Japan Modern Culture: The New Tsukiji Fish Market opens and is called Toyosu Market

photo credit: nika-88 on flickr & karipkarip on flickr

All the fans of Japan have heard of the Tsukiji Fish Market at least once. Tsukiji's wholesale fish market (in Japanese 築地市場, Tsukiji shijō) was the largest fish market in the world. It was in Tokyo, in the Tsukiji district, and it moved to the Toyosu area last October.

Visited every year by thousands of tourists, today's Toyosu (Tsukiji) Fish Market hosts a number of workers ranging from 60,000 to 65,000, including accredited sellers, administrative staff and workers.

The Tsukiji Fish Market was, and still is, a showcase on an important element of Japanese gastronomic culture and the nation's economy. Considered a national institution, from October it finally established its roots in Toyosu's new space, retiring after 80 years from the space in the Tsukiji district. The Tokyo fish market continues to maintain its record as the largest wholesale fish market in the world.

Tsukiji Fish Market has always been one of the symbols of the iconic relationship between Japanese cuisine and the ocean. It is not rare to find international chefs and restaurateurs from across the city walking among the auctions every morning and being bewitched by the atmosphere of this place.

photo credit: yuichi38 on flickr & 584laurel on flickr

History

The history of the Tsukiji is equally impressive. Over 500 species of fish sold daily, including some really expensive sushi cuts, 700 thousand tons of product sold each year, more than 12 million euros in daily turnover.

Already replacing the previous market in the Nihonbashi area destroyed by the Great Kanto earthquake in 1923, the Tzukiji fish market opened its doors in 1935. With its hundreds of stalls, the market is famous for selling fish that varies from scampi to whale, but especially for the daily auction of bluefin tuna, sold for thousands of dollars each. A tradition that also continues in Toyosu's new market is also that of the New Year's auction where restaurateurs compete against each other to pay the highest price for the first tuna on January 1st each year.

photo credit: jpellgen on flickr & thisisinsider.com

The market opens at 5 am and is also very popular with tourists. If you want to take advantage of your jet lag, be sure to get in line to be selected in the small group of visitors who are allowed to watch the tuna auction.

The tuna appear in various sizes and, during the auction, they are placed on the ground, in order, still frozen. Each cut is provided with a tag that indicates its weight, quality and provenance, and comes without head and tails so as to be able to view the color of the meat.

At the end of the auction, all visitors can put themselves in even longer queues to see those in charge of cutting and preparing ready-to-use tuna slices. It is here that you can see and taste the classic sushi cut and the best sashimi you can eat.

photo credit: thisisinsider.com & jpellgen on flickr

Where is the Toyosu Fish Market now?

IThe New Tsukiji Fish market, now renamed Toyosu Fish Market, is located near Shijomae Station on the Yurikamome Line, in Tokyo's Koto district, about 2 km east of Tsukiji. It is housed in 3 interconnected buildings (two for the sale of fish and one for the sale of fruit and vegetables). The buildings are connected directly to the station with a covered overpass, making it perfect for any climate. Toyosu is almost twice the size of the old Tsukiji market, about 40.7ha which allows it to maintain its status as the world's largest fish market.

photo credit: CNN.com & thisisinsider.com

Admission to the Toyosu Fish Market

Entry to the Toyosu Fish Market is free and you can watch auctions from dedicated platforms. You just need a visitor pass to enter the buildings and you can also taste all the delicious dishes in the restaurants, most of which was transplanted by the old Tsukiji.

There is not much else around there, but if you want to stay in the area, you can go explore the nearby Odaiba. Furthermore, it is said that in 2022 the Senkyaku Banrai will be opened, a street dedicated to shopping, a major part of a project to make the community more livable and lively.

photo credit: falloutx & thisisinsider.com

Japan History: Italy & Japan 150 Years of Friendship

Italy & Japan 150 Years of Friendship

Photo Credits: Ambasciata del Giappone

150 years of friendship between Italy and Japan was celebrated in 2016.

This relationship between these two countries dates back to 1866, on the 4th of July, when an Italian military ship sent by King Vittorio Emanuele II arrived in Yokohama port to offering a treaty of friendship and commerce.

Back then, both countries had a common goal. They were eager to close the economic distance that separating them from the other more influential and powerful countries in those days.

Photo Credits: L'inviato Speciale

An alliance for better or for worse

After the end of First World War, Italy and Japan experienced same outcome. They both won the conflict, however both felt "betrayed" following the Versailles Treaty. Italy suffered from the indignation of not getting all the territories that it expected while Japan suffered from diplomatic defeats in the rejection of Japan's bid for a racial equality. Moreover, the two countries were experiencing critical post-conflict economic situations that would have led towards a totalitarian regime of the Second World War.

In 1937, Italy went against the Russian’s communist politics, like how Japan did when they signed the Anti-Komintern Pact with Hitler's Germany. In the following year, the fascist national party landed in Japan, and Mussolini's works were translated into Japanese. The Germany-Japan-Italy Tripartite Agreement was signed, creating the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo alliance. In that period Mussolini made several visits to Japan.

All those who refused to join the fascist party in Japan were interned in the camps at Nagoya.

The atomic bombs dropped to Nagasaki and Hiroshima hit Japan hard and both Italy and Japan had to recover from the tragedies caused by the war. At the end of the Second World War, both countries underwent radical transformations.

Photo Credits: Il turista curioso.it

An eternal bridge

The bridges built between the two countries continued to multiply over the years. In 1970, the first intercontinental television link between NHK and RAI broadcasters led to new cultural exchanges, allowing the products and lifestyles, from food to martial arts and increasingly intense linguistic exchanges, to grow ever closer.

In recent times, the mutual influence between the two nations also translated into architectural works.

Architect Kenzo Tange, who gave Tokyo its present-day landscape, designed numerous buildings in Italy, like the towers of the Bologna exhibition center and the business center of Naples, while Renzo Piano designed the Osaka airport and Ushibuka Bridge.

