza che questo delicato fiorellino riveste in Giappone, tanto da divenirne simbolo “morale” (quello ufficiale è il crisantemo).

Il termine “Sakura” si riferisce sia al fiore sia all’albero – noto come “ciliegio giapponese” –, un tipo di ciliegio caratteristico dell’estremo oriente. Le varietà di Sakura che costellano il territorio giapponese, metropoli comprese, sono circa un centinaio. Ma le più diffuse sono lo Yamazakura e soprattutto il (Somei-)Yoshino, dal tipico colore rosa pallido-bianco, contemplato dai giapponesi da ormai centinaia di primavere.

photo credits: japan.stripes.com

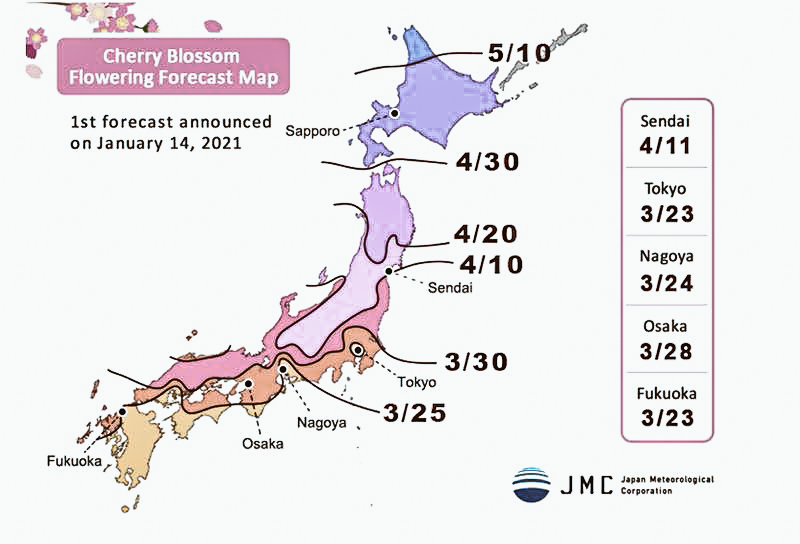

Portatore di una simbologia particolare, evocativo di profondi significati, il Sakura è una vera e propria istituzione in Giappone. Compare nella celebre monetina da 100 Yen e fa da cornice al Fuji san, l’altro grande simbolo del Giappone, sul retro dell’attuale banconota da 1000 Yen. È così amato che l’Agenzia Meteorologica Nazionale ogni anno emana lo speciale bollettino Sakura Zensen ( 桜前線 ) per aggiornare sullo stato della fioritura. I media giornalmente informano la popolazione sugli spot migliori, che può così regolarsi per l’amata attività dell’Hanami (lett. l’osservare i fiori), decidendo dove e che varietà di Sakura ammirare.

La fioritura procede da sud a nord, dato che il clima è più mite nelle zone meridionali. Quindi, se arrivate in Giappone che nel centro-sud la fioritura è già passata, guardate il calendario: potreste ancora essere in tempo per beccarli ad Hokkaidō!

Mankai 🌸 La fioritura

Il tempo medio della fioritura varia con la collocazione geografica ma in ogni caso è breve: pochi giorni, massimo una decina giorni. Parte da Okinawa, intorno a fine gennaio, procedendo man mano verso nord con gli ultimi boccioli che si aprono verso metà maggio a Hokkaidō. Questo, il periodo di tempo indicativo. Maltempo, perturbazioni o cambi di temperatura improvvisi possono ovviamente incidere sulla durata della fioritura, considerata poi l’estrema delicatezza del fiorellino. Tutto dipende dal clima e dall’anno: può capitare che i fiori sboccino un po’ prima, o un po’ dopo; oppure che lo sbocciare sia interrotto da un brusco cambio climatico. Il momento del boom della fioritura è noto come Mankai (満開) che infatti significa “piena apertura”.

photo credits: japan.stripes.com

Come anticipato, gran parte dei ciliegi sono della varietà Somei-Yoshino, ma si contano oltre cento specie. Alcune anche in grado di produrre frutti commestibili. Dei criteri per distinguerne tra i diversi tipi, il più immediato è senz’altro quello del numero di petali, che possono arrivare a dieci, venti o anche di più. Quelli più diffusi rimangono i classici Sakura a cinque petali, sia fra quelli selvatici sia fra quelli coltivati.

