Japan History: Yamaoka Tesshu

Ono Tetsutaro, better known as Yamaoka Tesshu, was born in Tokyo on June 10, 1836. His father was Ono Asaemon, of the Tokugawa court, and her mother Iso was the daughter of a monk of the Kashima temple. At the age of 9 he began the practice of Jikishinkage ryu and a few years later the Hono ha Itto ryu, while at the age of 17 he started the study of the spear with the master Yamaoka Seizan, who died prematurely two years later. Tetsutaro was adopted into the master's family, and married his sister, taking the name Yamaoka Tesshu.

Yamaoka Tesshu and his history

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: musubi.it

Although he had a not negligible physicality, considering his 185 cm height and his weight of 110 kg, he was able to assert himself only with his incredible personality and sensitivity. However many times he was not able to stop himself, even to the point of denying the existence of Buddha, sentient beings and realization. Nothing to give and nothing to receive.

At that point, Master Dokuon struck him with his pipe and said: "If nothing exists, then where does this anger come from?”

From the world of the sword, he received many teachings. In one of the meetings with master Sasakibara Kenkichi, he stood still for 40 minutes together with his opponent, facing each other in their respective guards until both rested their weapons. At the age of 28, Tesshu was unexpectedly defeated by the 40-year-old Asari Gimei, master of the Nakanishi Ha Itto-ryu school. From that moment on, he could no longer give peace to the idea of defeat against an older man, of whom he had become a disciple but failed to understand his teaching. Asari, without hitting him, forced him to step back out of the dojo by closing the door in his face.

Tesshu's introspective study lasted 16 years, without being able to understand what was wrong with his technique, his lifestyle, despite the training and Zen teachings. On March 30, 1880, Tesshu during a zazen session went to Asari and asked him for a new fight. Asari declined, justifying himself with these few words, "Now you have arrived". From that moment he left teaching and his school to Tesshu who succeeded in developing a method called Muto ryu (school without sword) different from the Itto ryu especially in teaching, still practised but by a very small group of people. He died on July 19, 1888, at fifty-three years of age due to stomach cancer. Before dying, he wrote his Jisei no ku (poem of death), closed his eyes and, even in death, did not abandon his style assuming the formal posture of zazen, as can be seen from the drawing of his disciple Tanaka Seiji.

During Tesshu's funeral at the Zensho-an temple the monk Tekisui composed these verses:

Sword and brush balanced between Absolute and Relative

His loyal courage and noble strength pierced Paradise.

A dream of fifty-three years,

Wrapped by the pure fragrance of the flourishing lotus in the middle of the roaring fire.

Again, Katsu Kaishu, a great swordmaster, wrote the following words next to a portrait of Tesshu:

Valiant and wise, this virile man accomplishes great things

His sword was incomparably sublime

Its illumination embraced everything

Will future generations ever see the same?

Explanation of Mute Ryu

photo credits: wikipedia.org

The goal of Muto Ryu is "no enemy". Everything depends on the mind. If we imagine a very skilful opponent, our sword stays still, if we imagine a weak opponent, the mind opens and the sword is free. This is proof that nothing exists except the mind. Taken by agitation, a warrior would move the sword without thinking and confusedly without hitting the opponent. From this idea was born the school of non-sword (Muto ryu). Out of mind there is no sword, this means: not sword corresponds to not mind; not mind means a mind that is stable everywhere. If the mind stops, the opponent appears; if the mind keeps moving there is no enemy. Continuous and intense training leads to the stage of no enemy.

Tesshu's method required intensive and incessant training focused mainly on basic principles. The first 3 years were dedicated to the study of the 5 basic kata of Muto ryu and it was forbidden to follow in that period the teachings of other schools. Three levels of seigan were foreseen for advanced students, who were admitted only after having passed a trial period consisting of 1000 consecutive days of training. In order to pass the first seigan level, 200 sword fights had to be fought in a single day; the second level provided for 3 days with 600 fights and the third, 7 days with 1400 fights.

The name of Yamaoka Tesshu's dojo, Shumpukan, comes from a poem by Chinese monk Bukko Kokushi:

In heaven and on earth there are no points to hide

Joy belongs to those who recognize that things

They are empty and man is also nothing.

Splendid indeed the long Mongolian swords

Blasting the spring wind like a flash of light

The shumpu, the spring wind, gave the name to the dojo.

The writings of Yamaoka Tesshu

Below we have some writings by Tesshu that better describe his strong personality:

Return to the Beginner's Mind, August 1882

If the wonders of swordplay elude you, it returns to the beginner's mind. The beginner's mind is not just any kind of mentality: striking as the only intention without thinking about the movement of the body and moving forward with force is proof that you have forgotten yourself. Technicians are hindered by analytical thoughts. When the obstacle of a discursive approach is overcome, the wonders of the art of the sword can be appreciated. In the beginning, it is necessary to practice with well-tempered swordsmen in order to discern one's own inadequacies. Pursue your study to the end, awaken your irresistible strength, practice tirelessly until your heart is immovable, and then you will understand. Practice until no doubt remains. Surely the time will come to discover the wonders.

From Itto shoden Muto Ryu Kanaji Mokuroku: Suigetsu (the moon in the water), April 10, 1884.

Even when the water from a puddle is moved in the ladle, the moon is reflected in it. The moon's reflection is not lost when the water moves from ladle to ladle. When you are disturbed, then there is no reconnaissance; the moon does not appear in the agitated water. If your mind is calm and the ladle is still, the moon's reflection is maintained.

Do not concentrate

When hitting your opponent

Move naturally

Like moonbeams penetrating

In a homeless hut

You may be unhappy with a roofless hut, but the same moon that illuminates the skies naturally fills it with its light. So, you can attack your opponent and win. Regardless of keeping your little self, charge towards your opponent. If you are confused or nervous you will surely lose.

Other Famous Phrases

As a samurai, I must strengthen my character; as a human being I must perfect my spirit

Thirst for victory leads to defeat; not tiring of defeat leads to victory.

If you want to obtain the secrets of such wonderful techniques, drill yourself, harden yourself, undergo severe training, abandoned body and mind; follow this course for years and you will naturally reach the most profound levels. To know if the water is hot or cold you must taste it yourself.

Zen is like soap. First, you wash with it, and then you wash off the soap.

Do not think that this is all there is. More and more wonderful teachings exist.

The world is wide, full of happenings. Keep this in mind and never believe 'I'm the only one who knows.'

The moon does not think to be reflected, nor does the water think to reflect, in the Hirosawa Pond.

Unfortunately, many of his writings are apocryphal, but that does not make them less profound and important for life than anyone who has read them. We think that they can be a help even nowadays in many situations.

Political and Social Life

photo credits: wiki.samurai-archives.com

Tesshu also had an active political and social life as a negotiator. He was first in the service of the shogun, so at the end of the war Boshin in 1869 treated the surrender in front of the siege of the imperial forces commanded by Saigo Takamori.

