Senchadō: l'arte raffinata del tè in foglia giapponese

Quando si parla di tè giapponese, la mente vola subito al matcha e alla sua cerimonia codificata. Ma c'è un'altra tradizione, meno conosciuta ma altrettanto affascinante: il Senchadō, l'arte di preparare e gustare il sencha, il tè verde in foglia più diffuso in Giappone.

Una cerimonia più libera e moderna

Rispetto alla rigida formalità della Cha-no-yu, la cerimonia del matcha, il Senchadō si distingue per un approccio più spontaneo e intimo. Nato nel periodo Edo grazie agli studiosi confuciani, si diffuse tra i letterati come un rituale raffinato ma accessibile, dove il piacere della conversazione si unisce alla degustazione del tè.

L'arte della preparazione

Nel Senchadō, tutto ruota attorno alla precisione e all'armonia. Si utilizza una teiera kyūsu, perfetta per controllare il flusso dell'acqua, e il tè viene infuso a temperature più basse rispetto ad altre varietà, per esaltarne la dolcezza e l'umami. Ogni versata ha un significato, e l'eleganza del gesto diventa parte dell'esperienza.

Un viaggio di sensi e cultura

Più di una semplice bevanda, il Senchadō è un'arte che invita a rallentare e ad apprezzare il momento presente. Il profumo erbaceo del sencha, il colore dorato della sua infusione e il sapore delicato si fondono in un rituale che trasmette equilibrio e benessere.

Dove sperimentarlo

In Giappone, alcune scuole tradizionali offrono esperienze di Senchadō, mentre in città come Kyoto e Tokyo esistono sale da tè specializzate. Anche a casa, con il giusto tè e un po' di attenzione alla preparazione, è possibile avvicinarsi a questa raffinata pratica.

Scoprire il Senchadō significa entrare in contatto con una dimensione meno nota della cultura giapponese, fatta di gesti eleganti e gusto autentico. Siete pronti a versare la vostra prima tazza?

Sakè: tre curiosità sulla bevanda simbolo del Giappone

Il sake non è semplicemente un alcolico: è un autentico pezzo di cultura giapponese, strettamente legato alla storia, alle tradizioni e persino alla spiritualità del Paese del Sol Levante. Sebbene venga spesso definito "vino di riso", la sua produzione è tutta speciale e il suo significato va ben oltre il semplice gusto. Per parlare delle bevande a base di riso, l'ideogramma sake [酒] si riferisce in generale all'alcool, ma viene pronunciato shu. Quando i giapponesi parlano di bevande realizzate con il riso, usano il termine nihonshu [日本酒], che significa "bevanda del Giappone".

E ora, preparatevi a scoprire tre curiosità affascinanti che vi faranno vedere il sake sotto una luce completamente nuova!

1. Il sake non è un distillato

Molti credono che il sake sia simile ai liquori o ai distillati, ma in realtà il suo processo di produzione è più vicino a quello della birra. Il riso utilizzato viene prima levigato per eliminare le impurità, poi cotto a vapore e fatto fermentare grazie a un fungo speciale chiamato koji. Questo trasforma gli amidi in zuccheri, permettendo al lievito di avviare la fermentazione alcolica.

Il risultato? Una bevanda dal gusto complesso e delicato, con una gradazione alcolica che si aggira tra il 13% e il 16%. E se pensavate che esistesse solo un tipo di sakè, ripensateci: ne esistono varianti più leggere, non filtrate, frizzanti e persino invecchiate!

2. Un legame con il sacro

Il sake non è solo un piacere per il palato, ma anche un elemento profondamente radicato nelle tradizioni religiose giapponesi. Antiche leggende narrano che persino gli dèi lo apprezzavano: si dice che il dio delle tempeste Susanoo-no-Mikoto abbia sconfitto un drago offrendogli otto barili di sake.

Ancora oggi, questa bevanda viene usata nei rituali shintoisti, specialmente nei matrimoni e nelle offerte ai kami (le divinità giapponesi). Durante alcuni festival, come il Doburoku Matsuri, viene distribuito un sakè non filtrato ai partecipanti, creando un legame tra il sacro e la convivialità.

3. Il galateo del sake

Non basta riempire un bicchiere e bere, il sake ha un vero e proprio codice di comportamento. Tradizionalmente si beve in piccole tazzine di ceramica (choko) o in eleganti scatoline di legno (masu). Ma la regola d’oro è una: mai versarselo da soli! È un gesto poco educato, mentre versarlo agli altri è un segno di rispetto e condivisione.

Anche la temperatura conta: d’inverno si può gustare caldo, mentre nei mesi estivi è più apprezzato fresco o persino freddo. Ogni metodo di servizio esalta aromi diversi, rendendo ogni sorso un’esperienza unica.

Un brindisi alla tradizione!