🌸 Tipi di Sakura

Ma vediamo alcuni esempi di ciliegi più particolari. Oltre al Somei-Yoshino, il più coltivato e che va per la maggiore, possiamo trovare:

- Yama-zakura (山桜), ossia il “Ciliegio di montagna”. Molto amato, si colloca subito dopo al Somei-Yoshino in termini di popolarità. Presenta grandi boccioli rosa e ha cinque petali.

- Fuyu-zakura (冬桜), ovvero “Sakura invernale”. Come suggerisce il nome, è un ciliegio che comincia a sbocciare in autunno per proseguire in inverno, sebbene non in modo continuativo.

- Yae-zakura (八重桜), il “Ciliegio doppio”. Chiamato così per via del bocciolo “rinforzato”, ossia molto corposo, con più di cinque petali. È associato all’antica capitale Nara (奈良).

- Shidare-zakura (枝垂桜), cioè “Ciliegio piangente” poiché i suoi rami cascano, come fosse un salice, creando una cascata di fiori rosa. È fiore ufficiale della prefettura di Kyōto.

- Ichiyō (一葉), “una foglia”. Deve il suo nome a un pistillo, simile a una foglia, che fuoriesce dal suo centro quando completamente aperto. È uno di quelli che può avere da 20 a 40 petali.

photo credits: Akemi K on Flickr, medigaku.com, Pinterest

Si definiscono poi Ippon-zakura (一本桜), tutti gli alberi di ciliegio “in solitaria”, ovvero piantati singolarmente. Tra questi, come non ricordare i tre grandi ciliegi del Giappone, i Sandai-zakura (三大桜). Il trio è composto dal Jindai-zakura a Yamanashi, dall’Usuzumi-zakura a Gifu e dal Takizakura a Fukushima. Jindai e Usuzumi appartengono alla varietà Edohigan (da cui deriva anche il Yoshino), mentre il Takizakura è un esemplare di ciliegio piangente. In particolare il Jindai-zakura, situato nel tempio Jissōji (實相寺), è forse il più antico in Giappone: ha circa duemila anni e una circonferenza di 13 metri e mezzo!

Primavera (春), stagione della speranza

L’atto di contemplare gli alberi in fiore risalirebbe al periodo Nara (VIII sec.). Dapprima appannaggio della sola corte imperiale di Kyōto, nei secoli si è estesa alla categoria dei samurai prima e al resto della popolazione poi. Diciamo che in principio fu il pruno (梅·Ume), a esser oggetto d’attenzione. Il pruno rappresentava il legame con la Cina, essendone originario. Ma già dal periodo Heian (VIII-XII sec.), complice l’interruzione dei rapporti con la Terra di Mezzo, l’Ume venne spodestato dal più autoctono Sakura. Da allora, le poesie a tema primavera iniziarono a riferirsi ai Sakura anche solo con il termine “fiori” (花·Hana) e la parola “Hanami” divenne anch’essa intercambiabile con “sakura”. Dettagli linguistici, tuttavia, indicativi.

La primavera (春· Haru) si caratterizza da sempre come un simbolo di rinascita, di potenza generatrice.

Anticamente la fioritura dei ciliegi era associata alla prosperità, poiché presagiva l’abbondanza della raccolta del riso. Per propiziarsi un buon raccolto l'anno successivo, l'inizio della stagione di semina era aperto da una serie di rituali che si chiudevano con allegre celebrazioni sotto i Sakura. Nel XVIII poi, lo shōgun Yoshimune Tokugawa promosse ulteriormente questa usanza disponendo la piantagione di alberi di Sakura in diverse aree.