His success was the fact that he focused on establishing contact with the enemy forces, with linear but provocative conduct: he intimidated the enemy of the emperor to let him pass without fear.

If we think of Tesshu's impetuous character, never willing to give in to compromises, it is really strange to see him as a great negotiator. In his short and adventurous life he was also the emperor's bodyguard, with his readiness of reflexes and decisions.

Wabi-Sabi, introduction and detailed focus

What is Wabi-Sabi and why is it so fundamental for the Japanese? Accepting the natural cycle of growth and decay of reality. To grasp its meaning, its beauty. To live life as it is, without wanting to change its colours, and yet to fulfil your sense of life to the best of your potential. Japanese sensitivity and psychology could be traced back to these two elusive words alone.

Wabi-Sabi 侘寂 The most ineffable experience in the design of Imperfection

Guest Author: Flavia

In the world is often associated with design, but Wabi-Sabi is much more than that. Its origins are linked to those of the Tea Ceremony, therefore, the matrix once again is Zen.

It is actually an experience, translated into a worldview as well as a refined aesthetic sensibility, which would manifest itself when the highest form of something is achieved. A mix of emotions and feelings emerging from a state - an instant - of awareness that allows us to grasp the true nature of life's lights and shadows. So when we speak of beauty from now on, it will be understood in a broad sense, not only as aesthetic beauty in the strict sense. Also because, it is an aesthetic consciousness that encompasses the outward appearance, but also transcends it.

It must be said immediately that, since it is a metaphysical concept that we have in our hands, any attempt to frame it in words once and for all will always be risky. Therefore, the best way to know it remains to experience it directly. The fathers of Wabi-Sabi themselves - immediately realizing that a cognitive approach would not be the most appropriate - used images or allegories to try to render the idea. Even the modern Japanese, when questioned about the definition, tend not to throw themselves into verbal transpositions without the slightest moment of doubt. Or, each one, gives a different explanation according to his own sensibility.

It is with this awareness, then, that today we propose to explore with you this concept as mysterious as ineffable.

photo credits: reddit.com

Imperfection, Impermanence and Incompleteness

It is the trinomial par excellence to which the Wabi-Sabi aesthetic is irremediably conducted and synthesized. It refers to the Buddhist vision of life, whereby the beauty of things does not lie in the absence of defects or in eternity - which is not of this world - but in their imperfect and ephemeral intrinsic characteristics.

However, there seems to be something more in what Wabi-Sabi seems to reveal: Imperfection, Impermanence and Incompleteness would be a point of departure rather than a point of arrival. They would be the basis to keep in mind, in our co-creation with reality, rather than the summit of the mountain to be reached. In other words, it would suggest to recognize reality as it is, to be realistic: not to insist on forcing it to be something that cannot be, that is, perfect. But at the same time it would suggest - and that's the beauty of it - to do everything necessary to accomplish your task or role, given this base of imperfection, in the best possible way. Similar to what happens in Chadō, but on this, we will come back later.

Personally, I find that Impermanence and Incompleteness are also "sub-sets" of the mother concept of Imperfection. What else denote the impermanence and incompleteness of something if not its imperfection? Similar speech for the concepts of defect and beauty. They are different but they are also the same thing: the "ugly" can be referable to the size of the defect, ergo of the imperfection (which makes it beautiful). I believe that keeping this in mind helps to approach the Beauty discourse at 360°. Since Wabi-Sabi could refer as much to a work of art as to a situation or even a map.

Now, however, the time has come to finally get to know the terms Wabi and Sabi.

Wabi (侘) - Beauty and tranquillity in essentiality

Indicates a taste for simplicity and tranquility. From the linguistic point of view the Kanji - ideogram -「侘」è composed of the radical 「⺅」di person + 「宅」di home. Almost as if to visually indicate a person who, alone, is leaning against his little house. I use the verb "leaning" because that little man so placed inside a Kanji can be explained as if the little person was leaning against what is represented. Well, as we will see shortly, the original meaning of Wabi 侘 was one of loneliness.

The beauty promoted by Wabi is discreet by virtue of the presence of imperfections generated in a natural, spontaneous (never intentional!) way. Natural defects are the essential value of the object, the person or the situation. It makes them perfect ... and consequently, beautiful. A rustic or not ostentatious beauty that prefers the natural instead of the artificial.

Natural defects find space where functionality - and not form as an end in itself - is the main criterion of life. In other words, in simplicity. On the contrary, in sumptuousness or complicity defects are invariably suppressed: beauty thus becomes an end in itself. The exasperated complicity then, tends to accumulate concepts, thoughts, forms etc., weighing down with complex tangles what could be essential and therefore even more functional. For these reasons, Wabi seems more oriented towards Incompleteness and Imperfection.

photo credits: youtube.com

Sabi (寂) - Beauty and quietness in the advance of time

The Kanji Sabi「寂」è given by the union of the radical tetto「宀」con kanji「叔」che may mean uncle or old or mature man. The suggested image is therefore that of a person in the final stage of his life under a roof. Going through the various meanings, the concept in the background refers in any case to an idea of decline or deterioration. The meaning of Sabi寂 is still today that of loneliness, desolation, calmness, maturity (think that the adjective 寂しい "Sabishii" means to be or feel lonely). And although they are written with different Kanji, the root of the Japanese words of "rust", "rusting" or "deteriorating" is pronounced by chance "Sabi".

Well, the beauty promoted by Sabi has to do with the passing of time. It enhances the intrinsic qualities of things and people that originated as a result of the effect of time on them (deterioration/aging but also experiences). Because it is only thanks to time that these qualities have been able to emerge in that particular way.

Then there is a message in the "wear and tear damage" that if we are able to grasp it, especially in time, it is of enormous value: that of reminding us that nothing, from objects to situations, is forever. And that therefore it is necessary not to "chinchishize" and seize that precious moment in which we can appreciate them because they are still here with us: now.

This is why Sabi seems more oriented towards Impermanence and Imperfection.

Wabi-Sabi, self example

But it was not always so. There was a time when such awareness was not yet there. Originally, in fact, the moods associated with Wabi and Sabi were quite low:

- Wabi, as anticipated, indicated a sense of loneliness; one to be on one's own associated with nature, in the style of hermit isolation.

- Sabi, for its part, denotes a sense of coldness or aridity, poverty, restriction, decay.

They had in common this dimension of loneliness and desolation... and the sense of melancholy for not being able to enjoy the company of their fellow men.

In short, they had their own low notes.

Usually, however, it is from the lowest notes that the best (re)births take place. And this is what has happened. With the advent of Zen Buddhism the general consciousness undergoes a metamorphosis and so around the fourteenth century the connotation of the two concepts is reversed.

- Wabi: isolation in nature is now seen in all its value and "rustic simplicity" revalued. Thus takes shape the pleasure for the quiet and simple life.

- Sabi: it evolves in the beauty of Impermanence that is the added value and serenity that things and people achieve with wear and aging.