These days, Japan and Italy continue to enjoy cordial and friendly exchanges, growing and strengthening their relationship with each other as they always have through the past 150 years.

Metropolitan Governement Building Shinjuku Park Tower

Photo Credits: Japan italy Bridge

Ushibuka bridge, Photo Credits: Wikipedia.org

Japan History: Forty-seven Ronin

FORTY-SEVEN RŌNIN

A band of rònin (samurai without leader) avenged the death of their master. The event is known as the revenge of the forty-seven rōnin (四 十七 士 Shi-jū-shichi-shi, forty-seven samurai), also as the Akō incident (Akō jiken) or Akō's revenge, and is considered an historical event in Japan.

Photo Credits: Wikipedia.org

The story tells of a group of samurai remaining without leader after their daimyō Asano Naganori was forced to execute seppuku for assaulting Kira Yoshinaka, a court official whose title was Kōzuke no suke. After waiting and planning for a year, the rōnin avenged their master's honor by killing Kira. In turn, they were forced to commit seppuku because of the murder crime. This story has been made popular in Japanese culture as a symbol of loyalty, sacrifice, perseverance and honor, values people should look for in their daily lives. The story's popularity grew during the Meiji era, when Japan underwent rapid modernization, and the legend became important in national heritage and identity.

The fictional stories of the Forty-seven Rönin are known as Chūshingura. The story has been made popular in numerous shows, including bunraku and kabuki. Because of the shogunate laws of censorship in the Genroku era, which prohibited the portrayal of current events, the names were changed. The first Chūshingura was written about 50 years after the event.

The censorship laws had subsided a bit 75 years later, at the end of the eighteenth century, when Isaac Titsingh recorded for the first time the history of the forty-seven rōnin as one of the significant events of the Genroku era. It continues to be popular in Japan, and every year on December 14, in the Sengakuji Temple, where Asano Naganori and the rōnin are buried, a festival is held to commemorate the event.

In 1701, two daimyōs, Asano Takumi-no-Kami Naganori and Lord Kamei Korechika of the Tsuwano domain, were ordered to organize a reception for the emperor's messengers to the castle of Edo, during their sankin-kōtai service to the shōgun .

Asano and Kamei were to receive instructions on the necessary court code from Kira Kozuke-no-Suke Yoshinaka, a powerful Tokugawa Tsunayoshi shogunate official. He got very angry with them, either because of the insufficient gifts they offered him, or because they could not provide the bribe requests. Other sources describe him as naturally rude and arrogant or corrupt, this behavior offended Asano, a devoutly moral confucian. According to some reports, it seems that Asano was not familiar with the complexities of the shogunate court and had not shown the right amount of deference to Kira.

Initially, Asano endured everything stoically, while Kamei raged and prepared to kill Kira to avenge the insults. However, Kamei's advisors avoided the disaster for their lord and teamed up by collecting and giving Kira a big bribe; Kira then began to treat Kamei well and this contributed to calm him down.

However, Kira continued to treat Asano hard to the point of insulting him, calling him a country farmer without good manners, and Asano eventually stopped holding back. At Matsu no Ōrōka, the main hallway of Honmaru Goten residence, Asano lost his temper and attacked Kira with a dagger, wounding him in the face. They had to intrude the guards to separate them.

Kira's injury was not severe, however attacking a shogunate official within the boundaries of the shogun's residence was considered a serious crime. Any violence was completely forbidden in Edo's castle. Akō's daimyō had used his dagger inside Edo Castle, and for this crime, he was ordered to make seppuku. Asano's assets and lands had to confiscated after his death, his family had to be ruined, and his servants had to become rōnin,according to the general rule of the time.

The news arrived to Ōishi Kuranosuke Yoshio, Asano's chief adviser, who took over the command and transferred the Asano family before delivering the castle to government agents.

Forty-seven men, among the over 300, and especially their leader Ōishi, refused to allow their lord to take revenge. They teamed up in secret swearing to avenge their master and kill Kira, even though they knew they would be severely punished for that.

Kira was however well guarded and his residence had been protected. The ronin realized they should not rise Kira’s and other shogunate authorities suspicion, so they dispersed and became merchants and monks.

Ōishi took residence in Kyoto and began to frequent brothels and taverns. Kira feared a trap and sent spies to monitor the former servants of Asano.

One day, Ōishi, returning home drunk, fell down and fell asleep in the street. A man, Satsuma, was so enraged by this behavior of a samurai that he began to insult him, kicking him in the face and spitting on him.

Not long after, Ōishi divorced from his faithful wife after twenty years of marriage. He did not want to harm her her when the rōnin would have taken their revenge. He sent her away with their two younger children to live with her parents. He asked their eldest son, Chikara, whether he would have preferred to stay and fight or leave. Chikara stayed with his father.

Ōishi started to behave in a strange way and very different from the samurai style. He attended geishas (particularly Ichiriki Chaya), he drank every night and spoke obscenely in public. Ōishi's servants bought a geisha, hoping she would calm him down. All this was a plot to free Ōishi from Kira’s spies.

Kira's agents reported all this to Kira. Kira was then convinced he was safe from the servants of Asano, considering one year and a half elapsed he judged them without the courage to avenge their master. Thinking they were harmless, he lowered his guard.

The rest of the rōnin gathered in Edo, and in their roles as merchants and workers, had access to Kira's house, becoming familiar with the environment and people. Okano Kinemon Kanehide married the daughter of one of the builders of the house, managing to get the project. All this was reported to Ōishi. Others gathered and transported their weapons to Edo.

After two years, Ōishi was convinced that Kira was completely unaware, and everything was ready, He left Kyoto, avoiding the spies watching him, and joined the whole band gathered in a secret meeting place in Edo to renew their oaths.