Oggi, la primavera è la stagione di studenti, diplomati e laureati, che confidano nel buon auspicio rappresentato dalla fioritura. Nel mese di aprile infatti, per gli studenti si apre il nuovo anno scolastico, mentre laureati e molti diplomati si apprestano ad entrare nel mondo del lavoro. Aprile segna anche l’inizio del nuovo anno fiscale in Giappone. Insomma, la stagione dei ciliegi porta con sé un po’ di inizi in quella terra. Pertanto, la si celebra a dovere con il Sakura Matsuri (桜祭り), il Festival dedicato.

photo credits: Pinterest, Pinterest

Il Sakura in dolcetti e manicaretti

Sakura e primavera però si celebrano anche attraverso il cibo, come da buona tradizione giapponese. Famoso è il Hanami Bentō (花見弁当), ovvero il bentō che non può mancare in un pic-nic sotto ai fiori di ciliegio. Per chi non lo sapesse, il bentō è una box per il pranzo al sacco, usatissima dai giapponesi tutto l’anno, ma che in questo periodo si declina a tema Sakura. Potrebbe capitare di trovarci dei Sakura Onigiri (桜おにぎり) ad esempio, le polpette di riso con dei Sakura salati sopra.

Tuttavia, esiste anche il tè ai fiori di ciliegio (桜茶, Sakura-cha) possibilmente abbinato al Sakura-Mochi (桜餅), tipico dolcetto di riso con pasta di fagioli rossi, avvolto in una foglia di ciliegio sotto sale. L’infuso ai Sakura tra l’altro viene offerto ai novelli sposi il giorno del matrimonio poiché ritenuto di buon auspicio. Di Wagashi (和菓子) poi – la pasticceria tradizionale giapponese – se ne trovano di svariati a tema sakura. Ancora, tra i prodotti più commerciali: come si può avere il Matcha-latte, esiste anche un Sakura-latte tutto rosa. E potremmo andare avanti ancora, ma forse meglio smettere: sennò ci viene troppa acquolina in bocca!

photo credits: kitchenbook.jp, pinterest.fr

Hanami (花見), ammirare i boccioli

Hanafubuki (花吹雪): “tempesta innevata di boccioli”. Così è definito lo spettacolo dei petali cadenti dai ciliegi in fiore, la cui pioggia colora il paesaggio in una sorta di “nevicata primaverile”. Se uno di questi petali (花びら· Hanabira) cade nel proprio bicchiere di sake, mentre si sta facendo Hanami, è un segno propiziatorio di buona salute.

Come anticipato in apertura, la parola “Hanami” indica la pratica di osservare i fiori di ciliegio (花= fiore/i, 見= guardare). Oggigiorno, i festeggiamenti per l’Hanami possono andare da semplici pic-nic a festeggiamenti più elaborati, con musica e intrattenimento. Possono avere luogo anche di notte, nel qual caso, si parla di Yozakura (夜桜) ossia di “sakura di notte”. Il risultato, potete immaginare: un evocativo Hanami notturno, fra lanterne di carta e chiaro di luna.

photo credits: power-shower.com

Tuttavia la peculiarità dell’Hanami non sta nel semplice assistere a questo spettacolo della natura: ma nell’assistervi cogliendone l’aspetto fugace. La bellezza dei boccioli consiste anche nella loro transitorietà. In chi li contempla sopraggiunge un sentimento di dolce melanconia…che la delicatezza di questi fiori è in grado di evocare quando, staccatisi dall’albero, fluttuano trasportati dal vento o da una delicata brezza, per poi posarsi a terra. Una commozione data dal realizzare che questa altro non è che la natura ultima della stessa esistenza umana: destinata, prima o poi, ad avere una fine.

“Allora vengo in questo luogo insieme ai miei antenati e mi torna un pensiero: come questi germogli stiamo tutti morendo…riconoscere la vita in ogni respiro, in ogni tazza di tè, in ogni vita che togliamo… ” [ Katsumoto Moristugu - L’Ultimo Samurai ]

photo credits: YouTube

Simbolismo del Sakura: mono no aware (物の哀れ)

Quello del Sakura è dunque un simbolismo che ha del dolce e dell’amaro, ma ciò non ci deve stupire, poiché conosciamo il sentimento giapponese del “Mono no aware”. Ossia un “pathos per le cose” caratterizzato da una delicata punta nostalgica, dovuta alla consapevolezza del loro continuo mutamento. Un concetto che il nostro Sakura incarna alla perfezione e di cui si fa inevitabilmente portavoce. La sua bellezza è incantevole ma evanescente, effimera. Perciò la contemplazione si fa dolce per via della delicatezza del fiore, ma anche malinconica…poiché consapevole della sua evanescenza. Se ne contempla così lo splendore ma con un retrogusto di tristezza. Questa in poche parole, l’essenza del Sakura.