Bitterness is now softened by mixing with it a sense of calm. The melancholy - given by an existential condition felt as miserable - thus turns into a bitter-sweet feeling that some have tried to define "serene melancholy" or "sad beauty". In some ways it might, at times, remind one of the Portuguese/Brazilian Saudade (also difficult to transpose verbally). But what it most strongly recalls is the previous Mono no aware (物の哀れ), another key concept of Japanese aesthetics.

Summing up: in their early days Wabi and Sabi represent nothing more than their shadow side. A dark version of themselves that "exorcised" from Zen, is born to new life. Abandoning forever the darkness in which they were born, illuminating themselves in those characteristics previously corroded by darkness.

The divine, essence of nature

The sense of austere and quiet beauty that Wabi and Sabi together transmit could only originate in the spiritual isolation of Zen Buddhism. Only in a state of mental and therefore spiritual stillness is it possible to observe joy and sadness alternating exactly like the cycles of nature and seasons. Joy for what has been or what will be, sadness for what has made its time or what is to come.

The only thing that always remains the same is stillness. A stillness given perhaps by this very certainty about the cyclical nature of things. Their coming to an end may generate some melancholy, but at the same time it gives us confidence, because we know that the time will come for a new rebirth, a new beginning. For this reason, nature is also a teacher of patience. Every end presupposes a new beginning, nothing really dies. In the present moment, however, the only thing we know is what is manifest in this moment, inside and outside of us.

Serenity and confidence in becoming, awareness and attention to what we see unfolding in the present moment: these, the only certainties of the human being present to himself.

If there is stillness there can be no fear. Serenity and fear are mutually exclusive. If fear manages to make its way, it means that, at least in that present moment, there is no state of inner stillness. To be able to understand all this, and perhaps to experience Wabi-Sabi, even a single moment of waking would be enough.

photo credits: 4travel.jp

«Kata–Katachi»: as diligent as nature

To accept the natural becoming, to let it flow, does not mean to become passive, to let oneself go to "disorder". The diligent execution of the gestures of the Tea Ceremony, in which Wabi-Sabi has its roots, shows us just that. As we said in the article dedicated to it, the principle of kata-katachi - common to all Japanese disciplines - aims at achieving harmony with oneself and the surrounding world. How? Through a constant, diligent repetition of certain gestures aimed at making these same gestures our own, to make them come natural to us.

This is the essential Japanese logic: observe-apply, simply; but apply diligently. And this is a bit what happens with the observation of nature itself. Observing the behavior of nature and replicating it could be said to be the very first great application of this principle by the Japanese people.

This suggests us, as we said at the beginning, that it would not be enough to stop to accept the Imperfection: but that everything should fulfill its task or function within the design of the Imperfection. For human beings, it is a matter of acting in their roles by completing everything in the highest possible version. In essence, giving the best of oneself.

And if in all this some "defect" wants to manifest itself, at that point, to welcome it, just because you have already done your part. Seize then the beauty of that defect, in truth so perfect in its imperfection, so complete in its incompleteness, just for having emerged in that way.

In this way we would be more like nature...dancing with it at its own pace. It is in such a frame that Wabi-Sabi could come. I could be wrong, but it would seem to be a moment between one cycle and another, an instant of silence between the cycle at the end and the next. An empty space where both times do not exist but, at the same time, are connected. As if it were a very thin, invisible thread, visible only at that juncture. It is in that moment of stasis, where the boundaries between outside and inside are missing, that Wabi-Sabi could manifest itself.

photo credits: Film The Last Samurai

Imperfection as a "touch of the divine"

The perception of Wabi Sabi would therefore seem to emerge where a degree of awareness has been reached such that there is a detachment from the idea of absolute perfection. One understands the sense of imperfection and transience of things and one can grasp its spontaneous and genuine beauty. You welcome it as an added value - divine touch - to your creation: it is a balanced beauty.

Knowing how to recognize that Imperfection is the touch of the divine implies understanding when it is time to let go of your "brush". It is necessary to know how to let go when everything that had to be done has been completed and the feasible moves all exhausted. To get caught where our task is finished or to try to intervene on the "touch of the divine" - not recognizing it as such - is certainly a point where Wabi Sabi cannot emerge. Because it lacks its basic fertile ground: tranquillity.

photo credits: youtube.com

Wabi-Sabi, the origins: the Buddhist vision

The principle that is the premise of the Wabi Sabi experience is to be found in the Buddhist philosophy of the Three Signs of Existence, so everything that manifests itself in this reality is subject to three characteristics:

● Impermanence

Everything that is, outside and inside us, is destined sooner or later to leave room for something new. It is a constant cyclical becoming in which everything that has a beginning also has an end. Moreover, the very existence of matter is regulated by duality: everything necessarily manifests its opposite. This is because the One, in matter, must necessarily split into two parts. If an element of a binomial (beginning-end, light-dark, positive-negative, male-female, birth-death...) is missing, imbalance is generated... because they are two aspects of the same thing. You may like it or not, but that's how matter works. Therefore - as long as you are in it - it is not possible to escape such laws.

● Insubstantiality

Nothing is random: each event derives from the concatenation of n factors even very far away in time and space. Therefore nothing exists, in itself, as a manifestation independent of what originated it. There is therefore a link between all the things of the world, so apparently disconnected from each other, including our human Self. By participating in the changing nature of reality it can only be fragile, incomplete: therefore, much emphasis is placed on disidentification from that part of oneself. The unharmonized Ego tends to draw sap from material reality alone, making us remain trapped in the temporal illusion of past and future. Thus also allowing other types of illusion to make their way. That is why the present moment, the attention to the here and now, is essential.

● Suffering

Nothing in the world will ever generate lasting satisfaction. At the very moment when there is happiness, its end is inevitably written in it (it is the law of polarity). And in fact, the true existential goal to be set is Serenity, not happiness. Only Serenity can guarantee constant well-being, even in dark moments, because it is born of Presence. Happiness, as beautiful as it is, is nevertheless the child of emotions. Therefore, of duality.

Accepting this vision of things allows for greater realism. Become aware of how things are, accept, adapt and thus understand how to move in reality. Develop a healthy, lucid, vision of the reality around us is essential to move in this world.

photo credits: youtube.com

Zen philosophy, fertile ground for Wabi-Sabi

Eliminating the root of suffering is therefore possible: the key lies in adapting to the nature of reality as it is. Suffering originates precisely from a denial of reality: from resistance, from attachment. That is, from control, dictated by fear, which does not allow things to flow. But what gives rise to this fear? Probably, from the mistaken belief that imperfection somehow leads us to existential ruin. As if every time, we risk to die.

Instead it makes no sense to resist something that is bigger than us, on the contrary it gets worse. It is to want to sail against the current. Such is the physiological nature of the reality that surrounds us: isn't it better to "make friends" and find a way to collaborate?

Here then are the "tips" of Zen philosophy for a more balanced and serene life:

● Perfection does not mean absence of defect

The imperfection of something does not qualify it as negative. The perception of what is "defect" or "ugly" is also relative. It varies from civilization to civilization, from person to person...even within the same person. And if by hypothesis they were fixed law, there would still be a precise reason for being, wouldn't there? In order to internalize this vision, however, it is essential to acquire an important state of mind: non-judgment.