Il sake non è solo una bevanda, è un viaggio nella cultura giapponese. La prossima volta che avrete l’occasione di assaggiarlo, ricordatevi di alzare la tazzina e brindare con un tradizionale "Kanpai!" – e magari stupire i vostri amici con queste curiosità!

Il nostro rapporto con il Sake

Japan Italy Bridge si è spesso dedicata alla promozione del sake, portando avanti numerose iniziative, tra cui la Bunka Academy. L’obiettivo è stato quello di far conoscere anche in Italia la consapevolezza di come apprezzare il sake, sottolineando che non si tratta di una grappa, ma di un vero e proprio vino. Non è una bevanda da consumare solo a fine pasto, ma da gustare durante tutta la cena. A differenza del vino, il sake non copre i sapori dei piatti, ma li esalta. Per questo motivo, Japan Italy Bridge ha organizzato eventi in collaborazione con esperti giapponesi, che hanno condiviso con il pubblico la storia, il processo di produzione e i segreti del consumo e della conservazione del sake.

Se siete curiosi, vi invitiamo a dare un’occhiata al nostro portfolio e scoprire tutte le collaborazioni che abbiamo portato avanti.

Alla scoperta delle tre grandi varianti di soba in Giappone

La soba, i tradizionali noodles di grano saraceno, è uno dei piatti più iconici della cucina giapponese. Pur essendo diffusa in tutto il Paese, ogni regione ha sviluppato la propria variante, con caratteristiche uniche che la rendono speciale. Ecco tre delle versioni più famose che vale la pena assaggiare durante un viaggio in Giappone!

1. Togakushi Soba – La delicatezza montana di Nagano

Nel cuore delle Alpi giapponesi, la regione di Nagano è rinomata per la qualità della sua soba, in particolare quella di Togakushi. Questa versione si distingue per la lavorazione artigianale e la presentazione: i noodles vengono serviti freddi su un vassoio di bambù chiamato “zaru”, accompagnati da una salsa a base di soia (tsuyu) e spesso arricchiti con daikon grattugiato e wasabi. La purezza dell’acqua di montagna utilizzata nella preparazione contribuisce a donare un sapore fresco e raffinato.

2. Izumo Soba – Il gusto intenso del Giappone occidentale

Originaria della prefettura di Shimane, l’Izumo soba ha una consistenza più robusta e un sapore deciso grazie all’uso della farina di grano saraceno intero, che conserva il colore scuro e l’aroma naturale del cereale. Un tratto distintivo di questa varietà è la sua modalità di servizio: spesso presentata nel “warigo”, tre piccoli contenitori impilati, nei quali si versa direttamente la salsa e i condimenti, creando un mix di sapori ad ogni boccone.

3. Wanko Soba – Un’esperienza gastronomica unica a Iwate

Più che un semplice piatto, il Wanko soba è una vera e propria sfida culinaria. Tipica della prefettura di Iwate, questa specialità prevede il servizio di piccole porzioni di soba in ciotole individuali, che vengono continuamente riempite dal personale finché il commensale non si arrende. È un’esperienza divertente e interattiva, perfetta per chi vuole mettersi alla prova mentre assapora il gusto autentico di questa varietà regionale.

Se siete amanti della cucina giapponese, provare queste tre versioni di soba è un’occasione imperdibile per scoprire la diversità gastronomica del Paese. Ogni regione offre non solo un sapore unico, ma anche un’esperienza culturale che arricchisce ogni viaggio! Potete approfittare delle nostre proposte e offerte cliccando QUI: Your Japan vi farà venire l’acquolina in bocca!

Japan History: Furuta Shigenari

Furuta Shigenari (Motosu District, Gifu Prefecture, 1544 - July 6, 1615) was a Japanese warrior who lived during the Sengoku period. He was the son of tea ceremony master Furuta Shigesada (known by his Buddhist name Kannami, later renamed Shuzen Shigemasa) who was also one of the younger brothers of the lord of Yamaguchi-jo Castle in Motosu-gun County, Mino Province. While pursuing a career as a warrior, Oribe also acquired a sophisticated taste for the tea ceremony from his father and seems to have been adopted by his uncle.

Furuta Shigenari, the samurai who was also a master of the tea ceremony

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credit: https://it.wikipedia.org/

Furuta Shigenari became Oda Nobunaga's servant when Nobunaga attacked the Mino province in 1567. In 1569, Shigenari married Sen, one of the younger sisters of Nakagawa Kiyohide (the lord of Ibaraki-jo castle in Settsu province).

In 1576, Oribe became an administrator of Kamikuze no sho (now, Minami-ku Ward of Kyoto City), Otokuni-gun district, Yamashiro province. He later joined Hashiba Hideyoshi's (later Toyotomi Hideyoshi) army during the attack on Harima Province and Akechi Mitsuhide's army during the attack on Tanba Province, making a successful career as a war leader despite his small salary of 300 koku.

As a master of the tea ceremony, he is widely known as Furuta Oribe. His common name was Sasuke, his first name was Keian. The name 'Oribe' as master of the tea ceremony originated from the fact that he was awarded the rank of Junior Fifth Rank, Lower Grade, Director of Weaving Office.