Ancora una volta siamo di fronte a un’estetica che trascende l’aspetto esteriore. Un’esteriorità la cui bellezza aggancia gli individui, per poi portarli a una più ampia forma di contemplazione. Lo abbiamo visto bene, anche nel nostro articolo dedicato al Wabi-Sabi 侘寂. Ciò non è mai stato tanto vero, quanto nel caso dei Sakura.

I fiori di ciliegio simboleggiano dunque la transitorietà della vita e la ciclicità. Perché sbocciano sì in tutta la loro gloria ma il loro spettacolo permane per un tempo limitato. Caducità della vita, della gioventù, della bellezza: una metafora che la natura stessa ogni anno sembra voler regalare e che in Giappone sono stati particolarmente attenti a cogliere. Allo stesso tempo però sono anche simbolo di (ri)nascita e speranza...poiché ogni anno, comunque, tornano a sbocciare in tutto il loro splendore.

Meraviglia e simbolo di vitalità da una parte, estremamente fragili dall’altra: questa, la loro duplice natura. Data tale consapevolezza, il richiamo al Buddismo è inevitabile.

Simbolismo del Sakura: altri significati

Altri significati più specifici attribuiti al Sakura hanno a che vedere con il numero 5. Perciò, naturalmente, è il ciliegio classico a cinque petali quello che meglio si presta a questo tipo di simbologia. Il numero 5 richiamerebbe infatti il mito cosmogonico (sulla nascita del “cosmo”) giapponese secondo cui in origine vi erano due divinità, Izanagi e Izanami, e queste avrebbero generato cinque figli; la nascita del quinto figlio, dio del fuoco, sarebbe risultata fatale per la dea-madre Izanami. Izanagi, sconvolto, avrebbe così ucciso questo figlio, dalle cui parti si sarebbero poi originate le divinità delle montagne. Il 5 però rimanderebbe anche al concetto del Buddismo esoterico giapponese dei cinque orienti (punti cardinali più il centro) nonché ai cinque elementi acqua, fuoco, terra, etere e vuoto.

Più generalmente, i ciliegi possono venir associati anche alle nuvole semplicemente in virtù di una questione visiva: la loro fioritura in massa può ricordare le nubi in cielo. Un po’ come accade anche nell’espressione di “Hanafubuki” che abbiamo vista prima, dove il fubuki (吹雪) da solo significa “tormenta di neve”.

photo credits: Flavia

Come i Sakura, così i Samurai

Ma tornando al nostro Katsumoto-Watanabe, in realtà la sua frase si concludeva con “…questo è Bushidō”. Infatti il Sakura veniva associato anche all’ideale della via del guerriero e alla figura del samurai (侍), tanto da divenire emblema della categoria. Direte, dove sta la similitudine? Nel fatto che il fiore di ciliegio incarnava le qualità tipicamente associate al samurai (coraggio, purezza, onestà, lealtà…). Come il Sakura muore all’apice del suo splendore, così il samurai nel pieno della vitalità e della forza era pronto a morire se giungeva il suo momento. In questo senso la sua vita, per quanto grandiosa, era fragile come quella di un bocciolo di ciliegio. Egli però non temeva la morte, poiché questa era vissuta come un ultimo atto ideale e unica fine onorevole possibile, in nome di una fedeltà estrema ai propri valori.

Nel ciliegio, il bushi (guerriero) trovava il suo modello ed in esso identificava la propria vita. Proprio come il delicato fiorellino, doveva condurre la sua esistenza dando tutto sé stesso, attraverso la dedizione in ogni suo gesto, fino al suo ultimo sospiro. Tutto ciò che contava era “bruciare” sino a che fosse stato possibile, attraverso quel combustibile, che era la sua forza vitale. In tutto ciò non poteva esserci spazio per la paura della morte. Anzi: era proprio negli ultimi momenti del guerriero, che la sua bellezza risplendeva forse maggiormente.