On January 30, 1703 early in the morning, Ōishi and another rōnin attacked Kira Yoshinaka's home in Edo. According to a carefully defined plan, they would divide into two groups and would attack armed with swords and bows. A group, led by Ōishi, would attack the main gate; the other, led by his son, Ōishi Chikara, would attack the house through the back gate. A drum would sound the simultaneous attack, and a whistle would signal Kira's death.

Once dead, they planned to cut Kira's head and place it as an offering on their master's grave. They would then wait for their planned death sentence. All this had been agreed during a final dinner, during which Ōishi had asked to be careful and save women, children and other defenseless people.

Photo Credits: Wikipedia.org

Ōishi had four men at the fence and entered the caretaker's house, capturing and binding the guard. He then sent messengers to all neighboring houses, to explain that they were not robbers, but servants avenging the death of their master, and that no harm would be done to others: the neighbors were all safe. One of the rōnin climbed up to the roof and announced aloud to the neighbors that the matter was an act of revenge. The neighbors, who hated Kira, were relieved and did nothing to thwart the plan.

Dopo aver appostato gli arcieri per impedire agli abitanti di chiedere aiuto, Ōishi suonò il tamburo per iniziare l'attacco. Ten of the Kira keepers prevented the attack on the house from the front, but Chiishi Chikara's side is attacked from the back.

Following setting up of the archers to prevent house residents asking for help, Oishi played the drum to start the attack. Ten of the Kira keepers prevented the attack of the house from the front, allowing Chiishi Chikara to attack from the back.

Kira, terrified, took refuge in a closet on the veranda, along with his wife and his maids. The rest of his servants, sleeping in the barracks outside, tried to enter the house to save him. After passing the defenders at the front of the house, the two parts led by father and son joined and fought the servants who were entering. The latter, realizing they were about to lose, tried to ask for help, but their messengers were killed by the archers already set up to prevent this.

After a fierce fight, the last of Kira's servants was defeated; the ronin killed 16 men of Kira and wounded 22, including his nephew. However, no signs about Kira. They searched the house, they heard women and children cry. They were beginning to despair, when Ōishi checking Kira's bed, discovered that it was still warm, so he knew Kira could not be far away.

In a courtyard hidden in the back, they discovered a man who was hiding and was easily disarmed.

He refused to say who he was, the ronin however knew he was Kira and they whistled. The rōnin gathered and Ōishi, with a lantern, confirmed he was indeed Kira and as a final proof, he discovered on his head a scar of Asano's attack.

Ōishi knelt, and in consideration of Kira’s high degree, he respectfully addressed him, telling him that they were Asano's servants, come to avenge him as the true samurai should, and inviting him to die like a true samurai should , killing himself. Ōishi said he would act like a kaishakunin ("second", the one beheading a person who committed seppuku to spare him being unworthy of death) and offered him the same dagger that Asano used to kill himself.

However, no matter how much they begged him, Kira crouched, wordlessly trembling. Seeing that it was useless to continue, Ōishi ordered the other rōnin to killed him by cutting off his head with the dagger.

They turned off all the lamps and fires in the house and left with Kira's head.

One of the rōnin, Terasaka Kichiemon, was ordered to go to Akō and report that their revenge had been completed. (Although the role of Kichiemon as a messenger is the most accepted version of the story, other sources see him escape before or after the battle).

The rōnin, on their way back to Sengaku-ji, stopped in the street to rest and refresh themselves.

Photo Credits: Wikipedia.org

At dawn, they quickly brought Kira's head from his residence to the tomb of their lord in the temple of Sengaku-ji, marching for about ten kilometers across the city, causing a great sensation on the road. The story of revenge spread rapidly and everyone praised them and offered them refreshment during their journey.

Arrived at the temple, the remaining 46 rōnin (all except Terasaka Kichiemon) washed Kira's head in a well, and set it down with the dagger in front of Asano's tomb. They then offered prayers to the temple and gave the temple monk the remaining money, asking him to bury them decently and offer prayers for them. The group was divided into four parts and placed under the guard of four different daimyōs.

Two friends of Kira came to take his head for burial.

Edo shogunate’s officials were embarrassed. The samurai had followed the precepts by avenging their lord's death; however they also challenged the shogunate's authority by executing revenge, which was forbidden. As expected, the rōnin were sentenced to death for Kira's murder; the shogun eventually ordered them to commit honorably seppuku instead of having them executed as criminals. It is known that each of the assailants ended his life in a ritual manner. Ōishi Chikara, the youngest, was only 15 years old on the day of the attack, and only 16 the day he committed seppuku.

Each of the 46 rōnin killed himself on February 4, 1703. The forty-seventh ronin, identified as Terasaka Kichiemon, eventually returned from his mission and was forgiven by the shogun (it is said because of his youth). He lived until the age of 87, dying in 1747, and was buried with his companions. The assailants who died of seppuku were buried in the ground of Sengaku-ji, in front of the tomb of their master.

Their clothes and weapons are still kept in the temple, along with the drum and the whistle; their armor was all homemade, since they did not want to raise suspicion by buying one.

The tombs became a place of veneration and people gathered there in prayer. They were visited by many people over the years since the Genroku era. One of the visitors, Satsuma who laughed and spat at Ōishi in Kyoto, begged forgiveness for his actions and for thinking that Ōishi was not a true samurai. He then committed suicide and was buried near the river.

Although revenge was seen as an act of loyalty, there was actually a second goal: re-establishing Asano's lordship and finding a place where their fellow samurai could serve. Hundreds of samurai who served Asano had been left without work, and many were unable to find a job, as they had served under a dishonored family. Many lived as farmers or did simple crafts to make their living. The revenge of the forty-seven ronin erased their names and many of the unemployed samurai found work.