During the period of his union with Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Furuta Shigenari met master Rikyū and became one of his favourite pupils for about ten years during which he wrote two works: Oribe Densho ("The Book of Secrets") and Oribe Hyakka ("The Hundred Precepts"). His relationship with Rikyū was so intense that he was not afraid to disobey the common lord Hideyoshi when Rikyū left in exile for Sakai. During Toyotomi Hideyoshi's rule, the generation of tea masters of the Nobunaga period, Yamanoue Sōji, Sen no Rikyū, Tsuda Sogyu, Imai Sokyu, died out in a few years. All the tea masters were philosophical and political opponents of the military expansionism of warlords such as Hideyoshi, and the importance of the discipline of tea placed them in great social and political authority, so, like Rikyu, they were exiled or forced to commit suicide. The art of tea, once Nobunaga's generation ended, became a state ceremony in the Tokugawa Restoration period and Furuta Shigenari became the most important tea master of the new generation. He also taught the shōgun Tokugawa Hidetada, Kobori Enshū and Honami Kōetsu. However, accused of plotting a conspiracy against the Tokugawa, he was ordered to commit seppuku in 1615.

The influence

Furuta Oribe's influence encompassed all ceremonial practice from the practice of tea preparation, to artistic and architectural styles, furniture and the style of ceramics.

In fact, Oribe-ryū was the style of ceremony he oversaw, as was the style of Oribe-yaki ceramics. He also designed a type of lantern (tōrō) for the tea garden, known as Oribe-dōrō.

Here comes the Kimono Experience at TENOHA Milano

Here comes the KIMONO EXPERIENCE with Giappone In Italia, Milano Kimono and TENOHA Milano!

The Giappone In Italia Association has created a unique experience in collaboration with Milano Kimono and TENOHA Milano, we are talking about the KIMONO EXPERIENCE!

Feel the real Japan with the Kimono Experience

Author: SaiKaiAngel

Do you feel like spending some unique, timeless moments? At a time when everything is hectic, why don’t we take a moment for ourselves? Without commitments, stress or confusion? Let's immerse ourselves in the love of Japan and do it in the best possible way! Have you ever wondered "But how would I look in a yukata or a kimono?" I think so, at least, I've asked myself that many times and finally managed to see myself in traditional Japanese dress! As you know, Giappone In Italia Association, TENOHA Milano and Japan Italy Bridge are working with a common focus: building a bridge between Japan and Italy by promoting Japanese culture here.

An absolutely special experience that will allow you to feel in Japan. If you can't take the plane, how can you experience Japan? You can do it as always in the corner of Japan here in Italy, TENOHA Milano! Not only that, from 15 to 30 June, you can enjoy the "KIMONO EXPERIENCE"! What is it about exactly?

What is it?

The KIMONO EXPERIENCE is an exhibition at TENOHA Milano from 15 to 30 June, featuring the most beautiful kimonos and photos by Alberto Moro, President of Japan in Italy and author of the book 'Il mio Giappone'. You will find photos of people who wanted to wear kimonos in the streets of Milan even without being Japanese! This is the aim of KIMONO EXPERIENCE, to make non-Japanese people live the emotion of the Rising Sun, not only around, but also on them. Yes, because if you book your place, you can have the joy of wearing a yukata and being photographed by none other than the President of Japan in Italy, Alberto Moro, who is, as you know, also a famous photographer.

Imagine yourself in the Japanese atmosphere, wrapped up in a yukata (kimono summer version) that the dressmaker Yurie Sugiyama will have you put on, photographed by Alberto Moro in the incredible and Japanese TENOHA Milano. A dream? No! A reality that is waiting for you!

You can visit the exhibition from 15 to 30 June, from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m., in the TENOHA Milano pop-up space at Via Vigevano 18.

If you would like to dress up and have your photo taken in yukata, remember that the dress-up teacher Yurie Sugiyama will be available from 17 to 20 and from 24 to 27 June, from 10.30 am to 1 pm and from 3 to 6 pm. Although the fitting will be free of charge, in the form to be filled in below, you will be asked for a booking deposit which will be returned when you show up at the KIMONO EXPERIENCE!

Not only that! If you wish, you can buy your photo in kimono as a unique and unrepeatable souvenir of the day. They will surely ask you when you flew to Japan, because these are moments that can hardly be repeated here in Italy.

KIMONO EXPERIENCE, un’esperienza da non perdere, per portare nuovamente il Giappone In Italia, come recita il nome dell’Associazione che l’ha creata.

Obviously we at Japan Italy Bridge look forward to seeing you there!

>> BOOK NOW YOUR KIMONO EXPERIENCE! <<

Subject to availability.

photo credits: Alberto Moro, Presidente Associazione Giappone in Italia

Japan History: Fukushima Masanori

Fukushima Masanori (1561 - August 26, 1624), whose name was originally Ichimatsu, was born in Owari Province.