Così i Sakura, così i bushi: proprio come nel proverbio “Hana wa sakura-gi, hito wa bushi” ( 花は桜木·人は武士 ) ossia “Tra i fiori il ciliegio, fra le persone il guerriero”. I samurai in battaglia potevano cadere sotto i colpi dell’avversario, proprio come boccioli che cadono a terra staccati dai rami per un colpo di vento o per la pioggia. Proprio come tanti piccoli boccioli, trionfanti, i samurai fiorivano; per poi andare incontro al loro destino.

photo credits: Pinterest

Di tale identificazione si servì in diversi modi anche il Giappone Imperiale secoli dopo. Fra gli altri: il Sakura venne riprodotto ai lati e, nel nome stesso, degli aeri Ōka ( 桜花 ) a simboleggiare l’atto estremo dei Kamikaze della Tokkōtai (Unità Speciale di Attacco) alla fine della II Guerra Mondiale. Gli stessi piloti, in procinto di compiere la missione suicida, pare si imbarcassero portando con sé un ramo di ciliegio.

Oggigiorno, il Sakura può simboleggiare le arti marziali.

“Donna che siede sotto i ciliegi in fiore”

photo credits: appareassociazione.blogspot.com

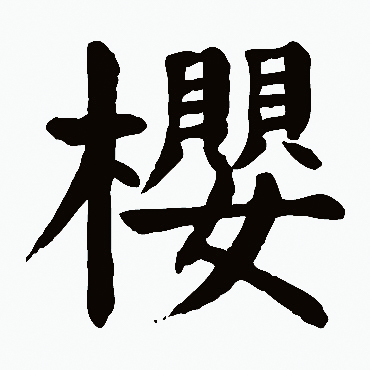

Questa, l’immagine che si potrebbe trarre–sicuramente quella che ci vedo io–osservando l’ideogramma di “sakura”. Ben lungi dall’essere, questa, la spiegazione per cui il kanji 桜presenti questa specifica forma, esso però ben si presta a tale interpretazione. Soprattutto considerata la sua forma odierna che è semplificata. Prima di lasciarci, non possiamo quindi concludere senza un attimo di parentesi sulla scrittura e sul kanji del ciliegio.

Come potete osservare nell’immagine qua sopra, l’ideogramma di Sakura 桜 si compone a sinistra del radicale 木 (=albero), a destra di tre trattini con al di sotto il carattere 女 (=donna). La particina in rosa, dite la verità: non ricorda davvero i petali di un fiore?

In realtà questa particina un tempo veniva scritta in modo più elaborato e nulla aveva a che vedere con tale significato. Si scriveva così: 櫻. Successivamente è andato incontro a un processo di semplificazione, come tanti altri ideogrammi sia in Giappone sia in Cina (da cui provengono). Tenendo conto che gli ideogrammi derivano dai pittogrammi, osserviamo nelle immagini sottostanti il nostro carattere nella sua transizione da pittogramma a ideogramma.

photo credits: shufam.hao86.com, shufa.m.supfree.net

Questa la sua transizione, per poi in tempi più moderni mutare appunto così: 櫻 🡪 桜 (in Cina invece è diventato 🡪 樱 ). Il doppio 貝貝, che precedeva i tre trattini attuali, indicava la “collana”; mentre il solo貝 ancora oggi significa “conchiglia”. Vedete quindi come, andando a indagare l’etimologia cinese, si svela la reale evoluzione storica. Tuttavia, attenzione, perché tutta la parte destra (ossia 嬰) dell’ideogramma 櫻 ha motivo di stare lì unicamente per una questione fonetica. (Non per motivi di significato, per altro diverso fra cinese a giapponese). Vale a dire, che quella parte è stata “messa” lì per conferire la pronuncia al kanji 櫻nel suo complesso.

Ma aldilà di questa breve digressione, a noi piace comunque vederla così: come una donnina sotto un albero in fiore. Giusto? Dato che oggi abbiamo a che fare con il carattere semplificato, possiamo tranquillamente concederci questa lettura del kanji che, per coincidenza, ricorda molto l’immagine di una donna sotto ai ciliegi in fiore. E sicuramente aiuta molto a ricordare l’ideogramma. Dopotutto, questo fiore richiama anche la femminilità. Non a caso Sakura, o la variante Sakurako (桜子o 櫻子), sono nomi femminili alquanto diffusi in Giappone.

photo credits: pinterest.it

Japan History: Azai Nagamasa

Azai Nagamasa (1545 - 26 settembre 1573) era un daimyō giapponese, figlio di Azai Hisamasa, dal quale ereditò la leadership del clan nel 1560 quando Hisamasa fu costretto a dimettersi in favore di suo figlio.