● Accept Transience and Imperfection

Why reject something that is a structural part of the reality in which we live? That's just the way it is. It is wiser to accept what is not in our power. And still keep an open heart! Because the same Impermanence, which we fear so much, often reserves us pleasant surprises and opportunities.

● Remove all that is not needed

To free oneself from unnecessarily necessary things in favor of a more direct and deeper contact with the things of our life, starting from the most "insignificant". Their essence, their meaning, their beauty...become so perceptible. To relieve ourselves from the useless superstructures with which we often tend to weigh everything down and which distract us from simplicity - which alone would be enough to make things flow even more efficiently.

● Live the present, detached from the result.

There is no such thing as the perfect moment. Chasing an objective at an imaginary point in the future is a trap: the future, in itself, simply does not exist. The "never having enough" signals the onset of the second trap. You become the so-called hamster in the wheel. This doesn't mean that you don't have to have goals: it simply means to set the right goals but, let them go, without obsessively staring at them, losing sight of the present.

How Wabi-Sabi is rooted in the Japanese spirit

However, we can't leave ourselves, given our common origin with Wabi-Sabi, without remembering Chadō. Previously we have already had the opportunity to enter the Tea Way. In our dedicated article we have seen how the Tea Ceremony has gradually evolved from the more opulent form Shoin to Wabi-cha (Cha 茶 means tea). At the head of this "Wabi-cha", a direct line of Zen masters. Murata Jukō and Sen no Rikyū in particular, are still considered the fathers of Cha no Yu. In addition to them there will be another character to anchor the Wabi-Sabi in another important area of the Japanese cultural scene.

Here then is a snapshot of the historical evolution of Wabi-Sabi:

● XII century

It all begins with Myōan Eisai, a Buddhist monk from the tent school. Eisai is the one who brings from China the Zen doctrine (Rinzai) and with it the use of tea, thus paving the way for the development process of the Tea Ceremony.

● XIV century

The terms Wabi and Sabi undergo that semantic metamorphosis of which we spoke at the beginning. Their meaning begins to overlap and they gradually begin to use them together. For example, they will notice the rustic objects that will increasingly take the place of the luxurious Chinese objects typical of the initial Shoin-cha.

● XV century

Murata Jukō makes his appearance. With the approval of the Shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa, he manages to introduce the Wabi style in the practice of tea that spreads in the country. Jukō acts for example by reducing the number of utensils of the ritual, thus bringing more attention to them (remember, take away what is necessary).

● XVI century

It is the turn of Takeno Jōō, a student of Jukō, who instead focuses on the simplification of the tea ritual environments. For example, he introduces more modest materials such as clay, bamboo and removes wood from some parts. In antithesis to the Shoin style, he also brings the use of indigenous objects on a par with those of Chinese origin.

The student of Jōōō, Sen no Rikyū, the most revolutionary of all, will complete the work by codifying the Ceremony once and for all.

● XVII century

Matsuo Bashō, the greatest Japanese poet, will transpose Wabi-Sabi into poetry. During his long wander in solitude in the nature of Japan he will succeed, just like a painter with his canvas, to capture its images. The success of his Haiku compositions, so essential, silent and empty, lies in having used words to paint the situations and landscapes he encountered rather than describe them.

photo credits: angelotrapani.wordpress.com, allpainters.org

Balance is the matrix of everything

At the end of our journey through the "landscapes" of Wabi-Sabi we have understood that the underlying condition of everything is inner peace. We must be silent inside ourselves and silence everything that makes noise inside us. In other words, we need to (re)establish balance. Order, balance...if you pay attention to it, you always go back there. Too much of anything generates imbalance.

The secret to make friends this reality resides instead in learning to move in duality, in knowing how to govern the extremes.

We have also understood that letting reality flow includes our range of action. For us too, just like nature, to fulfill our function in the highest form of expression possible. Instead, we should not be confused with a passive letting ourselves be overwhelmed by events which, on the contrary, is an imbalance in everything and for everything.

Passiveness and control, two sides of the same coin.

The error of us Westerners, for example, more than in our idea of beauty per se, lies in our negative approach to Defect. We have always culturally recognized beauty in flawless perfection. Which, in itself, is not wrong: it indicates that we have well understood the metaphysical nature of the divine which, as such, has no defects.

However, we have not calculated one thing: that "original" perfection is not of this world! And so, in our search for the meaning of life, we try at all costs to bring that kind of perfection here. Not understanding, that this part of the Universe is designed to be imperfect. And that the divine, in these parts, also manifests itself through the defect (indeed, often the Imperfection is the most direct manifestation of it). Our misunderstanding is all there.

Imperfect means simply imperfect. We abandon judgment because it precludes us from seeing a whole spectrum of possibilities, making us remain confined in a narrow slice of reality.

Defective, 100% Western friends, does not mean absolute evil: let's drop this illusion. If evil can be spoken of, then this should rather be sought in the imbalance. For it is imbalance that prevents us from being quiet, lucid and present to ourselves.

And it is only in quietness that, when we least expect it, in a moment of emptiness we can suddenly find ourselves, from the divine point of view. From there, "from above", magically, we will be able to see the dance of duality and there our human nature will return melancholy to remind us how, for the moment, we are part of that dance.

photo credits: wakuwakumedia.com

Introduction to Japanese poetry

Italy, France, England, America and many other countries in the world offer a vast poetic production, but what is Japanese poetry like? Here we are on this fascinating literary journey to discover something more about the Land of the Rising Sun!

photo credits: grangerprints.printstoreonline.com

Introduction to Japanese poetry

Author: Sara | Inspiration: Tokyo Weekender

Japanese Poetry: Kanishi

photo credits: wikimedia.org

Curiously, most of the literary works of Japanese poetry were born during the Tang Dynasty, from the encounter of Japanese poets with Chinese ones. And so, under Chinese influence, Kanshi 漢詩 became the most popular form of poetry during the early Heian period among Japanese aristocrats and became increasingly popular in the modern period, especially among academics and intellectuals. The themes were free, while the forms were more rigid: the classical ones counted about 5 or 7 syllables in 4 or 8 lines, following the rules of Lushi 律詩 (rhyme on even lines with a regulated tone) and jueju 絕句 (rhyme in even lines and composed only of quatrains) based mainly on the tone of Mandarin Chinese.

The major exponents of this style are certainly Kukai, Sugawara no Michizane, Maresuke Nogi and Natsume Soseki.

Waka

photo credits: https://matcha-jp.com/jp/289

Unlike Kanshi, Waka 和歌 was classical poetry written in Japanese with two very precise forms: Choka, 長歌, or long poems with no length restrictions. The structure is simple and consists of 2 lines of 5 or 7 syllabic sounds (which determine the accent) that ends with 3 lines of 5, 7 and again 7 syllabic sounds. Tanka, 短歌, instead has a similar structure, but they are shorter poems, often consisting of only five groups of words respectively of 5, 7, 5, 7 and, finally, 7 syllabic sounds. Waka does not follow the rhyming rules and is still very popular in modern Japan, even if now the Tanka form is preferred: the more incisive brevity reflects as always the essentiality of deep culture. The poet par excellence is certainly Machi Tawara.