Fukushima Masanori, one of the Seven Spears of Shizugatake

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credit: wikipedia.org

Son of Fukushima Masanobu, Fukushima Masanori was a Japanese general and daimyō in the service of the Tokugawa, also famous for being one of the Seven Spears of Shizugatake. It is also said that he may have been a cousin of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Masanori stormed Miki Castle in Harima Province and, during the Battle of Shizugatake in 1583, defeated Haigo Gozaemon and had the honour of taking the first head, that of the enemy general Ogasato Ieyoshi.

Fukushima Masanori took part in many of Hideyoshi's campaigns; it was after the Kyūshū campaign (1586-1587) that he became daimyō, receiving the fief of Imabari in Iyo province; shortly afterwards he took part in the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592-1598) and distinguished himself once more during the Battle of Chungju.

Following his involvement in the Korean campaign, Masanori was involved in the search for Toyotomi Hidetsugu. He led 10,000 men in 1595, surrounded the Seiganji temple on Mount Kōya and waited for Hidetsugu to commit suicide. On Hidetsugu's death, Masanori received Hidetsugu's former fief of Kiyosu in Owari province.

Being hostile to Ishida Mitsunari, Fukushima Masanori came into sympathy with Tokugawa Ieyasu; Ishida burned Masanori's castle on a pretext and during the Battle of Sekigahara launched the first attack on Ukita's troops, remaining in the front line throughout. Having won the battle and captured Ishida, Masanori beheaded the enemy daimyō in Kyoto along with Anko and Konishi. Masanori received the fief of Hiroshima in Aki, but Ieyasu never fully trusted Masanori, so he ordered him to rebuild the Nagoya castle so that he could spend some of his income.

At that point, Masanori asked to take part in the siege of Osaka (1614-15), but was forced to remain in Edo. The new Shōgun, Hidetada, trusted Masanori even less and, after Ieyasu's death, accused him of misrule and transferred him to the fief of Kawanakajima. Fukushima Masanori's younger brother Masayori had already been deprived of his fief at Yamato in 1615.

Il posto di comando di Fukushima Masanori a Sekigahara

photo credit: samurai-world.com

It seems that his descendants became hatamoto in the service of the Tokugawa shogunate. The hatamoto were samurai under the direct control of the Tokugawa Shogunate in feudal Japan. All three shogunates in Japanese history had direct contacts, only in earlier shogunates they were called gokenin. However, in the Edo period, the hatamoto were the senior vassals of the Tokugawa dynasty and the gokenin were the junior vassals.

Fukushima Masanori owned one of the three great spears of Japan: Nihongo, or also called Nippongo (日本号). Used in the Imperial Palace, the Nihongo was later owned by Masanori Fukushima, and then passed into the hands of Tahei Mori. It was recovered, restored and is now in The Fukuoka City Museum.

Japan History: Chōsokabe Motochika

Chōsokabe Motochika (1538 - 11 July 1599) was a Japanese daimyō of the Sengoku period and was born in Okō Castle in the Nagaoka district of Tosa province. The eldest son of Chōsokabe Kunichika, Chōsokabe Motochika was such a sweet boy that his father was worried about his nature, and it seems he was nicknamed Himewako, "Little Princess", by his vassals.

Chōsokabe Motochika, also known as Himewako

Author: SaiKaiAngel

photo credits: wikipedia.org

Despite these concerns, Chōsokabe Motochika proved to be a skilled and brave warrior in his first battle, defeating the Motoyama clan in 1560 at the Battle of Tonomoto. After defeating the Motoyama and forming alliances with local families, Chōsokabe Motochika was able to build his power base on the Kōchi Plain. While remaining loyal to the Ichijō, Motochika with a force of 7000 men marched on the Aki clan, rivals of the Chōsokabe, defeating them in 1569 during the Battle of Yanagare. At that point Chōsokabe Motochika could concentrate on the Ichijō.

During the rule of the Hata district of Tosa, Ichijō Kanesada was a very unpopular leader and because of this, Motochika wasted no time in marching on the Ichijō headquarters in Nakamura and in 1573 Kanesada fled. At that point, the Ōtomo clan provided Kanesada with a fleet and with that he returned, leading an expedition that the Chōsokabe defeated at the Battle of Shimantogawa. At this point Kanesada submitted to the Chōsokabe, who probably had him assassinated in 1585.

Chōsokabe Motochika became the sole ruler of Tosa, and one of the problems the Chōsokabe faced was their own territory. Because of his poverty, he was unable to pay his generals, so he began to look to neighbouring provinces.

The unification of Shikoku

After the conquest of Tosa, Chōsokabe Motochika prepared for an invasion of the province of Iyo, against the lord of that province Kōno Michinao, a daimyō who had been driven from his domain by the Utsunomiya clan, helped only by the Mōri clan. But at this time the Mōri clan was at war with Oda Nobunaga, so they were unable to help Michinao, however the campaign in the Iyo province was not easy.