Photo Credits: Wikipedia.org

The Forty-seven Rōnin

Ōishi Kuranosuke Yoshio/Yoshitaka (大石 内蔵助 良雄)

Ōishi Chikara Yoshikane (大石 主税 良金)

Hara Sōemon Mototoki (原 惣右衛門 元辰)

Kataoka Gengoemon Takafusa (片岡 源五右衛門 高房)

Horibe Yahei Kanamaru/Akizane (堀部 弥兵衛 金丸)

Horibe Yasubei Taketsune (堀部 安兵衛 武庸)

Yoshida Chūzaemon Kanesuke (吉田 忠左衛門 兼亮)

Yoshida Sawaemon Kanesada (吉田 沢右衛門 兼貞)

Chikamatsu Kanroku Yukishige (近松 勘六 行重)

Mase Kyūdayū Masaaki (間瀬 久太夫 正明)

Mase Magokurō Masatoki (間瀬 孫九郎 正辰)

Akabane Genzō Shigekata (赤埴 源蔵 重賢)

Ushioda Matanojō Takanori (潮田 又之丞 高教)

Tominomori Sukeemon Masayori (富森 助右衛門 正因)

Fuwa Kazuemon Masatane (不破 数右衛門 正種)

Okano Kin'emon Kanehide (岡野 金右衛門 包秀)

Onodera Jūnai Hidekazu (小野寺 十内 秀和)

Onodera Kōemon Hidetomi (小野寺 幸右衛門 秀富)

Kimura Okaemon Sadayuki (木村 岡右衛門 貞行)

Okuda Magodayū Shigemori (奥田 孫太夫 重盛)

Okuda Sadaemon Yukitaka (奥田 貞右衛門 行高)

Hayami Tōzaemon Mitsutaka (早水 藤左衛門 満尭)

Yada Gorōemon Suketake (矢田 五郎右衛門 助武)

Ōishi Sezaemon Nobukiyo (大石 瀬左衛門 信清)

Isogai Jūrōzaemon Masahisa (礒貝 十郎左衛門 正久)

Hazama Kihei Mitsunobu (間 喜兵衛 光延)

Hazama Jūjirō Mitsuoki (間 十次郎 光興)

Hazama Shinrokurō Mitsukaze (間 新六郎 光風)

Nakamura Kansuke Masatoki (中村 勘助 正辰)

Senba Saburobei Mitsutada (千馬 三郎兵衛 光忠)

Sugaya Hannojō Masatoshi (菅谷 半之丞 政利)

Muramatsu Kihei Hidenao (村松 喜兵衛 秀直)

Muramatsu Sandayū Takanao (村松 三太夫 高直)

Kurahashi Densuke Takeyuki (倉橋 伝助 武幸)

Okajima Yasoemon Tsuneshige (岡島 八十右衛門 常樹)

Ōtaka Gengo Tadao/Tadatake (大高 源五 忠雄)

Yatō Emoshichi Norikane (矢頭 右衛門七 教兼)

Katsuta Shinzaemon Taketaka (勝田 新左衛門 武尭)

Takebayashi Tadashichi Takashige (武林 唯七 隆重)

Maebara Isuke Munefusa (前原 伊助 宗房)

Kaiga Yazaemon Tomonobu (貝賀 弥左衛門 友信)

Sugino Jūheiji Tsugifusa (杉野 十平次 次房)

Kanzaki Yogorō Noriyasu (神崎 与五郎 則休)

Mimura Jirōzaemon Kanetsune (三村 次郎左衛門 包常)

Yakokawa Kanbei Munetoshi (横川 勘平 宗利)

Kayano Wasuke Tsunenari (茅野 和助 常成)

Terasaka Kichiemon Nobuyuki (寺坂 吉右衛門 信行)

Japan History: Date Masamune

Date Masamune

Photo Credits: samurai-archives.com

Date Masamune (伊達 政宗, September 5, 1567 – June 27, 1636) was a regional ruler of Japan's Azuchi–Momoyama period (last part of the Sengoku period) through early Edo period. Heir to a long line of powerful daimyōs in the Tōhoku region, he went on to found the modern-day city of Sendai. An outstanding tactician, he was made all the more iconic for his missing eye, as Masamune was often called dokuganryū (独眼竜), or the "One-Eyed Dragon of Ōshu".

Early life

Date Masamune was born as Bontemaru (梵天丸) in Yonezawa Castle (in modern Yamagata Prefecture). He was the eldest son of Date Terumune, a lord of the Rikuzen area of Mutsu, and Yoshihime, a daughter of Mogami Yoshimori, daimyo of the Dewa province. He recieved the name Tojirou (藤次郎) Masamune in 1578, and the following year he married Megohime, the daughter of Tamura Kiyoaki, lord of Miharu castle, in Mutsu Province. At the age of 14, in 1581, Masamune led his first campaign, helping his father fight the Sōma family. In 1584, at the age of 17, Masamune succeeded his father, Terumune, who chose to retire from his position as daimyō.

Masamune's army was recognized by its black armor and golden headgear. Masamune himself is known for a few things that made him stand out from other daimyōs of the time. In particular, his famous crescent-moon-bearing helmet won him a fearsome reputation.

As a child, smallpox robbed him of sight in his right eye, though it is unclear exactly how he lost the organ entirely. Various theories behind the eye's condition exist. Some sources say he plucked out the eye himself when a senior member of the clan pointed out that an enemy could grab it in a fight. Others say that he had his trusted retainer Katakura Kojūrō gouge out the eye for him, and this, together with his fearsome temperament, made him the 'One-Eyed Dragon' of Ōshu.

Military campaign

The Date clan had built alliances with neighboring clans through marriages over previous generations, but local disputes remained commonplace. Shortly after Masamune's succession in 1584, a Date retainer named Ōuchi Sadatsuna defected to the Ashina clan of the Aizu region. Masamune declared war on Ōuchi and the Ashina for this betrayal, and started a campaign to hunt down Sadatsuna. Many clans, even formerly amicable allies, fell. In the winter of 1585, one of these allies, Hatakeyama Yoshitsugu, felt defeat was approaching and chose to surrender to the Date. Masamune agreed to accept the surrender, but on the heavy condition that the Hatakeyama give up most of their territory to the Date. This resulted in Yoshitsugu kidnapping Masamune's father, Terumune, during their meeting in Miyamori Castle, where Terumune was staying at during the time. The incident ended with the death of Terumune, while fleeing Hatakeyama men clashed with the Date troops near the Abukuma river.