Haiku

photo credits: wikimedia.org

What is the Japanese poetic composition that we consider among the most famous? Without a shadow of a doubt, it's the Haiku, 俳句. Loved by all, it is usually composed of 3 verses and 17 total syllabic sounds, schematically 5/7/5. Haiku experienced its development in the Edo period when many poets relied on this genre to describe nature and human events directly related to it. In fact, these small "compositions of the soul" express the beauty of every single instant, representing "the moment" and giving the reader that sense of "enlightenment" thanks to the images that the words evoke. The most famous and beloved poets are undoubtedly Basho, Yosa Buson, Kobayashi Issa, and Masaoka Shiki.

Our journey into Japanese poetry ends here, for now. This is a very short overview that has allowed us to enter the world of literature of our beloved Japan. What is your favourite form of poetry among the above? Mine is easy to guess: I particularly love Haiku. Here is one of my favourites by Matsuo Basho:

Let's take

the marshy path

to get to the clouds.

Continue to follow us to discover other little pearls of this oriental world and I recommend that you continue on the path you have taken: happiness is always in front of you!

Genji's Tale

Murasaki Shikibu is the name behind the Japanese woman who wrote what is called the world's first novel, The Genji monogatari (源氏物語 lett. "The Genji Tale").

Genji's Tale, The World's First Novel

Author: SaiKaiAngel | Source: Tokyo Weekender

photo credits: tokyoweekender.com

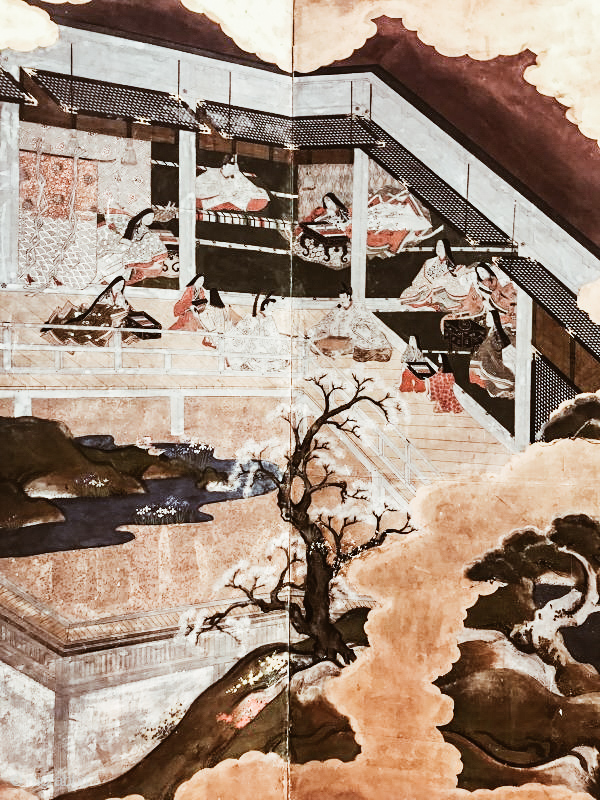

Every work of contemporary art is the result of centuries of cultural history. In the case of Japanese literature, we are talking about 1,000 years of written prose and poetry. It all began in the Heian period (794-1185) with Murasaki Shikibu, a companion and member of a minor branch of the powerful Fujiwara clan. Murasaki was the author of one of the most important literary works in the world, The Tale of Genji, published in the early 11th century. By way of comparison, it is thought that the first novel in modern European history is Cervantes' Don Quixote, first published in 1605.

Heian aristocracy

While Shikibu was undoubtedly a pioneer of fiction in Japan, not much is known about her, not even her first name. At that time, the maiden names of elite women were not registered. The name Murasaki Shikibu would have been created based on one of the characters in The Tale of Genji and on his father's status (Shikibu, which means "Ministry of Ceremonies" in Japanese), although historians still dispute this theory.

Like many women of her status, she lived relatively comfortably, although the aristocratic lifestyle had some restrictions. The elite of the Heian period favoured high education and culture, and often the most powerful individuals were also the most educated.

Men learned everything from poetry and languages to law and politics. Women, on the other hand, were limited to the arts because this was what was considered attractive at the time. Chinese was an important language to know for those directly involved with the court and to participate in literary circles, but women usually could not study it.

photo credits: wikipedia.org

This has not prevented aristocratic women from investing in the creative field, using hiragana and contributing significantly to the genre of the poetic diary. Lady Murasaki's Diary together with Sei Shonagon's The Pillow Book are the main representatives of the genre to date.

Through fragments of Shikibu's diary and narrative work, historians have been able to learn about the unique aristocracy of classical Japan. At the time, poetry and prose were written based on the lives of their authors, but Shikibu's was distinct from the masses in that it was clearly a work of fiction - although many claim that the stories in The Tale of Genji were inspired by real events.

Genji's Tale

Genji's Tale is thought to be the world's first written work of fiction. It’s not certain whether Shikibu wrote the complex story in a couple of years or decades, but what is certain is that this complete literary work is a portrait of the Heian aristocracy in all its complicated hierarchies.

What is even more impressive is that, despite the long list of characters and appearances throughout the book, the story still surrounds only what at the time was less than 1% of the population, the highest elite.

Reading the chapters gives you a vivid idea of what it was like to be a man or a woman in the Heian period, with the corresponding expectations. The protagonist, Genji, is the archetype of a hero of the period, the perfect man. Son of an ancient emperor, his right to the throne was taken away from him and he was demoted to populan when he changed his name to Morimoto.

The Story of Genji Monogatari

The work tells of one of the sons of the Japanese emperor of the Heian era, known by the name of Genji or rather Hikaru Genji (Genji Splendente). Genji, however, is just a different way to read the kanji of the Minamoto clan (the reading On of Minamoto is in fact 源 Gen, the same kanji present in the word Genji), a family that really existed and to which the author wanted to allude. Born from the emperor's relationship with one of his concubines, and therefore unable to be part of the main branch of the imperial family or aspire to the throne, Genji is adopted by the court which allows him to climb the high ranks starting from the position of simple court official.

The whole story then revolves around Genji's love life and his various relationships, thus showing the customs of the court society of the time. Despite his numerous relationships and the different wives he will have during his life, as a libertine Genji still shows his particular loyalty and bond with all the women in his life by not abandoning any of his wives or concubines, especially at a time when for a concubine or wife to be left by her protector meant abandonment of society and marginalization.

Among them, however, one woman was a particular presence in the life of the young Genji: Fujitsubo. The premature death of his mother left in Genji a void that the young man tried to fill throughout his life, always looking for a mother figure in all the women with whom the young man fell in love. He thought he would find the mother figure in Fujitsubo, a concubine of the Emperor, his father.