In 1579 a Chōsokabe army of 7000 men, led by Hisatake Chikanobu, attacked Okamoto Castle, held by Doi Kiyoyoshi in southern Iyo. During this siege, Chikanobu was killed and his army defeated. Motochika returned the following year with some 30,000 men to Iyo and forced Michinao to flee to Bungo province. With the Mōri and Ōtomo engaged on other fronts, Motochika was free to continue his conquest of the island and in 1582 was able to continue his raids on the Awa province to defeat the Sogo clan, giving him control of the island in 1583.

photo credits: mvbennett.wordpress.com

In 1579 Chōsokabe Motochika entered into communication with Nobunaga who seemed to have praised him, although in private he referred to him as a bat on a birdless island and planned to conquer Shikoku in the future, planning to give it to his son Nobutaka. This did not happen, due to Nobunaga's death in 1582.

Involved in the ensuing dispute between Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu the following year, he promised Tokugawa his support, although he made no direct moves to that end. Hideyoshi instead sent Sengoku Hidehisa to block any interference from Motochika. The Komaki campaign between Hideyoshi and Ieyasu ended in a peace treaty, and in 1584 Hideyoshi invaded Shikoku with 30,000 troops from the Môri clan and another 60,000 from Hashiba Hidenaga. Motochika managed to retain control of the Tosa province thanks to the terms decided by Hideyoshi.

Chōsokabe Motochika is remembered both for his 100-article Code of Chōsokabe and for his tenacity in founding a very strong castle-city from Oko to Otazaka and then to Urado. However, the problems caused by Morichika's appointment as heir led to the clan's undoing. After Nobuchika's death in battle, Hideyoshi suggested that Motochika's second son, Chikakazu, be appointed heir.

But when Motochika resigned, he made Morichika, his fourth son, his heir, because he felt Chikakazu was physically incapable of assuming leadership of the family. With this in mind, Chikakazu retired and died of illness in 1587. When Chōsokabe Motochika was called to Hideyoshi's invasion of Kyūshū, he and Sengoku Hidehisa were called in.

Their mission was to raise the siege of the Ōtomi clan. Despite the wise advice of Chōsokabe Motochika, generals Ōtomo and Sengoku did not adopt a defensive position and attacked the forces of the Shimazu clan at the Battle of Hetsugigawa, defeating the allied troops, but at the same time Nobuchika, Motochika's heir, died. At that point Toyotomi Hideyoshi praised Motochika's thinking and offered him Ōsumi as compensation for his loss, but this was refused.

In 1590 Motochika led a naval contingent in the siege of Odawara and in 1592 commanded 3000 soldiers in the invasion of Korea. On his return from Korea he retired to Fushimi, became a monk and died on 11 July 1599.

Sakura, an in-depth look at the flower symbol of Japan

We continue our series of in-depth articles dedicated to the Japanese culture and today we talk about Sakura, the flower symbol of the Rising Sun. "The perfect flower is a rare thing. One could spend a lifetime looking for it, and it would not be a wasted life."

Sakura 桜 Symbolic flower of Japan

Guest Author: Flavia

This is how Ken Watanabe began in a scene from the famous film 'The Last Samurai' (2003) as the rebel samurai Katsumoto, against the backdrop of a beautiful Japanese garden. How could we not remember this scene from the film which, despite some historical inaccuracies, is able to give us moments like this. Surrounded by splendid trees in bloom, Katsumoto-Watanabe is simply staging the prototype of Japanese aesthetic sensitivity towards nature. In this case, towards flowers. But here we are talking about one flower in particular... the cherry blossom, an undisputed object of age-old admiration: the Sakura (桜 - さくら).

We are all familiar with cherry blossoms: their beauty is obvious, admiring them a natural consequence. This, I would say, needs no explanation. We can, however, talk about the particular importance of this delicate little flower in Japan, so much so that it has become a "moral" symbol (the official one is the chrysanthemum).

The term 'Sakura' refers to both the flower and the tree - known as the 'Japanese cherry tree' - a type of cherry tree characteristic of the Far East. There are about a hundred varieties of Sakura in Japan, including the big cities. But the most common are the Yamazakura and especially the (Somei-) Yoshino, with its typical pale pink-white colour, which has been admired by the Japanese for hundreds of springs.