Azai Nagamasa, il capo del clan Azai

Autore: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Nagamasa divenne uno dei nemici di Nobunaga nel 1570 a causa dell'alleanza degli Azai con il clan Asakura, combattendo contro di lui in importanti battaglie tra cui la battaglia di Anegawa. Nagamasa e il suo clan furono distrutti da Nobunaga nell'agosto 1573, e lui commise seppuku durante l'assedio del castello di Odani.

Conflitto con Oda Nobunaga

Non solo acerrimo nemico di Oda Nobunaga, Azai Nagamasa divenne anche suo cognato, perchè nel 1564 sposò sua sorella Oichi. Oda Nobunaga cercava di instaurare relazioni con il clan Azai a causa della loro posizione strategica tra le terre del clan Oda e la capitale, Kyoto.

Il grande conflitto iniziò quando nel 1570, Oda Nobunaga dichiarò guerra alla famiglia Asakura assediando il castello di Kanegasaki. Gli Asakura e gli Azai erano stati alleati fin dai tempi antichi. In questa guerra, contrariamente ai molti che volevano onorare l'alleanza con gli Asakura, Nagamasa preferì rimanere neutrale, schierandosi con Nobunaga. Alla fine, il clan Azai scelse di onorare l'antica alleanza con gli Asakura e venne in loro aiuto. Per questo motivo l'esercito di Nobunaga, che stava marciando sulle terre degli Asakura, si ritirò verso Kyoto. Tuttavia, nel giro di pochi mesi le forze di Nobunaga erano di nuovo in marcia, ma questa volta marciarono sulle terre degli Azai.

La battaglia di Anegawa

Nell'estate del 1570, Oda Nobunaga tornò all’attacco insieme a Tokugawa Ieyasu e ad un'armata di circa 30000 uomini nella provincia di Omi contro gli Azai e gli Asakura. La battaglia di Anegawa si svolse su due fronti, Oda contro Azai, Tokugawa contro Asakura. Anche se in inferiorità numerica, le truppe di Nagamasa riuscirono a tenere a bada le truppe degli Oda e sembrava quasi che la vittoria fosse assicurata, ma quando Tokugawa Ieyasu, dopo aver sconfitto gli Asakura venne in aiuto a Nobunaga, ribaltò la situazione.

La morte

Nel corso dei due anni successivi gli Azai furono sotto costante attacco da parte degli Oda che arrivarono ad assediare il castello della capitale, Odani nel 1573 nel famoso assedio di Odani. Proprio durante questo periodo gli Azai sono visti come vagamente allineati con numerose forze anti-Oda, compresi gli Asakura, i Miyoshi, i Rokkaku e diversi complessi religiosi.

Senza nessuna via di scampo, Nagamasa compì seppuku nell'agosto del 157e insieme a suo padre Hisamasa, inviando Oichi e le sue tre figlie da Nobunaga che decise di risparmiarle. Cosa che non accadde con l’unico erede maschio di Nagamasa, Manpukumaru, che fu giustiziato dal generale Toyotomi Hideyoshi per ordine di Nobunaga.

Oda Nobunaga si assicurò che sua sorella Oichi, non fosse informata di questo, ma alla fine lei arrivò a questo sospetto.

Sembra che Nobunaga nutrisse un forte rancore nei confronti di Nagamasa a causa del suo presunto tradimento, anche se fu lui a rompere l'accordo per primo. si dice anche che che Nobunaga fece laccare i teschi di Nagamasa, Hisamasa e del capo degli Asakura in modo che potessero essere usati come tazze, ma questo fatto non solo non è storicamente accurato, ma potrebbe essere anche inventato per screditare maggiormente la reputazione di Nobunaga.

photo credits: wikipedia.org

C’è da aggiungere che le tre figlie di Nagamasa ebbero una grande importanza, partendo dal fatto che andarono in spose ad uomini molto famosi:

- Chacha, o Yodo dono, fu la seconda moglie di Toyotomi Hideyoshi e madre del suo erede Hideyori.

- Hatsu, sposò il daimyo Kyōgoku Takatsugu.

- Oeyo, o Sūgen'in, fu moglie del secondo shōgun dei Tokugawa, Hidetada, e madre del suo successore Iemitsu.