In the woman, Genji saw not only the sweetness of the mother but also beauty and gentleness, and although he was reciprocated by the woman, the two were forced to repress their feelings because she "belonged", as concubine and then bride, to the Emperor, and Genji had recently joined the Emperor in marriage with Princess Aoi.

The story continued telling the intertwined stories of all the characters whose lives were intertwined and united until the end of the novel, with the conclusion that saw Genji in old age, reflecting in solitude on the meaning of life and the transience of things and their fleeting beauty. However, there are other chapters, known as Uji's Chapters, which, like the rest of the work, continue to recount events even after Genji's death and have as their protagonists Genji's son and a friend struggling with their love affairs.

However, the story ends abruptly, almost in the middle, leaving the various foreign scholars and authors who have translated the English version to imagine that the work has not been completed by the author. In fact, it seems that Murasaki didn't plan any end for the novel but simply continued to write it as long as he wanted or could leave it incomplete.

Structure of the Genji Monogatari

photo credits: rugrabbit.com

The story that tells the life of Prince Genji, tells about the young prince's youth, his rise to success, his worldliness and loves until his fall and then rise again. A plot in which there are bewitching and beautiful female figures as a frame. As for the language, it is very complex and not easy for modern readers: being from the Heian period and moreover in a court environment, Murasaki's language has a very complex grammar.

Each character is almost never called by name but by their honorary title or according to their class. For women, instead, typical colour of their clothing is indicated, different for each female character, or alludes to a woman using the rank of a male relative of the first order to which she belongs.

Another difficulty of the novel is the presence of poetry and conversations written in verse. This often served the characters to communicate subtle and veiled allusions in a court environment: poetry is classic Tanka poetry. Like most writings of the Heian period, the Genji was most likely written all, or almost all, in kana, and not using Chinese characters as it is written by a woman for a female audience.

It is well known that in the Heian era writing in Chinese characters was something purely masculine, but women were forbidden.

Besides many suggestions of a society dominated by men, the novel was proof of something that could be even more crucial: women had undeniably played a great role in the propagation of the arts. In fact, while the Heian period saw many failed attempts to revolutionize Japanese government policies, what's left is a rich attachment to the culture that Japanese society still clings to today.

The prose and poems written in hiragana by the women of the court ensured that the lower classes could also enjoy them. In other words, the Heian period is seen as a time when the art world in Japan was born. Not only Shibiku is an important historical figure for its legacy in Eastern and international literature, but she is a symbol of an era in Japan when women were successful in ways never seen before.

Murasaki Shikibu in popular culture

Shikibu is one of the most significant historical figures in East Asian cultural history and, over the next millennia, has remained a staple in Japanese high schools and colleges, just like Shakespeare in Europe and North America.

There have been many important translations and interpretations, as well as a fair amount of criticism. In Japan, Genji's tale is commemorated on the rare 2,000 yen note and Murasaki Shikibu is the name of the Japanese berry plant.

Like the story of the 47 ronin, Genji's Tale has been adapted for the big screen several times, and the latest is the feature film Genji monogatari: Sennen no nazo (2011). In recent years, Murasaki Shikibu herself has appeared in mobile games such as Fate/Grand Order and Monster Strike, where the characters are inspired by her work.

Shinrin-yoku, forest bathing

The Shinrin-yoku so loved by the Japanese is what we call "forest bathing" and can be healing and regenerating. This practice, whose major exponent is Dr. Qing Li of the Nippon Medical School in Tokyo, is also becoming very famous here in the West. But let's see in detail what it is.

Shinrin-yoku, the forest bathing loved by the Japanese

Author: Erika | Source: Tokyo Weekender

One of the world's biggest health trends at the top of the charts, the Shinrin-yoku has become internationally renowned. However, its diffusion dates back to the late 1980s in Japan. In fact, Forest Bathing has for years been considered a true practice of preventive medicine in the land of the Rising Sun. In support of this, there are numbers of researches conducted around the world that have shown how to spend regular periods of time immersed in the quiet of the woods helps to strengthen the immune defences and prevent diseases But what exactly is this about?

What is Shinrin-yoku, Forest Bathing?

Literally, Shinrin-yoku (森林浴) combines the kanji of "forest" and "bath", and is commonly translated as "bath in the forest". Promoted some forty years ago by the Japanese government, Shinrin-yoku consists of walking in the woods and applying special breathing techniques. However, forest bathing activities are not limited to breathing. In fact, whether you stay active or simply decide to take some time to relax in the forest area, this also brings you back to this practice.

First used in 1982, this term was promoted by the Japanese Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries to encourage healthy lifestyles and protect the nation's beautiful natural ambients. Since 1986, the Forsetale Agency together with the Green Civilization Society has indicated more than 100 areas throughout Japan where this concept of bathing is possible. Even today, there are various techniques to keep healthy, but forest bathing is one of those concepts that goes well with Japanese ideology.

In the early 2000s, several universities and research centres conducted experiments to find out how effective this practice was. The various studies were unanimously positive. In fact, it has been shown how spending time between trees reduces stress, improves mood, lowers pulse rate and blood pressure. But not only that, it also increases concentration and creativity as well as strengthening our immune system.

Perhaps sensitivity, and in particular deeply spiritual and historical respect for the natural world, has made this practice thrive in this nation.

Forest Bathing becomes international

Following the strong success achieved in Japan (about 5 million people practice Shinrin-yoku in the country alone), forest bathing has also become very popular internationally. Today, in fact, it has many followers also in the West, the Duchess of Cambridge herself is a fan, as reported by The Guardian. In this regard, in England, many institutions are promoting this practice as a way to relieve daily stress.

One of the leading figures on the subject, Quing Li, president of the Society of Forest Medicine in Japan and author of the book Shinrin-Yoku: The Art and Science of Forest Bathing, commented:

"Shirin-yoku is for all intents and purposes a preventive medicine. People spend most of their lives indoors. In the case of the Japanese it is 80% of the time, and in the case of the Americans it is as much as 90%. But man is made to live outdoors. We are designed to be connected to the world of nature".

You have to try the Shinrin-yoku

Forest bathing is an easy and inexpensive activity. In fact, it can be done at any time, whatever the weather conditions and does not require special equipment or physical fitness. You can build your experience to measure and according to your needs.

In Japan, the Forest Therapy Society is a non-profit organization that identifies areas with forests and pedestrian roads that have been scientifically evaluated. Here you will find a certified "forest bathing effect". Currently, 62 areas have been certified in Japan, each of which offers "forest therapy roads" with wide access paths suitable for quiet walks, some of which are also wheelchair accessible.

In Italy, we find several destinations equipped for forest bathing, first and foremost Trentino Alto Adige. In fact, on the Renon plateau and in Fai Della Paganella, we find nature guides specialized in "balance excursions" and a "Parco del Respiro". It is precisely this region, in the last few years, has put a lot of emphasis on full immersion experiences in nature, including forest bathing.