photo credits: japan.stripes.com

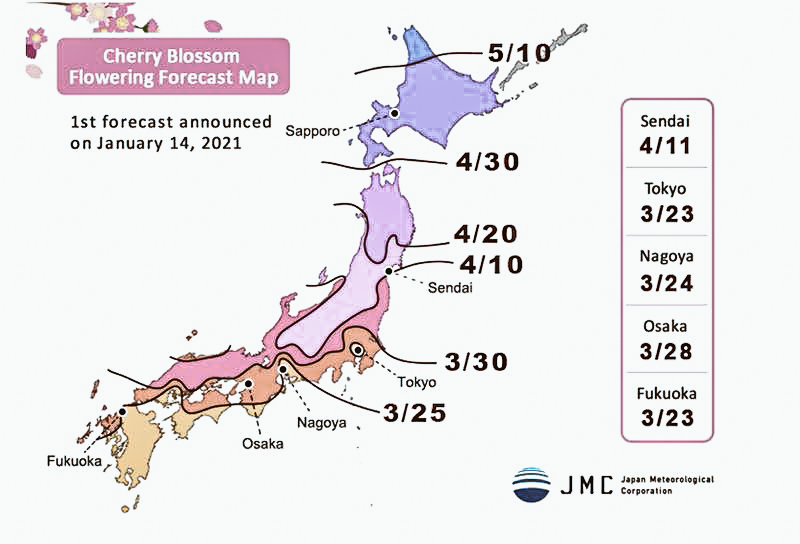

The Sakura is an institution in Japan, with its own special symbolism and deep meaning. It appears on the famous 100 yen coin and frames Fuji san, Japan's other great symbol, on the back of the current 1000 yen note. It is so popular that the National Meteorological Agency issues a special Sakura Zensen ( 桜前線 ) bulletin every year to update on the status of the flowering. The media informs the population daily about the best spots, so that they can adjust for the beloved Hanami (flower-gazing) activity, deciding where and what variety of Sakura to see.

Flowering proceeds from south to north, as the climate is milder in southern areas. So if you arrive in Japan when the flowering has already passed in the centre-south, look at the calendar, you might still be in time to catch them in Hokkaidō!

Mankai 🌸 Flowering

The average flowering time varies according to geographical location, but in any case it is short: a few days, maximum ten days. It starts in Okinawa, around the end of January, gradually moving northwards with the last buds opening around mid-May in Hokkaidō. This is the approximate time period. Bad weather, disturbances or sudden changes in temperature can obviously affect the duration of flowering, given the extreme delicacy of the little flower. It all depends on the climate and the year: it can happen that the flowers bloom a little earlier or later, or that the blooming is interrupted by a sudden change in climate. The time of the flowering boom is known as Mankai (満開), which in fact means 'full opening'.

photo credits: japan.stripes.com

As mentioned above, most cherry trees are of the Somei-Yoshino variety, but there are over a hundred species. Some are even capable of producing edible fruit. Of the criteria for distinguishing between the different types, the most immediate is undoubtedly the number of petals, which can be ten, twenty or even more. The most common are the classic five-petalled Sakura, both wild and cultivated.

🌸 Types of Sakura

But let's look at some examples of more unusual cherry trees. In addition to Somei-Yoshino, the most cultivated and popular, we can find:

- Yama-zakura (山桜), the 'Mountain Cherry'. Very popular, it ranks right after Somei-Yoshino in terms of popularity. It has large pink buds and five petals.

- Fuyu-zakura (冬桜), or "Winter Sakura". As the name suggests, it is a cherry tree that begins to blossom in autumn and continues in winter, although not continuously.

- Yae-zakura (八重桜), the "Double Cherry Tree". So called because of its 'reinforced', i.e. very full-bodied, bud with more than five petals. It is associated with the ancient capital Nara (奈良).

- Shidare-zakura (枝垂桜), i.e. "weeping cherry tree" because its branches fall, like a willow, creating a cascade of pink flowers. It is the official flower of the Kyoto prefecture.

- Ichiyō (一葉), "a leaf". It owes its name to a leaf-like pistil that emerges from its centre when fully open. It is one of those that can have 20 to 40 petals.

photo credits: Akemi K on Flickr, medigaku.com, Pinterest

Ippon-zakura (一本桜) are defined as all cherry trees planted "in solitude". These include Japan's three great cherry trees, the Sandai-zakura (三大桜). The trio consists of the Jindai-zakura in Yamanashi, the Usuzumi-zakura in Gifu and the Takizakura in Fukushima. Jindai and Usuzumi belong to the Edohigan variety (from which Yoshino is also derived), while Takizakura is a weeping cherry tree. In particular, the Jindai-zakura, located in the Jissōji temple (實相寺), is perhaps the oldest in Japan: it is about two thousand years old and has a circumference of 13 and a half metres!

Spring (春), season of hope

The act of contemplating trees in blossom dates back to the Nara period (8th century). Initially the prerogative of the imperial court of Kyoto, over the centuries it was extended first to the category of samurai and then to the rest of the population. Let us say that in the beginning it was the plum tree (梅-Ume) that was the object of attention. The plum tree represented the link with China, as it originated there. But already in the Heian period (8th-12th centuries), due to the interruption of relations with Middle Earth, the Ume was ousted by the more autochthonous Sakura. From then on, spring-themed poems began to refer to Sakura even only as "flowers" (花-Hana) and the word "Hanami" also became interchangeable with "sakura". Linguistic details, however, are indicative.