A general war ensued between the Date and Hatakeyama, the latter drawing on support from the Satake, Ashina, Soma, and other local clans. The allies marched to within a half-mile of Masamune's Motomiya-jo, assembling some 30,000 troops for the attack. Masamune, having only 7,000 warriors, prepared a defensive strategy, relying on the series of forts that guarded the approaches to Motomiya. The fighting began on the 17th of November, and did not progress well for the Date. Three of his valuable forts were taken, and one of his chief retainers, Moniwa Yoshinao, was killed in a duel with an opposing commander. The attackers pressed towards the Seto River, which was the last obstacle between them and Motomiya. Date attempted to turn them back at the Hitadori Bridge, but was driven back. Masamune brought his remaining forces within Motomiya's walls, and prepared for what would surely be a gallant but futile last stand. But the next morning,the main enemy contingent picked up and marched away. These were Satake Yoshishige's men. Their lord had received word that in his absence the Satomi had attacked his lands in Hitachi. Apparently this left the allies with fewer men than they believed possible to bring down Motomiya, for they too retreated by the end of the day. This brush with utter defeat was likely a factor in turning Masamune into the renowned general he would one day be known as. In the wake of the battle, peace was struck with the Hatakeyama and Soma, although this was to prove short-lived.

In 1589, Date defeated the Soma, and bribed an important Ashina retainer, Inawashiro Morikuni, over to his side. He then assembled a powerful force and marched straight for the Ashina's headquarters at Kurokawa. The Date and Ashina forces met at Suriagehara on 5 June when Masamune's forces overcame the faltering Ashina ranks, breaking them. Unfortunately for the Ashina, Date men had destroyed their avenue of escape, a bridge over the Nitsubashi River, and those who did not drown attempting to swim to safety were mercilessly put to the sword.

By the battle's end, Masamune could count something like 2,300 enemy heads in one of the more bloody and decisive battles of the Sengoku period. Masamune then proceeded to make the rich Aizu domain his base of operations.

However, this would be Date Masamune's last expansionist adventure.

Photo credits: wattention.com

Statua di Date Masamune nella città di Sendai sulle rovine del Castello di Sendai,

Service under Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu

In 1590, Toyotomi Hideyoshi seized Odawara Castle and compelled the Tōhoku-region daimyōs to participate in the campaign. Although Masamune refused Hideyoshi's demands at first, he had no real choice in the matter since Hideyoshi was the virtual ruler of Japan. However, the delay infuriated Hideyoshi. Expecting to be executed, Masamune, wore his finest clothes showing no fear in facing his angry overlord. But Hideyoshi spared his life, saying that "He could be of some use".

Following the conclusion of the siege, Masamune was forced to relinquish his newly won holdings in Aizu and was give Iwatesawa and the surrounding lands. Lands that would have earned him less, though. Masamune moved there in 1591, rebuilt the castle renaming it Iwadeyama, and encouraged the growth of a town at its base. Masamune stayed at Iwadeyama for 13 years and turned the region into a major political and economic center.

He and his men served with distinction in the Korean invasions under Hideyoshi and, after Hideyoshi's death, he began to support Tokugawa Ieyasu, apparently at the advice of Katakura Kojūrō. For this reason Masamune was awarded with the lordship of the huge and profitable Sendai Domain, which made Masamune one of Japan's most powerful daimyōs. Tokugawa had promised Masamune a one-million koku domain but, even after substantial improvements were made, the land only produced 640,000 koku. And most of the earnings were used to feed the Edo region. In 1604, Masamune, accompanied by 52,000 vassals and their families, moved to what was then the small fishing village of Sendai. He left his fourth son, Date Muneyasu, to rule Iwadeyama.

Masamune would turn Sendai into a large and prosperous city.

Although Masamune was a patron of the arts and sympathized with foreign causes, he was also an aggressive and ambitious daimyō. When he first took over the Date clan, he suffered a few major defeats from powerful and influential clans such as the Ashina. These defeats were arguably caused by recklessness on Masamune's part.

Being a major power in northern Japan, Masamune was naturally viewed with suspicion. Toyotomi Hideyoshi had reduced the size of his land after his tardiness in coming to the Siege of Odawara against Hōjō Ujimasa. Later, Tokugawa Ieyasu increased the size of his lands again, but was constantly suspicious of Masamune and his policies.

Although Tokugawa Ieyasu and other Date allies were always suspicious of him, Date Masamune for the most part served both Toyotomi and Tokugawa loyally. He took part in Hideyoshi's campaigns in Korea, and in the Osaka campaigns too. When Tokugawa Ieyasu was on his deathbed, Masamune visited him and read him a piece of Zen poetry.

Masamune was highly respected for his ethics, and a still-quoted aphorism is, "Rectitude carried to excess hardens into stiffness; benevolence indulged beyond measure sinks into weakness."