But that's not all, also in Piedmont within the Zegna Oasis, we find three paths dedicated to forest bathing, which are unique in Europe.

Japan History: Eugène Collache

Eugène Collache (29 January 1847 Perpignan - 25 October 1883 Paris) was an officer in the French Navy of the 19th century. He left the Minerva ship in the port of Yokohama with Henri Nicol to rally other French officers, led by Jules Brunet, who had embraced the Bakufu cause in the Boshin war. On November 29, 1868, Eugène Collache and Nicol left Yokohama aboard a commercial ship, the Sophie-Hélène, chartered by a Swiss businessman.

Eugène Collache, between France and Japan

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Eugène Collache and Boshin's war in Japan

Eugène Collache and Henri Nicol first reached Samenoura bay in Nanbu province (modern Miyagi prefecture), when imperial forces had subdued the daimyō of Northern Japan and that those in favour of the shōgun had fled to the island of Hokkaidō. In Aomori, they were warmly welcomed by Tsugaru's daimyō. An American ship warned them of an arrest warrant against them and Eugène Collache, always with his friend Henri Nicol, decided to board that American ship to reach Hokkaidō.

During the winter of 1868-1869, Eugène Collache was commissioned to establish fortifications in the volcanic mountain range to protect Hakodate.

The surprise attack on the Imperial Navy, in which Collache participated in the battle of Miyako, occurred on May 18. Collache was on the ship Takao, while the other two ships were the Kaiten and the Banryū. The ships encountered bad weather, so the Takao reported engine problems and the Banryu returned to Hokkaido, without joining the battle.

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Kaiten instead planned to enter the port of Miyako with an American flag. Due to engine problems, Takao was sailing after him and at that moment Kaiten joined the battle for the first time by raising the Bakufu flag a few seconds before boarding the imperial warship Kōtetsu. The Kōtetsu managed to repel the attack with a Gatling gun and the Kaiten came out of Miyako bay just as Takao entered it. Eventually, Kaiten fled to Hokkaidō, but Takao was unable to leave the pursuers and was destroyed

At that point, Collache tried to escape with the favor of the mountain, but surrendered after a few days together with his troops to the Japanese authorities. They were taken to Edo for arrest. Collache was judged and sentenced to death, but eventually pardoned and transferred to Yokohama aboard the French Navy frigate Coëtlogon, where he joined the French rebel officers led by Jules Brunet.

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Return to France

Returning to France, he was discharged from the military and called a deserter, but the sentence was light and he was allowed to return to the list for the Franco-Prussian war together with his friend Nicol.

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Books

The experience in Japan was very important, so Eugène Collache wrote "An Adventure in Japan 1868-1869" ("Une aventure au Japon 1868-1869"), which was published in 1874.

Untranslatable words: Mono No Aware, Shakkei, Hikikomori, Omotenashi, Betsubara

It happened to everyone at least once to surf the internet and find articles about "untranslatable words". In fact, we often discover that every nation has special words with a certain meaning without any correspondence in its own language. Today we at Japan Italy Bridge want to try to summarize those special, unique and sometimes magical words that enclose an entire world.

Untranslatable words: Mono No Aware, Shakkei, Hikikomori, Omotenashi, Betsubara

Author: Sara

photo credits: Unsplash

Untranslatable words: Mono No Aware

The first on the list of our untranslatable words is 物の哀れ, "mono no aware". An aesthetic concept that expresses strong emotional participation in the beauty of nature and human life with a consequent nostalgic feeling linked to its incessant change. So literally we could translate it as "the pathos of things" or "the beauty of the ephemeral".

Mono no Aware finds its roots in the Heian period, but it spread only in the Edo period when the scholar Motoori Norinaga made a careful analysis and criticism of Murasaki Shikibu's "The Tale of Genji" defining it as a perfect example of "mono no aware", the perfect essence of Japanese culture. From this moment on, the creative path of many Japanese artists has had as its pivot this strange and complex concept. In fact, we find extremely sentimental the "transience" of things to take over, both in literary as well as cinematographic works. This leaves that feeling of "lack" for an ending that neither the reader nor the spectator is satisfied with. A sweet sadness and awareness that everything is destined to die slowly (and for this reason it must be loved deeply).

Shakkei

photo credits: wikipedia.org

The second expression we want to analyze is 借景, "shakkei". This time it is a particular technique literally defined as "landscape on loan", i.e. incorporating external elements of the landscape into the composition of a garden, the perfect fusion of the available elements already present with the surrounding aesthetics.

We could say that the whole of Japan refers to the concept of "Shakkei". Everything seems to be exactly in the right place in a harmonious and not shamelessly calculated and studied way. A sort of exaltation of nature as if even skyscrapers were an integral and perfect part of the whole landscape. In reality, however, this expression refers purely to the gardens of East Asia, which gives them the charm we know well. The principles of "borrowed landscape" have their roots in the Sakuteiteki (ancient Japanese gardening treatise), which developed further and further until it reached its maximum popularity during the Meiji and Taisho periods.

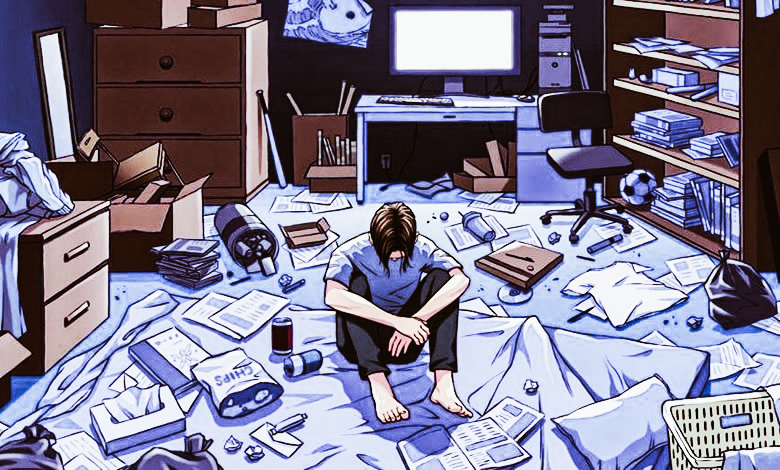

Hikikomori

photo credits: emefka.sk

The third word is perhaps among the best known and most "dangerous". We are talking about 引き籠もり, Hikikomori. Today it is a sad social phenomenon that can have extreme consequences and goes beyond mere "isolation". There are people who decide to voluntarily withdraw from social life, seeking extreme levels of loneliness by assuming a deleterious lifestyle both physically and psychologically. Night and day are reversed, direct relationships are often replaced by virtual ones or, in even more extreme cases, none at all. The hikikomori wanders around his room, devoid of any stimuli and this, as is intuitable, are characteristics that distinguish depressed subjects with obsessive-compulsive attitudes.

The first to give a name to this particular phenomenon was the psychiatrist Tamaki Saitō when he observed that the number of those who presented this deep lethargy towards life increased and the characteristics were always the same. Therefore, we can define Hikikomori as a syndrome rather than a word in itself.