Spring (春- Haru) has always been characterised as a symbol of rebirth, of generating power.

In ancient times, the blossoming of cherry trees was associated with prosperity, as it presaged an abundant rice harvest. In order to propitiate a good harvest the following year, the beginning of the planting season was opened with a series of rituals ending with joyful celebrations under the Sakura. In the 18th century, Shōgun Yoshimune Tokugawa further promoted this custom by planting Sakura trees in various areas.

Today, spring is the season for students, graduates and undergraduates, who rely on the auspiciousness of the blossom. April marks the start of the new school year for students, while graduates and many school leavers are preparing to enter the world of work. April also marks the start of the new fiscal year in Japan. In short, the cherry blossom season brings with it some beginnings in that land. Therefore, it is duly celebrated with the Sakura Matsuri (桜祭り) festival.

photo credits: Pinterest, Pinterest

Sakura in sweets and delicacies

Sakura and spring are also celebrated through food, in keeping with good Japanese tradition. Famous is the Hanami Bentō (花見弁当), or the bentō that is a must during a picnic under the cherry blossoms. For those who don't know, the bentō is a box for a picnic lunch, used by the Japanese all year round, but in this period it has a Sakura theme. You might find Sakura Onigiri (桜おにぎり) in there, for example, rice balls with salted Sakura on top.

However, there is also cherry blossom tea (桜茶, Sakura-cha), possibly combined with Sakura-Mochi (桜餅), a typical rice cake with red bean paste, wrapped in a salted cherry leaf. Sakura infusion is offered to newlyweds on their wedding day as it is considered a good omen. Wagashi (和菓子) - the traditional Japanese confectionery - come in a variety of sakura-themed varieties. Again, among the more commercial products: just as you can have Matcha-milk, there is also an all-pink Sakura-milk. And we could go on and on, but perhaps we'd better stop, otherwise our mouths will water too much!

photo credits: kitchenbook.jp, pinterest.fr

Hanami (花見), admire the buds

Hanafubuki (花吹雪): "snowy storm of buds". This is how the spectacle of falling petals from cherry trees in bloom is defined, whose rain colours the landscape in a kind of "spring snowfall". If one of these petals (花びら- Hanabira) falls into one's sake glass while making Hanami, it is a propitiatory sign of good health.

As mentioned at the beginning, the word "Hanami" means the practice of looking at cherry blossoms (花= flower(s), 見= watching). Nowadays, Hanami celebrations can range from simple picnics to more elaborate celebrations with music and entertainment. They can also take place at night, in which case, we talk about Yozakura (夜桜) or "sakura by night". The result, you can imagine: an evocative nocturnal Hanami, amid paper lanterns and moonlight.

photo credits: power-shower.com

However, the peculiarity of Hanami is not in simply witnessing this spectacle of nature: it is in assisting it by capturing its fleeting appearance. The beauty of the buds also lies in their transience. In those who contemplate them, a feeling of sweet melancholy arises... which the delicacy of these flowers is able to evoke when, having detached themselves from the tree, they float carried by the wind or a delicate breeze, to then settle on the ground. An emotion given by the realisation that this is nothing other than the ultimate nature of human existence itself: destined, sooner or later, to have an end.

"So I come to this place with my ancestors and a thought comes back to me: like these sprouts we are all dying... recognising life in every breath, in every cup of tea, in every life we take away... " [ Katsumoto Moristugu - The Last Samurai ]

photo credits: YouTube

Symbolism of Sakura: mono no aware (物の哀れ)

The symbolism of Sakura is therefore both sweet and bitter, but this should not surprise us, as we are familiar with the Japanese feeling of "Mono no aware". In other words, a "pathos for things" characterised by a delicate hint of nostalgia, due to the awareness of their constant change. A concept that our Sakura embodies to perfection and of which he inevitably becomes the spokesman. Its beauty is enchanting but evanescent, ephemeral. So contemplation becomes sweet because of the delicacy of the flower, but also melancholic... because it is aware of its evanescence. Thus we contemplate its splendour but with an aftertaste of sadness. In a few words, this is the essence of Sakura.

Once again we are faced with an aesthetic that transcends the exterior. An exterior whose beauty hooks individuals, then leads them to a wider form of contemplation. We have seen this well, also in our article dedicated to Wabi-Sabi 侘寂. This has never been more true than in the case of the Sakura.

Cherry blossoms thus symbolise the transience of life and cyclicity. Because they blossom in all their glory, but their show remains for a limited time. The transience of life, youth and beauty: a metaphor that nature itself seems to want to offer every year and which Japan has been particularly careful to capture. At the same time, however, they are also a symbol of (re)birth and hope... because every year they come back to bloom in all their splendour.

Wonderful and a symbol of vitality on the one hand, extremely fragile on the other: this is their dual nature. Given this awareness, the reference to Buddhism is inevitable.