Patron of culture and Christianity

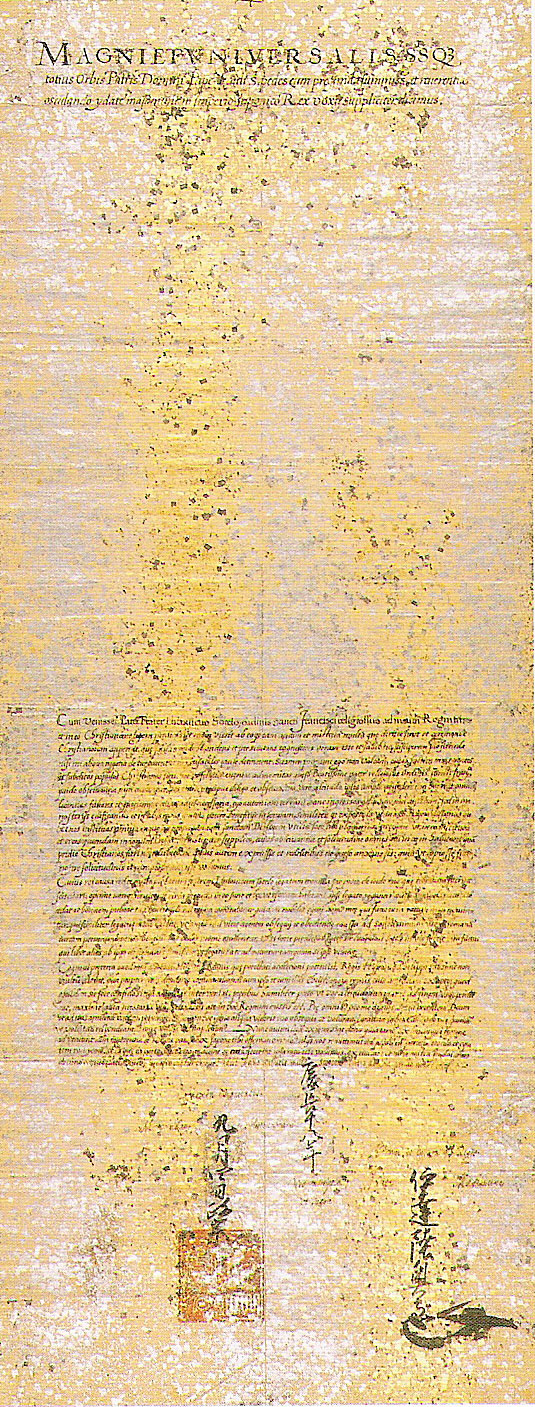

Photo Credits: wikimedia.org

Una lettera scritta da Masamune al Papa Paolo V

Masamune expanded trade in the otherwise remote, backwater Tōhoku region. Although initially faced with attacks by hostile clans, he managed to overcome them after a few defeats. In the end, he eventually ruled one of the largest fiefdoms of the later Tokugawa shogunate. He built many palaces and worked on many projects to beautify the region. For 270 years, Tōhoku remained a place of tourism, trade and prosperity. Matsushima, for instance, a series of tiny islands, was praised for its beauty and serenity by the wandering haiku poet Matsuo Bashō.

Other than being known to have encourage foreigners to come to his land, Masamune also showed sympathy for Christian missionaries and traders in Japan. In addition to allowing them to come and preach in his province, he also released the prisoner and missionary Padre Sotelo from the hands of Tokugawa Ieyasu. Date Masamune allowed Sotelo as well as other missionaries to practice their religion and win converts in Tōhoku.

Moreover, he funded and promoted an expedition to establish diplomatic relations with the Pope in Rome, even though he was likely motivated at least in part by a desire for foreign technology. In this, he was similar to other lords, such as Oda Nobunaga. For the expedition he ordered the building of the exploration ship Date Maru or San Juan Bautista, using European ship-building techniques. He sent one of his retainers, Hasekura Tsunenaga, Sotelo, and an embassy numbering 180 people on a successful voyage that included places as the Philippines, Mexico, Spain and Rome, of course. Previously, Japanese lords had never funded this sort of venture, so it was probably the first of such voyages. At least five members of the expedition stayed in Coria, Spain, to avoid the persecution of Christians in Japan. 600 of their descendants, with the surname Japón (Japan), are now living in Spain.

When the Tokugawa government banned Christianity, Masamune had to obey the law reversing his position, and though disliking it, let Ieyasu persecute Christians in his domain. However, some sources suggest that Masamune's eldest daughter, Irohahime, was a Christian.

Photo credits: it.wikipedia.org

Replica del galeone Date Maru, o San Juan Bautista, a Ishinomaki, Giappone

Masamune had 16 children, two of whom were illegitimate, with his wife and seven concubines. He died in 1636 at the age of 69. In October 1974, Date Masamune’s grave was opened. Inside, along with his remains, archaeologists discovered his tachi sword, a letter box with a paulownia crest, and his armor. From the study of those remains, they determined Masamune to have stood 159.4cm tall, and having type B blood.

As legendary warrior and leader, Masamune is the character of various Japanese dramas. He was also played by the famous Ken Watanabe in the popular 1987 NHK series Dokuganryū Masamune.

Photo credits: wikimedia.org

La tomba di Masamune al mausoleo di Zuihōden

Japan Folklore: Kanamara Matsuri

Kanamara Matsuri

Photo credits: pictureasiastudio.wordpress.com

The festival of the "Steel Phallus"

The Kanamara Matsuri (かなまら祭り) is often welcomed by foreigners as yet another quirk from Japan, but in fact, the origins of this festival are very old and they are related to Shinto religion.

It all began in the Edo period, in 1603, when the town of Kawasaki was the destination for travelers who found their enjoyment in tea houses and, in private, entertained themselves with prostitutes. Prostitutes that used to visit the Kanayama temple to pray for protection from sexually transmitted diseases.

There is also a legend that revolves around the name of the Kanamara Matsuri, according to which a demon with sharp teeth lived in the vagina of a young girl. Any man who had intimate relations with her ended up irreparably castrated. Her husband too fell victim of the demon on the first wedding night and the girl, now desperate, asked for help to a blacksmith. The man forged an iron phallus that broke the demon's teeth and freed the woman from the curse. To celebrate, a small Shinto temple was erected becoming the place where the iron phallus is still venerated today.

The tradition was lost in late 1800s but, in the 1970s, chief priest Hirohiko Nakamura decided to revive the lost festival.

For centuries, the Kanayama temple has been the place where couples pray for a child, or where to pray for luck in business, an easy delivery or simply family harmony.