Untranslatable words: Omotenashi

photo credits: livingnomads.com

The fourth on the list is お持て成し, "omotenashi". It is really difficult to find an equivalent that can even give an idea of this wonderful concept. We could use the word "hospitality", but it is almost reductive. This word expresses one of the most complex and profound aspects of Japanese culture. Omotenashi is the will to be attentive and take care of others. It also means to give importance to details, to be aware of one's own actions, to have the sensibility to seek harmony and to make others feel good. It was the Buddhist monk Sen no Rikyū who established the principles and good rules of conduct during the famous tea ceremony, an expression of the utmost care towards the guest.

There fore, Omotenashi is a reflection of Japan, the basis on which the behavioural etiquette of the entire country is rooted. Even if it is not said that this sense of "hospitality" is always encountered (the whole world is a country: there are also very unfriendly Japanese!), but you can easily perceive it when you experience it.

Betsubara

photo credits: lickthatspoon.blogspot.com

The last term we will address today is べつばら, "betsubara". It's a word that can make you smile and literally means "separate stomach." This is where all dessert goes when you say you can't eat another bite, but you eat it anyway. It's a bit like when you say, "there's always room for dessert" even though you already feel totally full. Obviously it can be understood for any food you have a weakness for: it can be ramen, sushi, pizza. So everyone has a different "betsubara"! Which one is yours?

The shōchū and its infinite pairings

If you follow us closely, you've surely heard about shōchū several times. I’m about to make a small recap just to remind you what we are talking about: shōchū is a distillate made from barley, sweet potatoes or rice. Generally, it contains 25% alcohol so it is lighter than vodka but stronger than wine. The production area of this distillate is the island of Kyūshū, but today it’s produced practically everywhere in Japan.

The shōchū and its infinite pairings

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: japantimes.co.jp

The pandemic caused by COVID-19 has caused or even just resurrected many fears in the minds of many, from the fear of dying to the much lighter fear of gaining weight.

We are all, even more, looking for everything that can be healthy... well, it seems that shōchū may be just one of the things we should be looking for. Shōchū expert Stephen Lyman, the author of the book "The Complete Guide to Japanese Drinks" also nominated for a James Beard Award, has replaced beer and wine with shōchū and thanks to this he has lost seven kilos in seven months! Obviously, if we give importance to weight loss, it is absolutely not for an aesthetic issue, but to avoid serious diseases such as obesity.

The shōchū in 2003 has reached a sales volume even higher than the sales of sake! Its popularity is growing, driven also by its alleged medical benefits - ranging from the prevention of blood clots to the containment of obesity - which make it a healthy alternative to other alcoholic beverages.

photo credits: japantimes.co.jp

Lyman, a native of New York, discovered this beverage in an izakaya bar in Manhattan more than 12 years ago and it was love at first sight. Lyman explains: "I've always loved wine and craft beer. Distilled drinks were a bit too strong for me and I was always looking for a drink that would have been perfect with food".

Shōchū is good for diet too

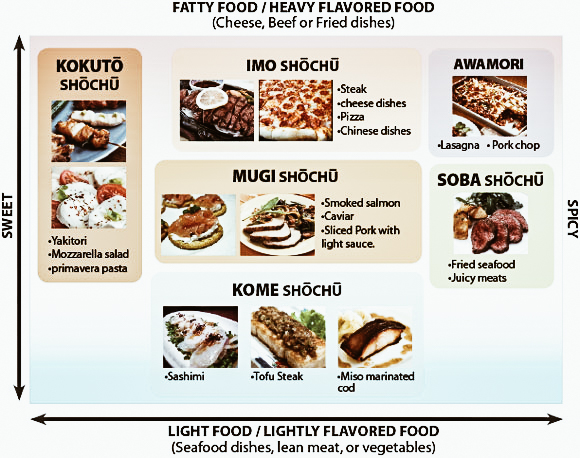

In 2011 Lyman's interest in shōchū became a real passion, and he started drinking it, even more, when a sports injury caused him a gain of weight. "I knew that shōchū was low-calorie, so I decided to give up wine and beer for shōchū six days per week," he says. Within a month, Lyman lost two kilos; after two months, five. Because of this, having found the shōchū could make him lose weight without altering his lifestyle, he began to take an interest in this Japanese drink and all possible pairings. Lyman says that the pairing of shōchū is possible with more than 50 possible ingredients! Richer shōchū notes work with heavier foods and, in particular, with miso dishes.

The barley shōchū obtained by vacuum distillation with a lighter and more aromatic style is perfect with white fish dishes, delicately flavoured sashimi and simmered. In general, the sweet-potato shōchū instead goes well with meat such as pork, while the kokutō (black sugar) shōchū, which is similar to rum, harmonizes with grilled meat. The full taste of shōchū is a surprising accompaniment to dark chocolate.

Also, the Iichiko Silhouette also called "the Johnnie Walker of shōchū" tastes like stone fruit and paired with soda water can be served with watermelon and mint soup. The shōchū Yamatozakura resists the sweet and earthy spices of Taiwanese braised pork with aniseed and cinnamon, while the Komaki Issho Bronze, a shōchū of sweet potatoes easy to eat, goes perfectly with a vegan stew of sweet potatoes, chickpeas and peanuts.

photo credits: mtcsake.com

But let's go more specifically and analyze some of the tastiest combinations:

Imo, sweet potato shōchū

Pork chops, pizza Margherita, fried tempura

Imo has a sweet aroma and taste, which goes well with substantial dishes or fried foods. It also is good with rich Chinese food or pizza with lots of cheese.

Mugi, derived from barley

Smoked salmon, caviar, sliced pork with lemon sauce

The mugi has a very clean and fresh taste. Technically this drink goes well with any kind of food, but it tastes better with a simple dish than with an oily dish. The aroma of barley enhances the vegetable sauce.

Kome, from rice

Sashimi, trout marinated in miso, tofu steak.

The kome has an umami (flavor) that goes well with any kind of food but particularly indicated with the delicacy of sashimi. It can also be enjoyed with rice dishes.

Kokuto, sugar cane shōchū

Yakitori (grilled chicken), pasta primavera, mozzarella salad

The Kokuto is made with sugar cane and can taste a bit fruity. The fragrance of kokuto is similar to the one of sweet syrup, but the taste is very simple and delicate and not extremely sweet. This particular taste can bring out the original flavours of the food and is indicated with soy sauce dishes that have a slight sweetness.

Awamori shōchū

Porkchop, lasagna, banana pancake

Awamori has a special aroma and rich flavour that goes well with spicy or heavy foods such as cheese and creamy dish.

Soba shōchū

Penne arrabbiata, fried oysters, meatballs

The characteristics of soba are very mild and clear-cut but at the same time a little bit bitter. This can be enjoyed with slightly spicy foods or juicy meats.

I'm sure that as soon as you've finished reading this article you're already looking for the perfect shōchū for you, are you ready for a completely new adventure and completely different lunches and dinners?