Symbolism of Sakura: other meanings

Other more specific meanings attributed to Sakura have to do with the number 5. So, naturally, it is the classic five-petalled cherry tree that best lends itself to this type of symbolism. The number 5 is said to recall the Japanese cosmogonic myth (about the birth of the 'cosmos'), according to which there were originally two gods, Izanagi and Izanami, who fathered five children; the birth of the fifth child, the god of fire, would prove fatal to the mother-goddess Izanami. Izanagi, distraught, thus killed this son, from whose parts the mountain gods would then originate. The number 5 also refers to the Japanese esoteric Buddhist concept of the five orientations (cardinal points plus the centre) and the five elements of water, fire, earth, ether and vacuum.

More generally, cherry trees can also be associated with clouds simply because of a visual issue: their mass blossoming can be reminiscent of clouds in the sky. A bit like the expression 'Hanafubuki' we saw earlier, where fubuki (吹雪) alone means 'snowstorm'.

photo credits: Flavia

As the Sakura, so the Samurai

But back to our Katsumoto-Watanabe, his sentence actually ended with "...this is Bushidō". In fact, Sakura was also associated with the ideal of the way of the warrior and the figure of the samurai (侍), so much so that it became the emblem of the category. You will say, where is the similarity? In the fact that the cherry blossom embodied the qualities typically associated with the samurai (courage, purity, honesty, loyalty...). As the Sakura dies at the height of its splendour, so the samurai at the height of his vitality and strength was ready to die if the time came. In this sense, his life, however grand, was as fragile as that of a cherry blossom. However, he was not afraid of death, since it was experienced as a last ideal act and the only possible honourable end, in the name of extreme loyalty to his values.

In the cherry tree, the bushi (warrior) found his model and identified his life with it. Just like the delicate little flower, he had to lead his existence giving his all, through dedication in every gesture, until his last sigh. All that mattered was to "burn" as much as possible through that fuel, which was his life force. In all this, there could be no room for the fear of death. On the contrary, it was in the warrior's last moments that his beauty shone brightest.

So the Sakura, so the bushi: just like in the proverb "Hana wa sakura-gi, hito wa bushi" ( 花は桜木-人は武士 ) that is "Among the flowers the cherry tree, among the people the warrior". The samurai in battle could fall under the blows of the opponent, just like buds that fall to the ground detached from the branches by a gust of wind or rain. Just like so many small, triumphant buds, the samurai flourished, only to meet their fate.

photo credits: Pinterest

This identification was also used in various ways by Imperial Japan centuries later. Among others: the Sakura was reproduced on the sides and in the name itself of the Ōka ( 桜花 ) airplanes to symbolise the extreme act of the Tokkōtai (Special Attack Unit) Kamikaze at the end of World War II. The pilots themselves, on the verge of their suicide mission, are said to have embarked carrying a cherry branch.

Nowadays, the Sakura may symbolise the martial arts.

"Woman sitting under the cherry blossom trees"

photo credits: appareassociazione.blogspot.com

This is the image that could be drawn - certainly the one I see - by observing the ideogram of "sakura". This is far from being the explanation why the kanji 桜 has this specific form, but it lends itself well to such an interpretation. Especially given its present simplified form. Before leaving us, we cannot conclude without a parenthesis on the writing and the cherry tree kanji.

As you can see in the picture above, Sakura's ideogram 桜 is composed on the left of the radical 木 (=tree), on the right of three dashes with the character 女 (=woman) below. The little part in pink, tell the truth: doesn't it really resemble the petals of a flower?

Actually, this part used to be written in a more elaborate way and had nothing to do with the meaning. It was written like this: 櫻. Later on, it underwent a process of simplification, like so many other ideograms in both Japan and China (where they come from). Bearing in mind that ideograms derive from pictograms, let us observe our character in its transition from pictogram to ideogram in the images below.

photo credits: shufam.hao86.com, shufa.m.supfree.net

This was its transition, and then in more modern times it changed exactly as follows: 櫻 🡪 桜 (in China it became 🡪 樱 ). The double 貝貝, which preceded the present three hyphens, indicated "necklace"; while the single 貝 still means "shell". So you see how, by investigating the Chinese etymology, the real historical evolution is revealed. Be careful, however, because the whole right-hand side (i.e. 嬰) of the ideogram 櫻 has reason to be there solely for a phonetic reason. (Not for reasons of meaning, which is also different between Chinese and Japanese). That is, that part has been "put" there to give the pronunciation to the kanji 櫻 as a whole.

But beyond this brief digression, we still like to see it like this: like a little woman under a flowering tree. Right? Since we are dealing with the simplified character today, we can safely indulge in this reading of the kanji which, coincidentally, is very reminiscent of the image of a woman under the blossoming cherry trees. And it certainly helps a lot to remember the ideogram. After all, this flower also recalls femininity. It is no coincidence that Sakura, or the variant Sakurako (桜子or 櫻子), are quite common female names in Japan.

photo credits: pinterest.it