Photo credits: matome.naver.jp

3 Mikoshi and no preconcept

Every year, on the first Sunday of April, priests of the Kanayama Jinja in Kawasaki organize this festival.

The parade opens up with a shinto ceremony at the shrine where sake and fried fish are distributed to all visitors as a wish for good luck. Finally, the big pink penis placed on an altar is brought to the temple. At this point, the parade actually starts following three mikoshi, each containing a huge phallus. The first one stands erect and is made of a polished black metal. The second is an old wooden one, ancient and gnarled, and both are transported by carriers of the shrine who sing along the procession. The third one is entrusted to a joso group: they are members of a cross-dressing club called Elizabeth Kaikan. Its members, with their bright make-up and colored wigs, move the mikoshi in the air preening for the cameras.

After the parade, everyone gather to enjoy street-food, sexual-themed competitions and the cheerful atmosphere. Among the proposed challenges there is the sculpture contest, with sculpture that must have a phallic shape of course, or a rodeo with a big rotating penis. The festival is attended both by locals and tourists that, for the occasion, leave aside all taboos. The great majority of people wear all sorts of extravagant things, as fake penis-noses, while eating foods of the same shape.

We can also come across young women posing for photos while riding on swings that for the occasion have the shape of wooden penises.

This Festival, still loyal to its origins, celebrates sexual awareness and the prosperity of the whole community donating all the proceeds to HIV research.

Photo credits: flickr.com

Japan Folklore: Miko

Miko (巫女)

"The Shrine Maiden"

Photo credits: pinterest.com

We have seen them in many different anime: Rei Hino, the brave Sailor Mars from Bishōjo senshi Sērā Mūn, the mysterious Kikyō from Inuyasha, or the cheerful Hiiragi twins from Lucky Star.

All these characters shared the same occupation: they were miko, girls that serve as helpers in Shinto temples managing various functions. In fact, we find miko committed to helping the priest in his functions, they keep the temple clean and collect the offerings of worshippers.

Defining this figure by Western standards in very difficult. Miko are not comparable to Christian nun, nor are they actual Priests, even though in Shinto women are allowed to become priests. They are more similar to the oracles of ancient Greece, or to shamans, as in ancient times they were gifted with the possibility to talk with the kami, Shinto deities. By entering a state of trance, they could intercede with the gods and then communicate their will to the humans. These divinatory gifts and their ability to communicate with the world of the spirits were recognized as Divine will.

The origins

Photo credits: dannychoo.com

Their origin dates back to the Jōmon period, the Japanese Prehistory, which goes from around 10,000 BC. up to 300 AD. One of the earliest record of anything resembling the word ‘miko’ can be found in the name of the Shaman queen Himiko (c. 175 - 248). She was the ruler of the Yamatai, the most powerful among the kingdoms in which archaic Japan was divided. But we do not know if Himiko was a miko or not.

The word ‘miko’ is made of the kanji 巫 "shaman, unmarried virgin", and 女 "woman", and it is generally translated as ‘Shrine maiden’. An archaic form of the word is 神子 “Divine child”.

Their strong connection with the deities is also testified by the fact that miko danced the kagura (神楽), literaly "god-entertainment” or “music for the gods". This is an ancient Shinto dance rooted in Japanese folklore that links to the goddess of dawn, Ama-no-Uzume. It is said that with this dance the goddess managed to convince Amaterasu, the goddess of sun, to leave the cave where she was hiding after quarreling with her brother Susanoo, the god of the storm.

The kagura dance was often presented at the imperial court by those miko who were in fact seen as the descendants of Ama-no-Uzume.

In ancient times, miko were considered essential social figures, and this role meant great commitment and responsibility. Their divine bond identified them as messengers of the will of the kami, but not only this. It also placed them in the position to influence the social and political life, and therefore the fate of the village where they served.

However, they underwent a considerable crisis starting mainly from the Kamakura period (1118-1333). In fact, there were attempts to try to take hold of their shamanic practices, and miko, without anymore funds, were forced into a state of mendicancy. Some of them sadly fell into prostitution.

After a period of great transformations during the Edo period, in 1873, the Religious Affairs Department (教部) issued an edict called Miko Kindanrei (巫女禁断令). It prohibited all spiritual practices of young miko.

How to become a miko

Photo credits: thirteensatlas.wordpress.com

The path to become miko was long and difficult. Chosen by the clan on the basis of her spiritual strength, or because she wa a direct descent of a shaman, the girl began her preparation at a young age, usually with the first menstruation. It took three to seven years to become a full-fledged miko.

The girls would wash in cold water, practice abstinence, and perform other purification acts. Everything was aimed at learning how to control their state of trance.

They learned a secret language only known to shamans, and they also needed to learn the names of all the kami relevant to their village. They also learned the divinatory art of fortune-telling and the dances they needed to perform in order to enter the state of trance necessary to talk with the deity.

At the completion of this training there was a ceremony that symbolized the marriage between the miko and the kami she would serve. Dressed in a white robe that represented her previous life, the girl entered a state of trance and was asked which kami would she serve. After that, a rice cake was thrown at her face causing her to faint and she was laid down in a warm bed until she woke up. Then, she would wear a colorful kimono symbolizing her marriage with the deity .

Due to this bond with the deity, young girls had to remain virgin. Still, there were cases of miko with a particularly strong spiritual power that continued their service even after marriage.

Miko today

Photo credits: muza-chan.net

Nowadays the figure of miko still exists but they are mostly young university girls who work part-time at the temple. They assist the kannushi or 'man of god' in the various functions and rites of the temple, perform ceremonial dances, keep the temple clean and sell omikuji, sheets of paper on which is written a divine prediction. They generally do not need any specific preparation and do not necessarily need to be virgins, though they are still required to be unmarried. The kagura dance has become a mere ceremonial dance and it is no longer a way of coming into contact with the divine entity.

Their traditional outfit consists of a white haori representing their pureness, for the upper part of the body, and a pair of red hakama. Red or white are the ribbons in their hair.

During the ceremonies they use bells, sakaki branches, or offer prayers playing a drum. Among other ritual objects there is also the azusa-yumi, a bow that was once used to ward off evil spirits. In the past they also used mirrors to attract the kami and katana.

Maybe miko have lost their divine bond, but they still retain the millenary tradition of taking care of the temple, remaining one the most famous figures of modern Japan.

Photo credits: pinterest.com

Japan Folklore: Hōnen Matsuri

Hōnen Matsuri

Photo Credits: google.it

The Honen Matsuri is celebrated every year on March 15 throughout Japan. The most famous one takes place at the Tagata Jinja, in the small town of Komaki, outside Nagoya, with photos and videos available on the Internet. But in other parts of Japan, such as the Honen Matsuri of Okinawa, this festival is still considered a sacred and secret rite and no photo or recording is allowed. Even speaking or writing about what has been seen is technically prohibited.

Hōnen Matsuri (豊年祭), literally “Harvest Festival”, has a 1500-year-long history: its purpose is to guarantee the fertility of the harvest for the following year. A ritual full of blessings for the harvest, but also for all sorts of prosperity and fertility in general. This celebration could take on obscene features, at least in western eyes, because its symbol is a 280 kg cypress pine phallus, with a length of 2.5 meters. But it is absolutely not like that.

Phallic rites have in fact prehistoric origins. It is believed that this local indigenous rites, and the corresponding vaginal fertility practices and beliefs, were easily accommodated by the new system of Taoist beliefs that were taking root in Japan. System of beliefs that would later form the Way of Yin and Yang, the traditional esoteric cosmology. The local fertility cults co-existed and appear to have been encouraged, institutionalized and presided over by the royal elites from Nara. Élites who established themselves as feudal lords over expanded local areas.

The celebration of fertility

An important element of Japanese Shinto festivals are processions, in which the kami (Shinto divinity) of the local shrine is transported across the city in a mikoshi 神輿 or 御輿 (palanquin, small portable shrine). It is the only time of the year in which the kami leaves its shrine to be carried around the city. It is said that this transporting of the deity rite is based on a legend about the enshrined kami, Takeinazumi-no-mikoto. He had an enormous penis and took a local woman, Aratahime-no-mikoto, as his wife.

At 9:00 am preparations are underway: food stands peep out with their chocolate bananas carved in the shape of a penis and decorated at the base with marshmallows. Here and there, stalls of souvenirs, statuettes and other objects to be offered to the loved ones wishing for great fertility. These statues allow couples to pray for a child, the unmarried pray for a husband or wife, while farmers hope for abundant harvest. Everything enlivened by the unfailing distribution of all-you-can-drink sake contained in big wooden barrels.

Photo credits: thingstodoinnagoyawhenyouredeaddrunk.wordpress.com

The ceremony begins around 10:00 pm. Priests sprinkle the road with salt to purify the way ahead of the carriers. They also say prayers and impart blessings on participants and mikoshi, as well as on the large wooden phallus that has to be carried along the parade route. The starting point is a shrine called Shinmei Sha (on even-numbered years), located on a large hill, or the Kumano-sha shrine (on odd-numbered years), to arrive at the Tagata Jinja shrine. Once here, there is the traditional mochi nage rite: participants fight to grab one of the small rice cakes thrown by the officials from their raised platforms. These sweets will bring good luck for the next year.

Japan Folklore: Tennin

Tennin

Photo credits: google.it

The roots of Buddhism in Japan are very deep and follow the history of the country itself, thus evolving together with it. In fact, Japanese Buddhism largely consists of the continuation or evolution of ancient schools of Chinese Buddhism. Some of these schools, now no longer existing in their country of origin, once introduced into the Japanese archipelago continued to live and change.

Furthermore, through these religious relations, Chinese writing and culture were also introduced in the country representing the base of the proper History of Japan (6th century). Buddhist monks will retain the position of the most important intermediary and interpreters of the continental culture in Japan for a long time.

Celestial Beings

When we refer to Buddhism, we are immediately led to think of Buddha. In reality, there are other very important figures that accompany the Buddha and who live in the Buddhist paradise with him. Among these figures we find the Tennin, that are the result of a long process of assimilation and transformation.

Tennin , whose name is made up of the kanji 天 which means sky and 人 person, are literally "celestial creatures", spiritual beings. They include the HITEN 飛天, Flying Beings, the UCHUU KUYOU BOSATSU 雲中供養菩薩, Bosatsu on Clouds, the TENNYO

天女,Celestial Maidens, the TENNOTSUKAI 天の使い, heavenly messengers, and the KARYŌBINGA 迦陵頻伽, who are Celestial Assistants that appear in many forms but that usually possess the body of a bird and the head of a Bodhisattva.

Photo credits: google.it

They are not specially worshiped, although people do accord them some veneration by placing flowers, water, and rice at their feet. Their function is to protect Buddhist law by serving the DEVA, or else, the TENBU group, that includes other divinely spiritual beings, and creatures like the Dragon, the bird-man Karura, plus Celestial Nymphs and Heavenly Musicians among them.

Most originated in the ancient Vedic traditions of India. The Sanskrit word used to refer to this celestial beings is Apsara, often represented as divine beauties and dancers who populated Lord Indra’s court in Indian mythology. In Japan the Apsaras take the name of TENNIN.

In the arts, they frequently appear as dancers and musicians adorning statues, paintings and temples in China, Japan and Southeast Asia. Their attributes are not clearly specified in Buddhist texts and therefore their appearance is quite varied. In Japan, they are often shown standing or sitting on clouds or flying in the air in graceful poses. They are often shown playing musical instruments or scattering flowers to give praise to the gods, and usually wear light and floating celestial garments, embellished with scarves of gauze, the Tenne.